Diversifying the Student Body and Personalizing Student Schedules at NYC iSchool

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the second post in a series about the Mastery Collaborative in New York City. Links to the other posts can be found at the end of this article.

NYC iSchool in the Soho neighborhood of Manhattan is one of the Mastery Collaborative’s eight “Living Lab Schools” that serve as models in New York City and beyond. The iSchool emphasizes that it “is designed to offer students opportunities to engage in meaningful work that has relevance to them and the world, [and] choice and responsibility in determining their high school experience.” Two areas in which the school has developed strong practices related to competency-based education are creating a diverse student body against headwinds of the selective schools process and enabling students to select courses based on their interests.

Deliberate Steps to Recruit a Diverse Student Body

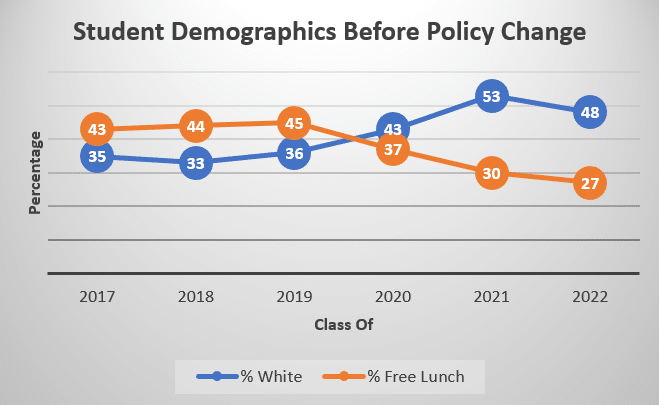

As NYC iSchool developed a strong reputation during its early years, its applicant pool grew and its student body became less representative of the school district, as shown in the figure below. Students eligible for free or reduced price lunch fell from 43% to 27% (compared to 74% district-wide) and the percentage of white students increased from 35% to 48% (compared to 15% in the district). (The two groups overlap, because some white students are from low-income families.)

These disparities were inconsistent with the iSchool’s goals to disrupt systemic inequities and serve a representative student body. They responded by taking advantage of a city policy to help them reach this goal.

These disparities were inconsistent with the iSchool’s goals to disrupt systemic inequities and serve a representative student body. They responded by taking advantage of a city policy to help them reach this goal.

The disparities were likely a result of both district and iSchool recruitment processes. With more than 400 high schools in New York City, applying can be bewildering. Students need to submit a ranked list of up to 12 choices, taking into account their odds of admission at the many “Specialized” and “Screened” high schools. Doing this systematically requires considerable research and often involves multiple school visits and supplemental application components. It has much in common with selective college admissions, but for 8th graders.

NYC iSchool is a screened school, and their admissions rubric considers 8th-grade GPA, ELA and math test scores, attendance, lateness, and the applicant’s score on a required online activity. The activity is intended to help the Admissions committee “think about which students will do well at the iSchool. Those who really strive to be independent learners are those who will be happiest at the iSchool because they understand that the school is consciously moving them toward that goal, and appreciate that the reward will be greater independence in determining their academic path. It is also important to the school that students know what they’re getting into—a high school that is offering a different instructional model. A demonstrated understanding of what that is and a genuine interest in being part of it are qualities that reveal to the admissions committee a good match.”

With the hurdles of finding the right school and completing ancillary activities, it’s not surprising that students from higher-income families, who often have more time and knowledge about navigating educational systems, began applying at a higher rate. To work toward recruiting a more representative student body, the iSchool applied and was approved to participate in the city’s Diversity in Admissions Pilot, which the mayor’s office created to improve equity and inclusion in the school district. This will permit the iSchool to give priority to students who are eligible for free or reduced lunch for up to 60% of their seats in the Class of 2023 and beyond—more than double the 27% in the class of 2022.

This type of effort by the city and the iSchool to move toward structural equity is central to quality in competency-based education. It’s a great example of the city making it possible to dismantle structural inequities, and the school making strong efforts to make use of that opportunity. Clearly it’s an example that other school districts could investigate and emulate.

Two caveats are worth noting. First, the terms of the pilot seem likely to yield greater socioeconomic equity but do not guarantee greater racial/ethnic diversity. Second, the issue remains of whether schools with selective admissions criteria are equitable at all. For example, commenting on the recent Equity and Excellence for All report on the differences between selective and nonselective public high schools in Boston, a reviewer concluded that “The study laid bare an uncomfortable truth that better-off Boston families all recognize—and are largely helped by: The city effectively operates two separate public high school systems, one that puts most students on track toward college success, while the other falls far short of that.”

“No Two Kids Have the Same Schedule”

The iSchool was proud to share that each of their 460 students takes a different set of courses. This emerges from the school’s intention for students to be exercise choice and have responsibiity in their education, and also so they “can get what they need when they need it.”

Student schedules include core classes, online learning, challenge-based modules, and advisory:

- Core classes – These include state-mandated courses such as math, English language arts, and science, but also school requirements such as a critical thinking class in an area related to the student’s interest that includes a research project. The school attempts to tailor some of the courses to student interests and experiences, such as an 11th-grade ELA course focusing on the immigrant experience and a chemistry course focusing on the science of sweets.

- Online classes – To prepare for the required New York State Regents exams in US History, Global History, and Biology/Living Environment, students take online courses with teacher support and are expected to spend three hours per week working on these courses at home.

- Challenge-based modules – These quarter-long courses based on student interests and include authentic topics and projects. For example, students in a music module develop an original composition which during the final week is played by a visiting professional string quartet. Also, “Pop-up Restaurant” is an economics module that challenges students to operate a one-night-only restaurant that raises funds for the parents association.

- Advisory meets three times per week, once for 45 minutes and twice for 15 minutes, with a common curriculum across advisories and a different theme for each grade level. Unlike most iSchool classes, which have students from multiple grade levels, advisory is single-grade and students stay with the same teacher for all four years of high school.

To accommodate student course preferences and 460 different schedules, scheduling is complex and time-consuming. Teachers decide on their challenged-based modules in spring of the previous school year, taking into account what academic disciplines need to be covered. These are combined with the other course types to create a master schedule, which is then converted into a set of Google Forms on which each student indicates three choices for each class period. Faculty ensure that each student’s choices meet their needed credits for progress toward graduation, as well as IEP requirements. With those requirements in mind, a final schedule is produced for each student.

Student Voices

During a student panel and classroom visits, students said they feel more motivated at the iSchool than in previous schools because they get to choose their classes, the work is more hands-on, and it’s more focused on skills rather than memorization. They liked that they receive mastery assignments with a rubric at the outset, so they know what they need to do.

Students pointed out that “We do have tests to make sure we’re mastering the materials, and if you don’t demonstrate mastery you have to go back and do more.” One student said that the most challenging part of being at the iSchool after attending a non-mastery-based middle school is that “Things don’t just go away if you don’t do them. You actually have to do everything, like retaking a test you failed,” although “you can always get the highest grade, no matter how long it takes.”

A student explained that if you don’t finish something and the class moves on, you need to arrange with the teacher to come before or after school or during lunch for extra help. She added, “If you don’t take that initiative, you won’t pass. That’s real life—people aren’t going to chase you.” Teachers later explained that variable pacing and opportunities for support, revision, and going into greater depth are also part of the day-to-day class periods. In other words, students do have responsibility for making up competencies on which they have not demonstrated mastery within a particular time frame, but the structure and flow of class periods also provide those opportunities.

We are grateful to the NYC iSchool staff and students who hosted our visit, served on panels, and invited us into their classrooms. The faculty panel included principal Isora Bailey, assistant principal Michelle Leimsider, and teachers Evelyn Baracaldo, Kristen Brown, Katherine Coughlin, and Brittney Klimowicz.

Other posts in the series:

- The Mastery Collaborative: Dozens of NYC Schools Support Each Other’s Reforms

- Mastery-Based Making: The Urban Assembly Maker Academy

- What’s College Like for Students from Mastery-Based High Schools?

- Project Example: Mobile App Design at Urban Assembly Maker Academy

See also:

- Amplifying Messages on Equity and Anti-Racism from SXSW EDU

- Quality Principles for Competency-Based Education

- Designing for Equity: Leveraging Competency-Based Education to Ensure All Students Succeed

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.