Learner-Centered Tip of the Week: Dodging the Digital Poster

CompetencyWorks Blog

This week’s tip comes from Seth Mitchell, a technology integration coach in the Monmouth schools in RSU 2. This post originally appeared at the Learner Centered Practices Blog on January 16, 2018.

Because I completed much of my K-12 student career before school computers were used for much besides word processors, my digital options for sharing learning were quite limited. When I had the opportunity to select my own project product, I often found myself relying on the old school standby: the poster.

As a reasonably successful student, I could complete a poster project without too much effort, and I knew I could get an A+ by relying on presentation: using pictures, penciling everything neatly before outlining in marker, aligning everything with a ruler, and so on. To be honest, I don’t remember much about the content of the posters I made, largely because I don’t think that was my focus. I do recall the process of closely paraphrasing from encyclopedias and library books to grab the necessary facts I was supposed to include, but that required more of my thesaurus than my brain.

I suspect my experiences are not unique. Readers of a certain age will probably recall similar projects from their memories of school. Times have changed, both pedagogically and technologically, and kids generally don’t need to ask their parents to buy stacks of poster board in bulk. Many learners now turn to laptops and mobile devices when it is time to demonstrate understanding of new concepts and content, and the poster project has been replaced with slide shows, movies, and Google docs.

But a digital poster project is still my old poster project in essence.

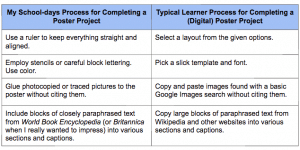

Appearing on a screen instead of card stock doesn’t change the nature of the information presented, so as educators, we need to be careful of simply replacing the superficiality of the traditional poster with a technological equivalent. In our eagerness to integrate technology into the learning process, we can confuse digital flash with depth, and we can fall into the trap of allowing students to disguise shallow thinking with a glossy finish. As we provide opportunities for learners to select their own means of proving evidence toward targets, we can inadvertently open the gate to the easy way out. With the best of intentions, we can even celebrate work that looks nice but required little of the learner. I don’t have to leap to find parallels between the poster projects I created as a kid and their contemporary counterparts:

In both cases, depth of content learning is likely minimal. Actually, the digital poster — be it slide show, website, or [insert technology here] — probably requires less effort than its predecessor.

To discourage the poster-assembly mindset, we can run through a brief checklist of antidotes when we plan learning tasks. Are we asking learners to produce work

- that can’t be found via Google in a minute or two?

- that is true to the medium? (Are the products similar in any way to those we’d find people creating in the actual workforce?)

- for an audience beyond the classroom?

- for a purpose beyond the assessment score?

In the end, we will get precisely what we ask for, so we need to make sure we ask for the right thinking and doing.

—

In my next post, I’ll continue this train of thought and explore what it means when we ask learners to be thoughtful producers of content when they have myriad possibilities in an environment characterized by voice and choice.

See also:

- Learner-Centered Tip of the Week: Four Tips for Crafting Driving Questions

- Learner-Centered Tip of the Week: Giving Learners MORE Voice

- Learner-Centered Tip of the Week: Including Multiple Readiness Levels

Seth Mitchell is a technology integration coach in the Monmouth schools in RSU 2. A Southern Maine Writing Project teacher-consultant and former high school English teacher, he enjoys collaborating with other educators to design teaching and learning experiences.