North Queens Community High School: Blooming the Outcomes

Education Domain Blog

This blog post first appeared on CompetencyWorks on August 2, 2016.

This is the sixth post of my Mastering Mastery-Based Learning in NYC tour. Start with the first post on NYC Big Takeaways and then read about NYC’s Mastery Collaborative, The Young Woman’s Leadership School of Astoria, Flushing International, and KAPPA International.

Imagine my surprise as Lew Gitelman greeted me when we arrived at North Queens Community High School. Pure delight. Twenty years ago, Lew Gitelman, co-founder of Diploma Plus, which has been replicated in many schools across the country, was the first person to patiently walk me through what competency-based education looked like in a school and classroom. After lots of hugs and ear-to-ear grins, we got down to talking about mastery-based education at North Queens, a transfer school serving students who are over-aged and under-credited.

Spanish teacher Martin Howfield opened the conversation with, “We don’t frame learning in terms of passing and failing. We do growth. So mastery-based grading makes sense for our school and our students.” After piloting in two classrooms in the Spring of 2011, they decided to take the whole school to mastery-based learning the next fall. Gitelman, Co-Director of reDesign, has been working with the team to create a system that is aligned to Bloom’s Taxonomy. Principal Winston McCarthy explained, “We use a trajectory of learning based on Bloom’s to move kids to HOTS – higher order thinking skills.”

Blooming the Standards

“You can Bloom the standards. You can Bloom the learning outcomes,” enthused McCarthy. Gitelman expanded on this. “If we want students to be thinking about big ideas and using HOTS, how do we operationalize it?” he asked. “Bloom’s Taxonomy captures the thinking skills students would need and a path to move from lower level to higher level skills. This isn’t just about meeting or exceeding a standard. We want our students to be able to understand the level of thinking they are applying to a problem.”

By aligning around Bloom’s Taxonomy, North Queens is prioritizing students’ development of skills and strategies to solve problems, rather than prioritizing content. The content in each discipline is integrated into skill-building. However, operating in the archaic Regents system that requires students to know about the Byzantine Empire in order to graduate means there are times this doesn’t lead to the voice and choice that is so helpful in motivating and engaging students. (Shame, shame on the New York Regents. It’s time they upgrade their high-stakes assessments to be aligned with learning sciences and adolescent development.)

The grading system at North Queens is aligned with Bloom’s.

Synthesis/Evaluation = Advanced/Mastery

Analysis = Proficient

Application = Capable

Comprehension = Developing

Remember = Emerging

The levels are described in terms of what students can do:

Synthesis is The student solves a problem by putting information together that requires original, creative thinking. The performance tasks might use verbs use as compose, propose, formulate, assemble, construct, or design.

Evaluation is The student makes qualitative and quantitative judgments according to set standards.Performance tasks might use verbs such as estimate, measure, assess, and predict.

Analysis is The student separates information into component parts. The performance tasks include debate, compare, calculate, solve, experiment, and question.

Application is The student solves a problem by using knowledge and appropriate generalization. The performance tasks include illustrate, demonstrate, dramatize, and use.

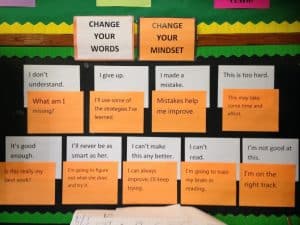

Gitelman reminded us, “When we think about helping students build their skills, we take into consideration their grade level expectations and the level of skills students have reached. You need to meet students where they are.” This doesn’t always mean a student’s lowest performance level, either. Teachers have to make a judgment about where students are academically, how much support they will need and is available, and their ability to tackle challenging material. If they are still recovering from years of failure, bite-sized tasks will help them rebuild their belief in themselves and seed a growth mindset.

Gitelman explained, “Using Bloom’s to focus on the skills is going to lead to better teaching. As they organize units and lessons around learning targets, teachers are able to plan for the different skills they will need to model and how to provide feedback. He continued, “The design of tasks is very important. Ask yourself, within the task itself, is there a path from remember up to synthesis and evaluation?”

It’s very different to help students learn how to critique, synthesize, or evaluate using the content as compared to understanding and remembering content. Many of the schools I visited have described this process of shifting from a stronger focus on content to a focus on skills as teachers having deep conversations about what they expect students to learn how to do and know in each discipline.

Keeping Students Visible

A teacher explained, “In NYC, 55 is a code that tells a student they are failing. When the conversation focuses on how many failures a student is accumulating, they disengage. They disappear.” I was struck by the phrase “disappear” as one of the turning points in the effort to build a policy for multiple pathways to graduation (see Too Big to Be Seen: The Invisible Dropout Problem in Boston and America). When we think about transparency, should we also be thinking about what transparency means for how much we can “see” in our children and teens in school? Can competency-based education help us have a better view of their learning and development?

McCarthy continued, “Our students are coming from years and years of getting 55 or 65. That’s why at North Queens, we focus on growth. We change the conversation. I’m not passing or failing you. I’m giving you opportunities and support to learn. This shifts the responsibility to the students. It’s their education. We talk about growth and next steps. These conversations help us to understand how students are growing and developing.” North Queens uses a framework of emerging, developing, and capable. Students earn credits when they reach capable on seven out of ten learning outcomes in a course.

We saw North Queens’ vision for a highly personalized, highly rigorous model in ELA teacher Joi Walker’s classroom. The walls were covered with inspiration, prompts, learning outcomes, and of course a reference to Bloom’s Taxonomy. Students were all highly engaged, with Walker working closely with students as they needed help.

Meeting Kids Where They Are

“The gap between persistence and resilience is the lack of academic skills.”

Those were more words of wisdom from Lew, “You can’t persist with skills you don’t have yet.” He was describing the absurdity of asking a student in algebra who lacks understanding of numeracy or fractions to persist in solving more advanced problems. “We found that kids will persist if they are actively working on a specific skill that is central or high leverage to moving their learning to the next level,” McCarthy agreed. Gitelman expanded on his point. “We talk about content, but we need to keep the focus on skills,” he said. “It’s easier to ask if a student comprehends the content rather than keep the laser-like focus on skills. They are learning the content through learning the skill. Students should be able to provide evidence that they are building their skills.” Gitelman also added, “The discussion about helping students to build a growth mindset is often framed around soft skills and the emotional side of learning without thinking about the context of academic skills. We think about the growth mindset and building the academic skills together.”

North Queens doesn’t organize around grade levels, especially given that students all have very different credit histories and skills. As McCarthy explained, “There’s a constant tension regarding how heterogeneous or homogenous the groups should be. There is no right answer. We group based on our students’ needs.” Given the focus on skills, North Queens will provide differentiated text for different levels of readers. However, Gitelman warns, “When students are reading at second or third grade, it isn’t possible to master the outcomes. They need to have a basic level of literacy. Similarly, if you don’t teach math conceptually, the students are never going to get traction. We include competencies about building number sense to make sure students have the basics.”

Insights and Inquiry: In creating a competency-based set of policies, we might want to consider additional programming (and funding) for schools to draw on the expertise of literacy and math specialists to help students strengthen their foundational skills. It’s so tragic that a situation has developed where we allow students to just be passed on year after year without helping them learn to read. In a competency-based world, we don’t pass on. We respond. That’s really what accountability is all about.

Lew’s Reading and Resource List

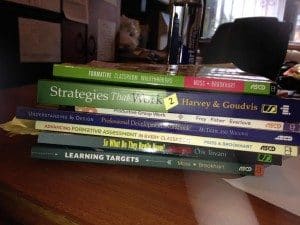

Stacked on McCarthy’s desk were books quite different from those that competency-based education leaders usually recommend to me as must-reads. Described as “Lew’s reading list” I’m sharing the list with you:

Books

- Learning Targets: Helping Students Aim for Understanding in Today’s Lesson by Moss and Brookhart

- Advancing Formative Assessment in Every Classroom by Moss and Brookhart

- How to Assess Higher Order Thinking Skills in Your Classroom by Brookhart

- Strategies That Work by Harvey and Goudvis

- Making Classroom Assessment Work by Davies

- Asking Better Questions by Morgan and Saxton

- Mechanically Inclined by Anderson

- Action Strategies for Deepening Comprehension by Wilhelm

- Teach for Metacognitive Reflection by Fogerty

- So What Do They Really Know? by Tovani

- Classroom Strategies for Interactive Learning by Buehl

Math and ELA

- The Xs and Whys of Algebra by Collins and Dacey

- Fostering Algebraic Thinking by Driscoll

- Comprehension Shouldn’t be Silent by Kelley and Clausen-Grace

- Deeper Reading by Gallagher

- A Handbook of Content Literacy Strategies by Stephens and Brown

- Nonfiction Matters by Harvey

- Subjects Matter by Daniels

- Word Wise and Content Rich by Fisher

- Thinking Through Genre by Lattimer

- Inside Words by Allen

- Metaphors and Analogies by Wormeli

- Building Academic Vocabulary by Marzano

- Craft Lessons: Teaching Writing K-8 by Fletcher

- Nonfiction Craft Lessons by Fletcher

- Teaching Adolescent Writers by Gallagher

Resources

- Framework for Effective Instruction (A Professional Learning Path to Rigorous and Relevant Instruction) by reDesign

- Understanding by Design

McCarthy emphasized that he wished he had read Learning Targets earlier in the journey to mastery-based learning.

Insights and Inquiry: Assessing Proximal Gaps

McCarthy explained that it is important for teachers to spend time at the beginning of the semester in understanding their students – their skills, their maturity, and what engages them. It’s a very wide range in transfer schools, which is why delivering one-size-fits-all curriculum doesn’t work. McCarthy said, “When you become student-centered, this is the central issue that will continue to challenge teachers. Personalization requires greater flexibility, and teachers have to be very comfortable with the discipline, skills, and materials to be able to respond to a new classroom of students. Teachers also need to determine whether they have the skills to provide effective instruction to all the students…and if they don’t, they need to ask for help. One of the ways schools can better meet students where they are is to be honest about the proximal gap.”

Proximal gap? It’s the term McCarthy uses to think about the relationship of the student’s zone of proximal development and how it relates to the teacher’s zone of proximal development. This is a powerful concept in terms of assessing to what degree the school has the capacity to help students – and if they don’t trigger a rapid problem-solving process, to figure out how they can.

Perhaps we should stop advocating for states and districts to spend money on early warning systems for students (an enhancement for traditional schools, but just part of the daily process in highly developed competency-based schools) and think about a warning system to identify proximal gaps in instruction, cultural competency, and coaching social-emotional skills and habits of work.Proximal gap? It’s the term McCarthy uses to think about the relationship of the student’s zone of proximal development and how it relates to the teacher’s zone of proximal development. This is a powerful concept in terms of assessing to what degree the school has the capacity to help students – and if they don’t trigger a rapid problem-solving process, to figure out how they can.

Insights and Inquiry: Solving the Paradox of Transfer Schools

McCarthy described the challenge as the paradox of transfer schools – how to help young people with big, big skill gaps accumulate credits more quickly than other students. (In NYC, you can only earn 12 credits per year, but in transfer schools students can earn up to 18 credits.) How true – I worked in the field of alternative education for twenty years but had never heard it described so well. A paradox.

And paradoxes get you thinking. Is it time to rethink our educational safety net? Should we think about transfer or alternative schools differently so there is a recognition of the tremendous educational jump the students are making and the tremendous breadth of skill-building that teachers must be prepared to support? Building 21 in Philadelphia took a big breakthrough step with the dual approach to credit earning – if you are below grade level and demonstrate growth at a rate of 1.25, you can earn credit or you can earn credit for demonstrating the competencies in a course. Either way provides flexibility for acceleration. It’s just that you don’t penalize students for not having been taught their foundational elementary and middle school skills.

We all know that credits do not equal skills, otherwise there wouldn’t be the huge cost of college remediation. The question is, can we be honest enough to say that skills matter and we should help students in transfer schools (and all high schools, for that matter) build the skills they need to be successful rather than organize around empty credits? There are those who will argue that we should do both – but let’s be honest. It’s nearly impossible to help students build their foundational skills from elementary level to twelfth grade while meeting all the high school credit requirements in two years. If we have to make a choice, I’d argue that we should spend two years helping a student move from fourth grade reading to eighth grade reading, and focus on the discipline-specific skills rather than trying to cover the credits.And paradoxes get you thinking. Is it time to rethink our educational safety net? Should we think about transfer or alternative schools differently so there is a recognition of the tremendous educational jump the students are making and the tremendous breadth of skill-building that teachers must be prepared to support? Building 21 in Philadelphia took a big breakthrough step with the dual approach to credit earning – if you are below grade level and demonstrate growth at a rate of 1.25, you can earn credit or you can earn credit for demonstrating the competencies in a course. Either way provides flexibility for acceleration. It’s just that you don’t penalize students for not having been taught their foundational elementary and middle school skills.

Chugach School District in Alaska can certainly inform us in re-engineering alternative education around highly personalized skill-building.

What’s Next?

North Queens is part of a network run by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching and Learning on school improvement science and the growth mindset. Stay tuned for them to integrate their insights into their school over the coming year.

See also: