In Reflection: Eight Lessons Learned Over the Past Decade

CompetencyWorks Blog

This article is the second in a three-part series of my final reflections on the field of competency-based education before I depart CompetencyWorks. You can find more about how to move from traditional to modern schools, including a series on what it means to modernize your schools to include competency education, at LearningEdge.

This article is the second in a three-part series of my final reflections on the field of competency-based education before I depart CompetencyWorks. You can find more about how to move from traditional to modern schools, including a series on what it means to modernize your schools to include competency education, at LearningEdge.

I feel like I’ve been in “the zone” for eight years. Honestly, I’ve been in the flow that is just as exciting as the crazy high of swimming among 30 whale sharks in the Yucatan. Constantly learning, readjusting the internal framework I use to cluster ideas, checking out new insights to work out whether they are partial, conditional, nuanced, or something that holds generally true. Below are just a few of the big A-HA!s I’ve had over the years. What insights and lessons learned have you had in your work? Wanna share? We all benefit by hearing from each other.

1. Student Agency is Much More Than Voice and Choice

When I was first introduced to the idea of student agency, it was described to me as voice and choice. And that is how I described it for years. But now I know that more choice isn’t the same as more agency. In fact, too much choice can be detrimental to learning if it requires students to use working memory to navigate their choices. Voice was interpreted in multiple ways: sometimes about leadership and creating roles in governance in schools, sometimes referring to aspects of cultural responsiveness, sometimes about adolescent and identity development, and sometimes just as another word for choice.

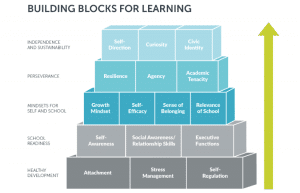

I knew there had to be more but wasn’t familiar with the research. Thankfully, Students at the Center’s Motivation, Engagement, and Student Voice put me on a path toward a deeper understanding. Then I discovered Building Blocks for Learning, and an entirely new understanding of what it means to help students become lifelong learners came alive.

How do you explain what student agency is, and what are you putting into place so students are able to take more ownership of their education?

2. Student Agency and the Building Blocks for Learning are a Game-Changer

As I developed a deeper understanding of student agency — what it means when students have purpose so they are motivated, engaged, and possess the skills and mindsets to learn — I started to see that it was the spark of a virtuous cycle. The more students are active learners and putting forth effort, the more they are taking responsibility for the learning, and the more teachers can direct their attention to the points when students need guidance. Furthermore, the more we invest in the Building Blocks, the more students become lifelong learners. Isn’t that amazing? Invest in coaching students in the Building Blocks for Learning, and students will be better learners, the system works better, teachers can differentiate learning and be more responsive in the classroom, AND we are going to help every student be a lifelong learner. So cool!

Now, compare it to the traditional system that can easily fall into a vicious cycle of compliance, exclusion, lowering expectations, and mistrust. Teachers deliver curriculum, some students get it and some students don’t, and just about everyone is passed on regardless of what they learned. Those on the margins are bored silly and may be pretty angry that they aren’t being challenged in meaningful ways. Trust is crumbling. Students may act up and be sent out of the classroom, and, if they are a student of color, they may be excluded from school altogether. The message is you don’t belong. Students disengage, putting in less and less effort.

Foundational and outcome-producing, the capacity to support students in developing the Building Blocks for Learning is a non-negotiable. What have you or what are you putting into place to ensure that your teachers have the support and conditions to help each and every student develop the Building Blocks?

3. Shared Vision, Shared Understanding of Learning

In the early implementation districts (documented in the a-bit-out-of-date Implementation Insights), almost all of them took the time to create a shared vision with members of the community. This provided the opportunity to look at the”‘why” behind wanting to modernize schools, created a robust definition of student success that could be translated into a graduate profile, and built a foundation of public will and local leaders that could speak to why schools were changing. Some of the districts also created guiding principles that engaged everyone in thinking about what effective instruction and assessment looked like to reach the graduate profiles. However, as more and more entry points have emerged, the worry is that changes are being introduced in small steps but leaving the beliefs and pedagogy of the traditional system in place.

The lesson learned, first shared with me during my visit to Windsor Locks School District, is that it helps immeasurably when schools and districts take the time to build a shared understanding of how children (and adults) learn. The research on learning needs to be one of the primary drivers in designing schools and learning experiences.

Once upon a time, we had to dive deep into academic journals to learn about the research on learning. Now it’s being translated into forms that are more accessible to educators. You still have to stay alert about whether organizations are promoting cognitive, psychological, or a combination of both types of research on learning. (Read Amelia Peterson’s article to understand these two camps.) You can read high level summaries of the research on learning from these resources: CompetencyWorks’ 10 Cornerstones, Transcend’s Designing for Learning, and OECD’s summary of research and practitioner guide.

How would you describe your district and school’s guiding or shared pedagogical principles?

4. Instructional Support is the Variable, Not Just Time

Who would have guessed that using the memorable phrase “time is a variable and learning is a constant” to compare competency-based learning to the traditional system where “time is a constant and learning is a variable” was going to be such a serious misstep? It’s such a powerful phrase to emphasize the time-based and variable nature of the traditional system. Think about it. The As and Bs and high GPAs can’t mean much when even valedictorians may discover that they have to take remediation classes when they get to college. Wonder why we have ACT and SAT? It’s because course credits are not reliable ways to determine what students know. Learning as a constant should have been pushing us toward moderation and calibration to help reduce variability. But it didn’t.

What did happen is that it “time is a variable” was reduced to self-pacing. Why would our understanding go there but not to moderation? I think the ideas that students are empty vessels just waiting to be filled up with knowledge means that the image of students sitting compliantly in rows is quickly replaced with the image of students sitting compliantly in front of a computer. However, that shouldn’t be happening in competency-based schools because students are active learners. CBE schools should be trying to engage and motivate students so that they are putting in the effort required to learn. Students may be using digital educational products as an option for instruction, practice, and rapid feedback, but these products are supplemental. Computers should be used as a tool to organize the resources for learning experiences and similarly as adults for productivity.

It’s also possible that the traditional and antiquated idea of intelligence as fixed and the belief that educators know which students can learn to high levels (and which can’t) is causing us to think that “time is a variable” jumps to the image of some students as fast learners and others as slow. “Time as a variable” could easily have been interpreted as increased responsiveness such as variable or differentiated amounts of instructional support. This is an example of how the beliefs underlying the traditional system can can eat away at personalized, competency education when it isn’t intentionally and systematically challenged.

All of us — policymakers, experts, educational leaders, and teachers — have to constantly work hard to fully eradicate this belief. It may even be unconscious, just sitting there as a bias that flashes by so quickly we don’t even know that it is shaping opinions and decisions. I know I’ve experienced it. I’m talking to a student and suddenly they say something that is profoundly insightful and I notice that I’m surprised. And hidden behind that surprise was the assumption, the bias, that the student wasn’t going to say something profoundly insightful. That’s bias.

If you really don’t believe some students can learn something and you are confident in your ability to know which ones aren’t going to learn, it’s pretty easy to jump to why bother? If you believe that there are always going to be students in your school who aren’t going to be successful, then it makes sense to provide scaffolds to access curriculum without taking the time to repair gaps that would allow them to master the material. “Time is a variable and learning is a constant” gets reduced to self-paced because there is a belief dragging down our expectations that some students are always going to be behind. Thus, instead of working together to figure out how to engage and motivate students who need more help and provide the best instructional interventions to them, we simply accept that some students are slower and less intelligent. And there lies the crux of the accountability problem. Holding ourselves accountable starts with sharing the idea that all of us involved in education — especially districts, schools, and teachers — can learn enough and become effective in our jobs so that every student is soaring.

One trick I’ve used to help me challenge the old beliefs is to get a really clear picture of everyone at a different point on the continuum of learning, with students at different points in different domains. Replace the straight line trajectory of one-size-fits all curriculum and pacing guide with a scatter plot that shows students at different points. I try to remember that learning itself isn’t exactly the same on a day-to-day basis: some students may be going deeper, some may be making more connections and finding more relevance, and some are learning more than others because they are repairing gaps and building fluency where they once were weak along the way.

What I’ve learned is that it all comes down to celebrating growth and achievement levels. Don’t let anyone force you into choosing. It’s both/and.

To what degree have you put into place the systems, support, instruction and assessing capacity to ensure that learning is a constant? (You may want to check out Quality Principle #9 Responsiveness and Principle #11 Consistency and Reliability.)

5. Making the Transition to Competency-Based Education Requires Attention to Culture and Pedagogy

I’ve written about this a fair amount so I won’t go on and on. Suffice it to say, we made a serious misstep when we started talking about competency-based education to only emphasize the structural changes. We thought we needed to do that to help people understand. But what we saw was a lot of districts and schools only making the structural changes without attending to the underlying belief systems or updating pedagogy to be more aligned with what we know about how students learn. We made a mid-course correction when we produced Quality Principles for Competency-Based Education. Not only do we emphasize culture, pedagogy, and structure, but we lead with culture and pedagogy.

The research on learning is now being summarized and distributed with some integration across the separate fields of cognitive sciences and psychology so it can be accessible to practitioners. We are definitely entering a new stage where every district and school can create shared principles of pedagogy to guide instruction, assessment, and professional learning.

There’s been a bit of a debate in the field about whether the culture of high quality schools is the same for competency-based schools as it is for any school. I ended up skimming a lot of the research on what makes an effective culture for high-achieving schools. My conclusion is that there is in fact a different culture needed for competency-based schools.

The main difference is that many reports referred to aspects of orderliness and compliance. If you’ve read the research on racial disproportionality of suspension and exclusion, a lot of it is about behavior and non-compliance. One book described having safe schools by having relationships with the police. Now, hold on there. That’s not safety if you are an African-American boy or young man. The culture of inclusivity and belonging is about creating safety, respect, and trust. I think one can also argue that the culture of empowerment that enables responsiveness is also different than a focus on delivering curriculum with fidelity. One is student-centered; the other curriculum centered. Yes, high quality curriculum makes a difference, but not if it feels like one more form of compliance to a student. Let’s make sure we have curriculum that makes a difference within cultures and pedagogy that draws on cultural responsiveness and student-centeredness.

What do you have in place for each of the quality principles outlined in Quality Principles of Competency-Based Education? What is need in terms of culture, pedagogy, and structure to put the ten distinguishing features of competency education into place?

6. Carrots are Better than Sticks for Engaging Districts and Schools (and Educators) in the Transition to CBE

Making the transition to competency-based education is more difficult than adding a new program. It’s more difficult than changing from one instructional model to another. Why? Because it’s systemic, in that once you start to change something, you are going to find that other things need to be realigned. It’s also a second-order change, which means the underlying beliefs and ultimate purpose are different. Changing the driving purpose from delivering the same curriculum to everyone is very different from ensuring that all students are learning, making progress, and getting the supports to have the academic knowledge and skills needed for college and career, the ability to apply that knowledge, and the know-how to be a lifelong learner.

We’ve learned that requiring districts to change is risky. Those schools that don’t want to change, for whatever reason, are going to do minimal amounts. They are going to most likely either approach it programmatically or as a change in a few practices. Because that’s what districts and their leaders know what to do. The problem is that students do not benefit, and people around the state start thinking the handful of changed practices is all that competency-based education about. We can always change the name…but the fact of the matter is that it is going to be better for us at this stage to have fewer high quality districts than it is to have it be widespread without generating any additional benefits for students.

It’s just plain difficult to require people to change and nearly impossible to force them to change their beliefs. In fact, compliance likely triggers a non-learning stance. Just tell me what you want me to do. Competency-based education is about creating a learning organization where people share a vision that’s strong enough to make it worth taking risks. A compliance approach and a compliance mentality are just not going to get us there.

We need to explore more ways to create opportunities, provide support, and make it very cool to want to be competency-based. Maybe you even have to apply to be certified as competency-based? In general, I believe in inclusiveness, but what if being certified as competency-based meant a reduction in regulations? What if it gave schools more autonomy?

How are you using carrots to engage people in your team, schools in your district, or districts in your state to consider taking steps toward modernizing their instruction and design?

7. Beware When Policy Outstrips Practice

Policy to provide or catalyze competency education is proving much easier to introduce than it is to transition to competency-based education. At CompetencyWorks, we wanted policy to be informed by practice. There’s a risk when we introduce more enabling policy without the the knowledge and supports to go to scale. We’ve learned so much over the last decade — if only we could have a do-over and build on today’s knowledge of how deep personalized and competency-based education go together. However, we don’t have all the answers yet, and we need to tap into knowledge from outside the competency-based education field to ensure we are drawing on the very best that is aligned with the research on learning.

How can we improve our capacity to develop and document high quality models? Some argue that what we need is a variety of models with specific practices to go to scale. Others argue that the beliefs and culture need to change if we are going to create high quality, sustainable models. Others say to start with the research on learning to create the capacity to drive decision-making on decisions tiny and big. All agree that we need to make the transition and implementation easier. The lesson learned is to consider policy as more than setting directions and defining the rules in which schools operate. It’s equally about creating the conditions and the systems of support to fully assist districts in the transition.

What is in place in your state to support districts and schools learning about personalized, competency-based education? How might you create opportunities for learning that build trust and networks while pushing for deep understanding and a commitment to high quality implementation?

8. Don’t Introduce Grading Changes Until You Have Enough of the System in Place so Students and Teachers are Willing to Testify that CBE Produces Benefits

Too many districts and schools think competency education is primarily a change in grading. National organizations that promote that idea as the first or second bullet in describing competency-based education add to the confusion. (CompetencyWorks definitely contributed to the confusion by writing an early paper on grading in the hope of responding to questions…but we should have realized the message we were sending out. Seriously, why mention grading at all? Why not say, operational practices are aligned with the research on learning and are designed to motivate and engage students to put their best effort forward toward reaching learning targets?)

There are a number of pieces that need to be in place before any significant changes in grading can occur. First, if you are going to separate academics from behavior so that scores help students understand where they are in terms of grading, you’d better also have a way of helping students understand what behaviors are related to learning and opportunity for reflection, feedback, coaching, and opportunities to try, try again. Second, the learning targets need to be explicit. Students need to know what proficiency looks like and this needs to be consistently held across the school. Consistency requires moderation among teachers. Finally, the school needs to be responsive. It need to organize itself so that it can offer timely and differentiated supports. Lunchtime or expecting teachers to provide all the supports for their students is not sustainable (and most likely to result in inequity issues). Students with gaps are going to need more instructional support, and all students are going to need a little extra help at times, which means the organization has to be flexible to provide opportunities for students (and adults) to keep learning, practicing, and demonstrating their learning. Don’t change grading until you’ve got the “not yet” mentality alive and well in your school.

What are practices in your school that are aligned with “not yet”? Which ones aren’t?

Read the Entire Series: