It Starts with Us: An Exploration of Teachers as Self-Directed Leaders

CompetencyWorks Blog

In the second year of a global pandemic, I decided to make a change: I transformed the summative vocabulary quizzes in my 9th grade German class into formative assessments with an emphasis on student reflection and self-assessment. The place of vocabulary quizzes in a competency-based education (CBE) system has been a subject of debate in my world language department since our transition to CBE began in 2015.

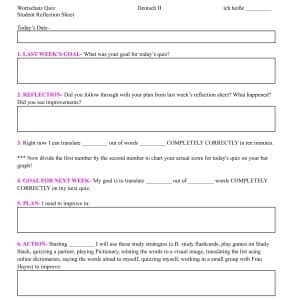

My students predicted their score for their weekly vocabulary quizzes, tracked their actual results in a bar graph, corrected their own work, and completed a reflection sheet where they set a goal for the following week and made a plan for reaching that goal. They were also given class time to fully implement their vocabulary practice plan. As this became a regular part of the class’s routine, I used my reflections on implementation to make adjustments such as supporting students to develop deeper thinking on their reflections, separating the quiz from practice time, and continuing classroom management techniques even as I checked in individually with each student.

The change that I saw was remarkable. Students who had never been motivated to learn their vocabulary before diligently worked to track their scores each week and developed systems for learning that worked for them once they had been given the time to do so. I had always felt that improving students’ self-direction skills was beyond my control as a classroom teacher. However, I was able to do so once I took the initiative to be a self-directed learner myself.

“How Do I Get Started?”

It is not to say that transitions like this are simple. When confronted with all of the current challenges of modern public education–such as not enough subs, reduced prep time, and parent concerns–classroom teachers can feel that they are being asked to pioneer modern methods of CBE with their hands tied behind their back. How can their administrators even ask them to develop student skills in work-study practices (the New Hampshire term for habits of mind) when so many factors are beyond their control? This was a question that I constantly asked myself. Then as I learned more about CBE, I realized that it is not only what is best for students, but that starting small within my own classroom was okay. After beginning work on my Masters of Education, I initiated changes in my own practice starting with vocabulary quizzes.

Classroom teachers should be supported in this work even outside of structures such as graduate programs and can perhaps find an entry point into this work through work-study practices themselves. Self-direction, a key New Hampshire work-study practice, is generally defined as students’ ability to initiate and manage their learning and demonstrate a growth mindset through self-awareness and self-motivation in order to become reflective learners. There is a parallel between how students are applying self-direction in the classroom and how we see their teachers engaged in self-direction themselves (Watkins, Peterson, and Mehta, 2018).

However, many teachers, myself included, have observed a gap between the level of self-direction currently demonstrated by many students and our goals for student self-direction in a functioning CBE system. Teachers can get started addressing this gap using resources such as “Habits of Success: Helping Students Develop Essential Skills for Learning, Work, and Life” by Eliot Levine and the BEST Self-Direction Toolkit. The strategies described here are most effective when embraced by the entire school community and individual teachers have the ability to take positive action as self-directed leaders by initiating this transition with their own students’ self-direction skills. When teachers are supported as reflective and innovative partners, fundamental change becomes even more possible.

“How Do I Model Self-Direction for My Students?”

Innovation and reflection are two leadership traits that classroom teachers will need in order to model self-direction for their students. When teachers take the first step in initiating new practices, they can model risk taking for their students. What is being a risk taker, but initiating new learning and innovating for oneself? Once a classroom teacher has taken that first step to try a new method or activity for supporting student self-direction, they reflect on what occurred in order to improve outcomes in the future.

For New Hampshire teachers, this clearly echoes our goal of supporting students in becoming reflective learners by intentionally developing student self-direction skills through core instructional techniques such as formative assessment practices. In conjunction with these changes made by teachers, districts and school administrations should support a culture of professional growth where classroom teachers have the time, space, and resources to act as self-directed learners.

CBE is a paradigm shift that requires the support of policy, administrative leaders, and teachers in the classroom. While meaningful change will be most effective in a school culture that supports these transitions, teachers can start with small shifts in their own practice. By focusing on innovation and reflection in their own practice, educators become teacher leaders in the shift to CBE as they support students in developing their own agency.

I had always felt that improving students’ self-direction skills was beyond my control as a classroom teacher. However, I was able to do so once I took the initiative to be a self-directed learner myself.

“How Can I Apply This Practically?”

Formative assessment practices provide manageable and practical opportunities for me to continue to innovate in supporting student self-direction skills. When I saw a need to develop a better technique for communicating the whole learning target, I asked my students to reflect on the learning goal, paraphrase the learning goal with a partner, and then asked a student at random to share their understanding of the day’s learning goal with the rest of the class. When made a regular part of my classroom practice, it ensured that every student was involved in clarifying the learning goal for the lesson and supported the development of student reflection skills. The time we spent on this was also a part of academic learning as students practiced their reading competency while they translated the learning goal from German into English.

I also transformed my feedback from corrections into questions. This required students to develop an awareness of their own work and manage the resources that they needed to demonstrate mastery. These are just two examples of powerful shifts that teachers can make in strategies that they’re already using to meaningfully push their work closer to CBE best practices.

“Let’s Do This!”

By modeling self-direction, individual classroom teachers can be the catalyst for improving the same skills in their own students. Teachers are often stretched too thin, but change can start without them reinventing the wheel. When teachers start with small scale prototyping in their own practice, they can help make CBE more accessible for students across their school. Rather than being powerless as I had always feared, we have the ability to begin helping our students become better students within our own classrooms.

Sarah Hayes began teaching German in Concord, New Hampshire in 2016. In this role,  Sarah teaches 7th through12th grade students from the introductory to advanced levels at both Rundlett Middle School and Concord High School (CHS), where she is also an alumna. She also coordinates the German American Partnership Program (GAPP), a student exchange between CHS and Maximilian Kolbe Gymnasium in Wegberg, Germany. In her classroom practice she believes in strong community building, the importance of growth-mindset, and authentic learning opportunities. Sarah is currently working to earn her masters of education in educator practices with a concentration in competency-based education and teacher leadership through Southern New Hampshire University in partnership with the New Hampshire Learning Initiative. She lives with her boyfriend in Goffstown, NH.

Sarah teaches 7th through12th grade students from the introductory to advanced levels at both Rundlett Middle School and Concord High School (CHS), where she is also an alumna. She also coordinates the German American Partnership Program (GAPP), a student exchange between CHS and Maximilian Kolbe Gymnasium in Wegberg, Germany. In her classroom practice she believes in strong community building, the importance of growth-mindset, and authentic learning opportunities. Sarah is currently working to earn her masters of education in educator practices with a concentration in competency-based education and teacher leadership through Southern New Hampshire University in partnership with the New Hampshire Learning Initiative. She lives with her boyfriend in Goffstown, NH.