A Decade On: Lindsay Unified’s Personalized Learning Journey

CompetencyWorks Blog

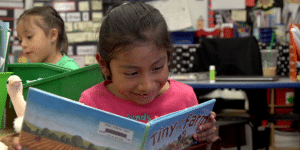

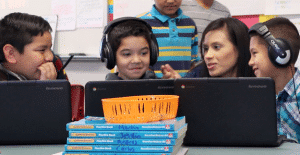

This post originally appeared at Education Week’s Next Gen Learning in Action blog on September 21, 2018. All images are courtesy of Lindsay Unified District.

When educators tell the story of what galvanized them to embrace next gen learning, they often point to a watershed moment, a realization that so fundamentally shifted their thinking that it divided their career into “before” and “after.”

Maybe they were looking at disheartening data around widening opportunity gaps. Maybe they heard the story of a promising graduate who had dropped out of college to take a low-skill, dead-end job. Or maybe they visited an innovative school full of motivated, self-directed, and capable learners and thought, with a twinge, “Why aren’t our students more like that?” Whatever it is, this kind of epiphany inspires people to embark on the long and challenging journey to transform learning and never look back.

To learn more about what a change of this magnitude looks like over the long haul, I spoke to Barry Sommer, Director of Advancement at Lindsay Unified School District, about what prompted him and his colleagues–way back in 2006–to rethink everything they were doing and replace it with a new vision of student learning.

For this edition of Friday Focus: Practitioner’s Guide to Next Gen Learning, Barry shared the story of transforming learning at Lindsay Unified, a small district of about 4,200 students in central California, focusing on:

-

What caused the district to try something so new it didn’t yet have a name

-

How they made the change from a traditional model to a performance-based system

-

Lessons learned and advice to share with the field

A Matter of Time

The district’s eureka moment came in 2006. Barry recalls that he and his colleagues were in Denver, Colorado, at a professional learning event, when it suddenly struck him that “what we are doing is not working. The traditional time-based model is not working. Fourteen percent of Lindsay’s students self-assessed as gang affiliated. We were sending some kids to jail. Academic achievement was as low as it could go. Staff turnover, particularly for teachers, was awful.” It was then that they asked themselves, “Are we ready to do something radically different?”

To answer that question and even more fundamental ones like “Why do we exist?” and “What is a Lindsay graduate?” Barry and other leaders gathered parents, staff, board members, learners, and community members for a series of meetings. “We were starting from scratch. We asked good questions in order to gather enough data to make a plan. We listened to our community, and that became the Lindsay Unified Strategic Design,” which the Board approved and adopted for 2007.

Talking to Barry, it’s clear that Lindsay Unified’s educators saw time as the crux of the problem. They recognized that the traditional sorting of students by age was designed for administrative convenience, not learning. As a result, a new conception of time and mastery of learning became a foundation for the emerging model.

Rather than pushing students through school at a fixed and arbitrary rate, Barry reports, the district embraced a learner-centered, competency-based model they called PBS, or “performance-based system.” According to Barry, thinking flexibly about time affected the learner experience in multiple, positive ways. “The biggest impact has been around culture,” he explains,”which is very hard do in time-based systems because the structures don’t allow it. We broke those down, so learners can take ownership of their learning through goal-setting and spending more or less time as dictated by their needs and interests.”

In practice this means that an English Language Learner can devote more time to working on English Language Arts; “fast runners” in math move on to more advanced content as soon as they are ready; or a learner’s plan to graduate might include spending more than four years in high school.

Learners have agency in Lindsay schools, but they also have responsibility. As Barry puts it, “We message to them that we’re not just going to pass you on. You have to demonstrate mastery of learning to progress, and you can do that independent of your age or grade.” Learners have many options for how they might demonstrate their learning, but these demonstrations are all “verified and validated by the district for rigor,” a step, Barry adds, that is sometimes overlooked in some competency-based models.

New Language for a New Design

Time was not the only obstacle Lindsay Unified tackled on its journey to redesign learning. The language people once used to talk about education also had to be dismantled and replaced with something that aligned with a learner-centered approach. Barry jokes that, in the beginning, “every meeting included a vocab test, as everyone connected to learning, including external stakeholders, made the shift to the new vernacular.”

Barry describes, for example, how Lindsay replaced “student” with the more active learner, along with an accompanying message: “you are a co-constructor of your knowledge.” Teachers became learning facilitators and schools were now referred to as learning communities. Even the term “standards,” a staple of the education landscape, gave way to learning targets. “You are probably noticing that we use the word learning a lot,” Barry says with a chuckle, but “a singular vocabulary leads to a singular vision and way of operating.” Once everyone started using the new language, Barry notes, “all of a sudden learners were at the table whenever we had to make a decision.”

To support learner agency, Lindsay Unified schools also do quite a lot of work around growth mindset and goal-setting. For Barry, this includes “transparency around student data, with charts on the walls where learners monitor their progress.” This practice, he notes, sometimes provokes questions from visiting adults. For example, he recalls a guest asking a boy of about nine, “Is it embarrassing that you are two levels behind in ELA?” to which the boy responded, “Last year I was four levels behind, so soon I’ll be right on track, and I know who’s ahead so I can get help. It doesn’t embarrass me.”

Alluding to the traditional practice of grouping readers, Barry observes, “Kids always know who the robins and bluebirds are. We’re just transparent about it.”

Adults as Learners and Supporters of Learning

Lindsay’s vision for a new kind of learning for students hinges on new kinds of learning for adults. Barry acknowledges that “this work is hard, and a lot of learning facilitators were not prepared to move away from traditional practices like lecturing. We lost 20 percent of staff in five years.” Until about three years ago, he reports, the district continued to offer professional development in traditional ways. That has changed, however. Adult professional learning has become more personalized, with menus of options, project-based learning, virtual learning, and educator-designed experiences. The results, he says, have been very positive, with more stability among staff and a 95 percent satisfaction rate with the new professional learning approach.

In addition, according to Barry, Lindsay puts “a lot of energy into developing classified staff,” the non-teaching adults like bus drivers, secretaries, business professionals, aides, support providers, crossing guards, and cafeteria workers. “These adults tend to live in the district, and they are the first people who see learners each day. Any one of them can articulate what our model is. We all share a singular, aligned, and coherent vision of learners at the center.”

What Lindsay Unified Learned

Today educators at Lindsay Unified can point to plenty of evidence of success: both attendance rates and school climate data put the district at the 99th percentile in their state. “Learners feel connected to everybody,” Barry says. “They feel safe and bonded as a community. Drugs and alcohol are not a significant issue.” The emphasis on “positive culture, not discipline” has also yielded results: suspensions and expulsions are down 65 percent since they instituted the performance-based system.

On the academic side, Barry reports “steady progress over time, from 25 percent proficient or above to 57 percent. Learners are motivated and engaged, and every subgroup is growing.” At the same time, four-year college and university enrollment has doubled during the same time frame, with a very high completion rate (over 70 percent graduate within six years) for Lindsay graduates, many of whom are first-generation college attendees.

Lindsay Unified is also recognized as a thought leader for next gen learning, sharing their expertise through Lindsay Leads, an initiative to provide coaching and consultation to other schools and systems to develop their personalized learning models. Lindsay is also a Partner District within the Transforming Learning Collaborative, a partnership of pioneering schools offering educator-to-educator professional learning, founded by NGLC, Da Vinci Schools, and Schools That Can.

Though Barry is quick to say that Lindsay Unified is still working on making what they call the “Ideal Learning Experience” a reality, with over a decade of learning redesign under their belts, the district is in a position to provide guidance to those just setting out. Here are some of Barry’s recommendations:

“Get meaningful input from all stakeholders before you do any transformational work. That way you get automatic buy-in for when you start to implement. We meet people who are doing great work, but if the parents and community don’t know why, it’s easy to revert to the traditional ways of doing things.”

“Be mindful of using tech as an accelerant. You can’t replace teachers with computers, but it’s really hard to personalize and monitor personalized goals without technology.” An investment in technology can also address issues of equity, he notes. “Only privileged kids had internet access, and we would find the learners who were not connected at home in the morning on the lawn at the District Office using the wireless. We couldn’t get a service provider–they lose money serving our community–so we built our own.” Ninety-nine percent of the district’s families are now connected at no cost to parents. “The whole program is available for learning at all times. That’s how a learner can progress two levels in one year.”

“If we could wind back the clock, we would emphasize SEL (social-emotional learning) way more than we did. Lifelong learning is a push right now, along with figuring out how you embed it into the curriculum and how learners demonstrate proficiency. It would have been better to do that at the start. It was easier to create the academic progressions, but we probably would have grown the academics at the same time if we had been working on these skills right away.”

See also:

- An Interview with Brett Grimm: How Lindsay Unified Serves ELL Students

- An Interview with Principal Jaime Robles, Lindsay High School

- Six Trends at Lindsay Unified School District

Amanda is the Content Manager for Next Generation Learning Challenges.