Mixed Signals from Report Cards: Learning Heroes Report Highlights Why Competency-Based Grading Matters

CompetencyWorks Blog

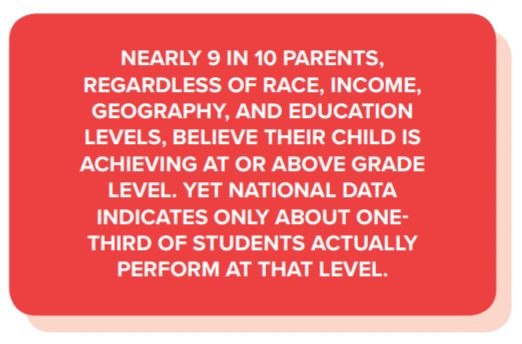

A recent report from Learning Heroes provides a dramatic illustration of the need for schools to transition to more transparent grading practices, such as those in a competency-based education system. The report found that, for three years in a row, a very large percentage of parents in a nationally representative sample have overestimated how well their children were doing in reading and math.

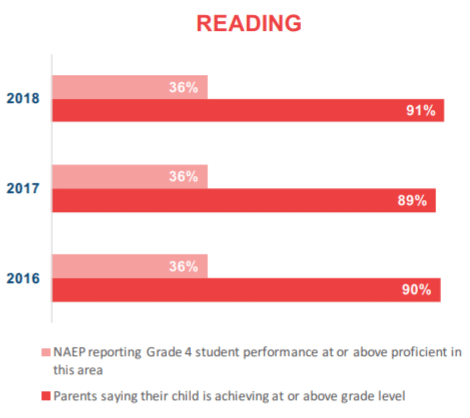

The bar chart below illustrates this stark disconnect for reading. (The math results were similar.) In 2018, for example, 91% of parents reported that their 4th grader was achieving at or above grade level in reading, whereas the National Assessment of Educational Progress found that only 36% of 4th graders nationwide were performing at that level.

The Learning Heroes study attempted to understand the reason for this disconnect and how it could be remedied. “By having a more informed and holistic picture,” they said, “parents can find the best resources for their children at home and partner more effectively with teachers to keep their children on track for college and life success. They also can demand more of their schools.”

From interviews with parents, the study concluded that parents interpret good grades on report cards to mean that their child is performing at grade level academically. But two-thirds of the teachers interviewed said that grades on report cards reflect not only academic achievement but also effort, progress, and participation in class. In fact, nearly half of the teachers said that report card grades reflect effort more than academic achievement! Clearly, report cards as they are currently used in many schools are not a reliable indicator of mastery.

An interesting step in the study was seeing how parent perceptions changed if they were presented with information relevant to the disconnect. For example, some parents were told that their child received a “B” in math and didn’t meet expectations on the state test, and also that the child’s school received a performance rating of “C” in the state’s accountability system. With this additional information, the percentage of parents who said they thought their child was at or above grade level in math dropped from 88% to 52%.

It’s helpful to know that these types of information can improve the accuracy of parents’ perceptions. At the same time, schools need to address the critical underlying problem—that report cards are not conveying students’ academic performance accurately.

In competency-based systems, this problem is addressed in multiple ways. First, schools provide clear statements of the competencies on which students must demonstrate mastery, as well as learning objectives and associated rubrics that help students identify their performance levels and what they need to do to improve. Second, indicators of a student’s progress are made available transparently to students and parents. Third, performance on academic competencies is reported separately from performance on other competencies—including “personal success skills” or “habits of work and learning,” such as the effort and participation grades that teachers in the Learning Heroes study said were routinely averaged with academic grades.

Two excellent resources on these topics are the CompetencyWorks issue brief The Art and Science of Designing Competencies by Chris Sturgis and the Great Schools Partnership’s Proficiency-Based Learning Simplified website, which has extensive sections on assessment, grading, reporting, and related topics.

Assessing “Personal Success Skills” Separately

Assessing these skills separately is one of the key differences in competency-based assessment systems. It is essential for making sure that a “B” in mathematics isn’t really a “D” in content knowledge combined with an “A” for good behavior. It also helps students, teachers, and parents know where students stand in their learning progress in these distinct sets of competencies, which in turn helps them focus their effort on moving toward mastery in the areas where it’s most needed.

The “personal success skills” go by many names—essential skills and dispositions, habits of scholarship, noncognitive skills, 21st century skills, work study practices, and others—depending on the school or organization discussing them. There’s also no universal set of skills that schools focus on. At the Expeditionary Learning (now EL Education) school where I taught, each trimester’s report card provided separate “HOWL” (habits of work and learning) grades on preparation, organization, and participation. The National Center for Innovation in Education focuses on the “essential skills and dispositions” of collaboration, communication, creativity, and self-direction.

In addition to reporting personal success skills separately, schools need to grapple with ways of describing them and systematic ways to collect high-quality evidence about student progress on them. The NCIE publication just cited has done deep, thoughtful work on this. For example, for the skill of collaboration they identify five dimensions (self-awareness, communicating, negotiating & decision-making, contributing & supporting, and monitoring & adapting) and what those skills might look like when students are at the four levels of beginner, advanced beginner, strategic learner, and emerging expert.

Other Needed Supports

These aspects of competency-based education should help students and parents have a more accurate understanding of student progress toward competencies. However, the Learning Heroes report provides additional insights into what’s needed. One in three teachers reported that they feel pressured by their school or district administration not to give too many low grades on report cards. Many teachers said that they are reluctant to communicate negative information to parents, because they worry that the parent will blame the teacher or elevate the issue to the principal and cause problems for the teacher. A quarter of the teachers did not feel adequately supported by school administrators in conveying information about low grades to parents, and about half of the teachers had no formal training in having difficult conversations with parents. So while creating more transparent report cards that separate academics and personal success skills is essential, other issues also clearly need to be addressed.

Although I believe that these competency-based changes lead to parents perceiving their child’s progress more accurately, both the practitioner and the researcher in me do not want to assume this is true. Practitioners should still check in to ensure that parents understand how their child is doing, and researchers could devise studies to test whether competency-based grading actually does lead to more accurate parent perceptions. The Learning Heroes report is a great example of how research can provide persuasive evidence of the need for specific educational reforms.

See also:

- The Art and Science of Designing Competencies

- Proficiency-Based Learning Simplified

- EL Education Core Practices (especially Practice #24 – Communicating Student Achievement)

- Competency-Based Education Quality Principle #12: Maximize Transparency

- Essential Skills and Dispositions: Developmental Frameworks for Collaboration, Communication, Creativity, and Self-Direction

Eliot Levine is the Aurora Institute’s Research Director and leads CompetencyWorks.