Aspen Institute Report Provides Powerful Support for Developing Social-Emotional Learning

CompetencyWorks Blog

Advocacy for social-emotional learning (SEL) in schools is growing, and making the case is not difficult on moral and rational grounds alone. After all, who doesn’t think that helping students become motivated, responsible, compassionate, and focused is a good idea? Who doesn’t want to improve equity in schools and provide nurturing relationships for the youth in their communities?

Advocacy for social-emotional learning (SEL) in schools is growing, and making the case is not difficult on moral and rational grounds alone. After all, who doesn’t think that helping students become motivated, responsible, compassionate, and focused is a good idea? Who doesn’t want to improve equity in schools and provide nurturing relationships for the youth in their communities?

But deeply influencing educational policy often requires empirical evidence in addition to moral and rational arguments, and the new Aspen Institute report provides all three. The report, From a Nation at Risk to a Nation at Hope, summarizes findings and recommendations from an extensive study by the National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development.

Their central argument is that “Since all education involves social, emotional, and academic learning, we have but two choices: We can either ignore that fact and accept disappointing results, or address these needs intentionally and well. The promotion of social, emotional, and academic learning is not a shifting educational fad; it is the substance of education itself. It is not a distraction from the ‘real work’ of math and English instruction; it is how instruction can succeed.”

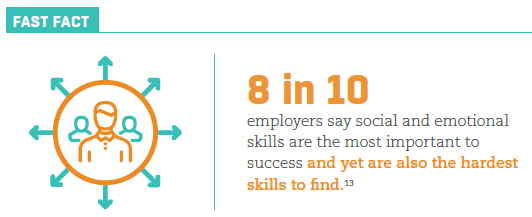

Accompanying the main report, the Commission released a Practice Agenda, a Research Agenda, and a Policy Agenda. Together, these resources provide solid support for why we need social-emotional learning, plus extensive recommendations for advancing the work. The report demonstrates that students, teachers, principals, parents, and employers want this change. Studies they cite, for example, found that “97% of principals believe a larger focus on social and emotional learning will improve students’ academic achievement,” and “nine out of 10 teachers believe social and emotional skills can be taught and benefit students.” They also cite research showing that SEL work “can be undertaken by schools at a reasonable cost relative to benefits.” (I’ll write more about this in an upcoming blog post.)

Impressively, the report shares findings from one of two meta-analyses that combine results across more than 250 studies and show that participating in social-emotional programs improves students’ academic performance. Students also did better on key SEL outcomes, including positive social behaviors, levels of social and emotional skills, conduct problems, emotional distress, and attitudes toward self and others. These findings provide powerful support for implementing SEL programs in schools and out-of-school time programs.

And what does “social-emotional learning” really mean? The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) defines SEL as “the process through which children and adults understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.”

Social-Emotional Learning Advances Equity

The Aspen Institute report provides important support for key tenets of competency-based education. In iNACOL’s Quality Principles for Competency-Based Education, the second principle is “Commit to Equity,” and social-emotional learning is a powerful tool for helping all students succeed. For example, the report argues that students of color and low-income students are more likely to experience punitive discipline practices at school and multiple stressors outside school. SEL strategies that improve school climate and disrupt inequitable practices are therefore more likely to help students from these groups feel safe and supported, build their sense of self-control and self-efficacy, and engage in their educations.

In this sense, fostering social-emotional learning in schools is a key strategy for meeting students where they are. iNACOL’s report by this title notes that when students fall short in key social and emotional skills, it should be seen as a developmental issue, not a failure of attitude or morals. It’s likely to reflect students’ limited access to the nurturing and stimulating conditions that support healthy social-emotional development.

Structure and Politics of Increasing SEL Implementation

Achieving the National Commission’s vision clearly requires making major changes without creating unmanageable burdens on teachers, principals, and other school personnel. The report emphasizes the importance of schools providing teachers with the preparation and ongoing learning needed to change to a more holistic approach to instruction, as well as organizational and policy supports that facilitate and remove barriers to implementation. At the same time, they cite research suggesting that teachers who build their own and their students’ social-emotional skills have lower burnout, higher levels of job satisfaction, and much greater impact on students’ academic success.

Also relevant to achieving their vision, the Aspen Institute report seems to be trying to acknowledge and reframe the political battles that have undermined some other education reform efforts. They argue that the rationale for social-emotional learning in schools is “not ideological at all” and “not another reason for political polarization. It brings together a traditionally conservative emphasis on local control and on the character of all students, and a historically progressive emphasis on the creative and challenging art of teaching and the social and emotional needs of all students, especially those who have experienced the greatest challenges.”

While some may disagree with these characterizations of what is historical and traditional, the Aspen Institute is wise to anticipate and attempt to lessen potential barriers to moving toward important student outcomes. The key point is that integrating social and emotional learning with academic learning is grounded in learning sciences research and supported by key stakeholders across the educational system and spectrum.

See also:

- How Do We Know Where Students Are?

- Aspen Institute / Nation at Hope – landing page for all documents

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.