Making Sense (or Trying to) of Competencies, Standards and the Structures of Learning

CompetencyWorks Blog

States, districts, and schools are developing a range of different ways to structure their Instruction and Assessment system (the set of learning goals of what schools want students to know and be able to do; the way they can identify if students have learned them; and, if not, how they can provide feedback to help them learn it). I’m having difficulty being able to describe the differences as well as the implications. The issue of the importance of the design of how we describe what students should and/or have learned has come up in meetings about assessment, about learning progressions (instructional strategies that are based on how students learn and are designed to help them move from one concept to the next), and with the NCAA over the past month.

So I’m doing the only thing I know how to do—which is to try to identify the different issues or characteristics that are raised to see if I can make some sense of it. For example, here are a number of questions that help me understand the qualities of any set of standards and competencies:

Is it designed to reach deeper levels of learning?

Some structures clearly integrate deeper learning and higher order skills, whereas others seem to depend solely on the level of knowledge based on how the standard is written. We could just use standards and forgo an overarching set of competencies. However, the competencies ask us to ensure that students can transfer their learning to new situations. It drives us toward deeper learning.

Is it meaningful for teachers for teaching and for students for learning?

As I understand it, much of the Common Core State Standards was developed by backward planning, or backing out of what we wanted kids to know and be able to do upon graduation and then figuring out what it would look like at younger ages. Much less attention was spent on structuring the standards based on how students learn and meaningful ways to get them there. The learning progression experts are emphatic that it is important to organize the units of learning in a way that is rooted in the discipline and helps teachers to recognize where students’ understanding is and how they can help them tackle the next concept. That means the structures are going to be different in different disciplines. Thus, we need to understand how helpful the structures of the standards, competencies, and assessments are to actually help students learn.

What are the implications for assessment?

There are a number of considerations regarding assessment. First, we want to make sure that the standards and competencies are organized to create a powerful feedback loop. Second, we want part of the assessment system to help us to double check that students learned something. Regardless of if we are assessing each student or doing quality control on whether teachers are determining proficiency in a consistent way, we expect students to be able to transfer their learning—thus we are going to look toward performance-based assessments. Which brings us back to how the structure is organized. To what degree is the granularity and organization going to support instruction at the higher levels of learning?

Is it user-friendly?

Certainly the language of the standards and competencies needs to be written in a way that engages students. Many schools are using “I can…” statements. However, we should also think about the overall structure as well. Too many standards, and it starts to feel like a checklist.

What are implications for creating interdisciplinary and project-based learning?

Interdisciplinary projects are one of the best ways to fully engage students, as is robust project-based learning. If the standards are too granular, it’s hard to figure out how they are connecting to the overall project.

What are the implications for tracking student progress and communicating what students know and are able to do?

Students who have experienced a lot of failure in school will want to be able to see their progress, leading us to smaller chunks of learning. However, chunks that are too small can lead to a linear approach to structuring learning. By the time we start thinking about communicating to other schools and colleges, we want broader ways to communicate what students know and are able to do—whether using a course as a proxy or a form of standards-based transcript.

I get a bit dizzy trying to think this through (and I’m sure I don’t have all the considerations identified). I think it is going to require a group process to tackle this challenge, drawing upon different types of expertise, including the student perspective, to extract the characteristics and implications of different structures.

However, we can start looking at the different ways districts and schools are structuring Instruction and Assessment. Below are examples. (FYI, they’ve been pulled together because they are available on the web, not as examplars. They may also not be up to date as districts tend to continue to try to improve them periodically.)

- RSU2 and many of the districts that have been trained by the Reinventing Schools Coalition have organized measurement topics and learning objectives. As I understand it, assessment is focused on the measurement topic and is used to determine if students have reached proficiency.

- New Hampshire has developed a competency statement validation rubric, graduation competencies, work study competencies, and examples of course level competencies.

- Here is another example, this one geometry, from Lindsay Unified School District.

- Building 21 uses large competencies to structure the goals of learning. For example, their math graduation requirements include five big learning expectations for students.

- Sanborn Regional High School uses competencies to organize the big ideas (based on NH’s state competencies). There are seven core competencies for Algebra 1 (taught to incoming 9th graders).

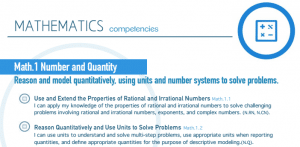

- Competency 1: Numbers and Quantity: Students will demonstrate the ability to use and extend properties of the real number system and analyze and represent problems by their quantities.

- Competency 2: Algebra: Students will demonstrate the ability to analyze structure in expressions and solve problems when applying the concepts of polynomials.

- Competency 3: Algebra: Students will demonstrate the ability to synthesize mathematical concepts, properties and skills to create equations and use them to solve real world problems.

- Competency 4: Algebra: Students will demonstrate the ability to analyze and apply concepts of equations, inequalities and systems to solve real world problems.

- Competency 5: Functions: Students will demonstrate the ability to interpret and build functions.

- Competency 6: Functions: Students will demonstrate the ability to construct and analyze linear, quadratic and exponential models.

- Competency 7: Probability and Statistics: Students will demonstrate the ability to interpret categorical and quantitative data.

- Maker Academy, a brand new school in New York City, has constructed five levels to show how a student is moving toward proficiency (and beyond) for all of their content areas, including design thinking.

- Great Schools Partnership recommends creating a structure with four levels, each with a different method of assessment. I’d love to see examples from a school that has embraced this model so we can add it to our list of examples.

Once I started looking at these different structures, I quickly jumped to a deep appreciation for how important calibration is for different academic levels and how important it is that our educators possess this knowledge. Because if they don’t know what proficiency looks like, how can they help students reach it? Furthermore, if we can’t rely on teachers to be able to credential student learning in a way that is credible, it’s going to be very hard to unstick ourselves from the NCLB top-down accountability system.

One more thing before I finish. We can’t leave out all those so skills that we know are important to learning and success as an adult which has been labeled with the messy term, “non-cognitive skills.” (See Andy Caulkins It’s Time to Trash the Term Non-Cog and Soft Skills) We should take a look at how districts and schools are constructing those and the implications thereof. In most cases, I’ve seen lists of desired behaviors, but not systems to engage with students about those behaviors. I don’t have a lot of examples at my fingertips, but here are a few:

- Making Community Connections Charter School has a robust sets of habits of mind and work with very detailed rubrics.

- Building 21 has five Habits of Success.

- Lindsay Unified has a set of lifelong learning standards and uses a simple rubric to engage students in reflection.

|

Score |

What the Learner Does |

|

4 |

The learner always or nearly always demonstrates these characteristics. |

|

3 |

The learner usually demonstrates these characteristics. |

|

2 |

The learner sometimes demonstrates these characteristics. |

|

1 |

The learner rarely or never demonstrates these characteristics. |

As you look at these different types of structures, what jumps out at you? Are there qualities, characteristics, or implications that are important for us to consider?

If you have a model that isn’t represented here, please let us know. We can link to your website or, if it isn’t up on the web, we can add it to our wiki. We want to make sure we have examples of all the different ways people are organizing their learning continuum.

Thanks everyone!