What Does It Mean to Meet Students Where They Are?

Education Domain Blog

This post first appeared on CompetencyWorks on June 15, 2017.

This is the twelfth blog in a series for the National Summit on K-12 Competency-Based Education. We are focusing on four key areas: equity, quality, meeting students where they are, and policy. (Learn more about the Summit here.) We released a series of draft papers in early June to begin addressing these issues. This article is adapted from In Search of Efficacy: Defining the Elements of Quality in a Competency-Based Education System. It is important to remember that all of these ideas can be further developed, revised, or combined – the papers are only a starting point for introducing these key issues and driving discussions at the Summit. We would love to hear your comments on which ideas are strong, which are wrong, and how we might be able to advance the field.

At the National Summit on K-12 Competency-Based Education, attendees participated in an in-depth exploration of the relational, pedagogical, and structural dimensions of meeting students where they are. It was organized around three driving questions:

- How do we know where students are?

- What do we do, once we know?

- Which strategies help us navigate systemic constraints?

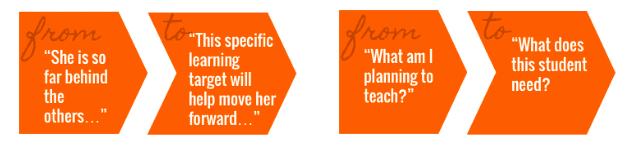

As we move toward the design of second generation competency-based models, there is an opportunity to anchor student learning and achievement in expansive, adaptable, and developmentally ”appropriate” learning and development trajectories informed by the learning sciences. If we are to meet all students where they are, then our commitment must be not only to an uncompromising vision for high achievement – and in practical terms, this means college and career readiness – but also to the daily work of responding to students’ individual needs in a way that fosters optimal growth:

This work is not about meeting the demands of an efficiency-oriented accountability system for its own sake; it’s about ensuring all learners have equitable access to learning opportunities that foster agency and prepare them for life in the world. This is the orientation of learner-centered models, and it is indeed a radical departure from the industrial-age school model that dominates most schools today.

What Does It Mean To Meet Students Where They Are?

At the heart of a mature competency-based learning system lies a fundamental commitment to meet all students where they are. To many practitioners, this sounds equal parts right and radical. Right, because nothing in our lived experience suggests that learners are best served when they are advanced through a system that turns a blind eye to their unmet needs. Radical, because we know it requires that we begin with a commitment to know our students in profound ways – academically, cognitively, culturally, emotionally, linguistically, physically, behaviorally – and not where a grade-based standard or a district-mandated course sequence suggests they should be.

Meeting all students where they are is a commitment that requires that we reconfigure our old systems and practices and paradigms; that we place the individual learner at the center of the learning process; and that the learning process – what actually happens cognitively, neurologically, and developmentally as children learn – be placed at the center of the pedagogical model.

Why this massive redesign of our learning systems? First, the commitment to meet all students where they are is a moral one; we must do this because we now know from decades of cross-disciplinary research that it is the only effective way to optimize learning and growth for all children. This commitment is a pedagogical one; this change must involve a radical shift in our practitioner stance from “teacher” to researcher, designer, diagnostician, and expert facilitator of constructive learning experiences. It’s a political commitment, too. We must do this because we recognize that our country’s economic, political, and civic engines depend upon a strong, adaptive, and capable collective, and that our schools play a central, democratic function toward this end.

Let’s name the elephant in the room: the notion of being on, above, or below “grade level” is an old paradigm that serves, not the learner, but a system designed to efficiently sort and “batch process” students. All students are somewhere on their learning and development trajectory – or multiple trajectories – toward developing the skills, knowledge, and dispositions that are essential for the transition to adulthood. Where each student is, at any moment, on their learning trajectory is just as much a function of their complex needs today as it is about the degree to which those needs have been met in previous years of life and schooling, and in other contexts of learning.

The challenge for all of us is to identify where individual students are on the trajectory, and address their needs, passions, and interests in “real time.” In the traditional education system, most students can only access one small segment of the skills or knowledge of a trajectory at a given moment in time, based on their age: for example, Algebra in eighth or ninth grade, Native American studies in second or third grade, literacy in pre-K through second grade.

There is ample evidence that under these circumstances, the odds are stacked against significant numbers of students being able to access and master what they need when they need it because the learning experiences available to students may – but often do not – fall inside their zone of proximal development (ZPD). For example, the “reading” ZPD for an eleven year old who struggles with decoding is radically different from one who is flying through a Shakespearean play. Yet, they might both be in a sixth grade ELA class which is focused on summarizing a sixth grade text. In this way, their efforts to develop as readers becomes artificially constrained by the classroom learning experiences available to them: neither the student who needs to “reach back” to learn missed skills or content, nor the student who can “reach forward” due to already-mastered skills and knowledge, have access to the support they need within their ZPD.

While this may sound like a familiar refrain, the implications for competency-based models are profound: they underscore the importance of challenging the practice of advancing students based on

- age-based cohorts;

- age-based design of, and access to, learning experiences; and

- age-based benchmarks for performance (such as end-of-year exams, age-based high-stakes tests).

These are artificial constructs designed to serve efficiency and external accountability needs as ends in themselves. As a result, they run at direct cross-purposes to meeting students where they are as students work to master competencies that can be learned at many ages.

The next blog in this series will explore how we know where students are.

Follow this blog series:

Equity

Quality

Learn more: