New Haven Academy: Pedagogy Comes First

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is part of a series on mastery-based learning in Connecticut. See posts on New Haven Public Schools,Windsor Locks Public Schools, Naugatuck Public Schools, Superintendents Leading the Way in Connecticut, and New Haven Academy. Connecticut uses the term mastery-based learning, so that will be used instead of competency education within the series.

This is part of a series on mastery-based learning in Connecticut. See posts on New Haven Public Schools,Windsor Locks Public Schools, Naugatuck Public Schools, Superintendents Leading the Way in Connecticut, and New Haven Academy. Connecticut uses the term mastery-based learning, so that will be used instead of competency education within the series.

There is no mistaking New Haven Academy’s pedagogy and vision – it hangs from colorful banners above the school: Think Critically. Be Responsible. Get Involved. There is also loving attention to the social-emotional needs of students exemplified by the bulletin board in the main office:

Just remember it’s tough to enjoy life when you don’t like yourself. When you learn to succeed at being yourself, you’ll be well on your way to enjoying life more fully.

Don’t let the way another person treats you determine your worth.

Find something you like to do that you do well, and do it over and over.

Co-founders Greg Baldwin (principal) and Meredith Gavrin (program director) have an interesting story about how they came to the world of mastery-based learning. It’s a story shaped by how they operationalized the pedagogy at the center of the school and eventually came to the point where they had to make a full conversion to mastery-based learning, as grading and traditional practices of how students advance were just too out of sync with the rest of the school to ignore.

The good news – among the juniors who were the first class to use mastery-based grading, there is an increasing number of them achieving mastery in their courses.

From Habits of Mind to Mastery-Based Grading

Baldwin explained, “Before the shift to mastery-based grading in 2013, we were a project-based school using portfolios and exhibitions. Having a strong foundation in project-based learning was important before shifting to mastery-based learning, as our teachers know how to organize learning for groups as well as support individual needs of students. We value the learning that takes place in groups and in projects.”

“When we launched the school in 2003, the Habits of Mind from Deborah Meier informed our instruction,” Baldwin recounted. “We have gone through an evolution in how the habits inform courses, teaching, and assessments – we now think of the Habits of Mind as cross-curricular standards that are becoming the language of mastery.”

“When we launched the school in 2003, the Habits of Mind from Deborah Meier informed our instruction,” Baldwin recounted. “We have gone through an evolution in how the habits inform courses, teaching, and assessments – we now think of the Habits of Mind as cross-curricular standards that are becoming the language of mastery.”

NHA’s thinking about exhibitions has also developed. Baldwin continued, “We used to have big projects in the middle of the year that became exhibitions in every course. Our experience in developing rubrics developed at that time, as well. Then we began to have tenth graders create a portfolio of their work for an end-of-year exhibition. There was so much value in that process that we have expanded to have an exhibition for every grade.”

In 2009-2010, NHA started to contemplate how to have more authentic education and did more backward planning about how to integrate it, including redesigning rubrics. However, they were butting up against traditional grading because it wasn’t consistent with their values, pedagogy, or how they wanted to engage and motivate students. “There was a huge disconnect between four quarters, 0-100 points, and an F,” Baldwin said. “You could predict on September 15th what grades students would receive. It was time to take on the battle. The question was, how do we make grading more meaningful and a tool for learning and growth?”

In 2012, they put together a team of teachers, all of whom had been with the school for over six years, to begin to think through some proposals. They looked at several models and then created a grading policy that “put us in the right direction and then we jumped in.” When NHA made the shift to be mastery-based, two other important components were added: practice assessments (formative assessments) and core assessments. Completing a course and earning a passing grade is based on the core assessments. They separated academics from behaviors, removed Ds and Fs as an option, and organized core assessments around standards. Departments began to dive deep into instruction and assessment in the academic domains. NHA continues to make changes in the grading policy because, as Baldwin observed, “Students are always going to find ways to game the system.”

Before we jump into a deeper conversation about NHA’s insights into mastery-based grading policy, here are short summaries of their pedagogy and assessment structure.

Core Beliefs and Overall Pedagogy

New Haven values critical thinking – their goal is to “teach students to analyze information and ideas in depth, to consider multiple perspectives, and to become informed decision-makers.” Their pedagogical philosophy is that students need to be involved with inquiry-based learning, engaged in solving problems, able to reflect on their learning, and able to demonstrate their learning through performance assessments.

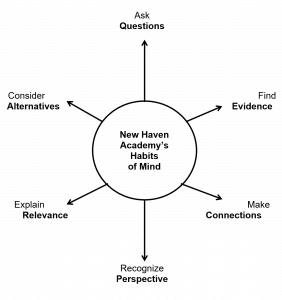

NHA helps build critical thinking skills through six Habits of Mind:

- Ask questions

- Find evidence

- Make connections

- Recognize perspectives

- Consider alternatives

- Explain relevance

This set of habits is related to the intellectual aspects of learning. They also have three areas of Responsibility – completing homework, participating in class activities, and meeting assessment deadlines – that capture the habits of work that students need to be successful.

Assessments

Assessment at NHA prepares students for the kinds of work and thinking required in college and the workplace. Students must successfully earn a number of credits in each discipline by creating a portfolio of Core Assessments that demonstrate their ability to do the essential work of that discipline. Students are regularly assessed as a way to inform instruction and to measure progress toward mastery through practice work and practice assessments, neither of which are part of student’s academic grades.

Exhibitions are an important part of NHA’s approach, with two types of exhibitions. One is discipline-based; the other is yearly focused on developing critical thinking and personal plans. Each has a different focus. For example, at the end of eleventh grade, students do an exhibition based on the three-week internship and college exploration that was completed as part of the early college program.

Grading

NHA’s core beliefs that were used in shaping the grading policy include:

- Students must master critical thinking, academic skills, and essential knowledge in each academic discipline.

- Students need time to practice and learn from mistakes.

- Students should have multiple opportunities to show what they know and can do.

- Strong work habits and community involvement are critical for success in college, career, and citizenship.

- Learning cannot be averaged.

The grading system at NHA is what I refer to as a hybrid – it’s kept some of the rituals of traditional grading, in this case an A, B and C structure, while making important changes to focus more clearly on learning. NHA has two kinds of grades: academic and responsibility (completing homework, participating in class activities, and meeting assessment deadlines). Baldwin noted, “Simply eliminating the D has raised the bar on how much work students need to do and the importance of the timetable to get work done.” Gavrin expanded on this with, “There are a lot of precursors to making the change in grading. You have to make the other changes first so that the grades have meaning. We wanted any change to be necessary and meaningful so some pieces of the system have been left intact until we have a much better idea of a better alternative.”

Baldwin began the reflection on the changes mastery-based grading has brought to NHA. “The mastery-based grading is engaging teaches because it is a better diagnostic tool,” he said. “When the grade is a clutter of academic, projects, and behaviors, there’s just no way to know what a C or a B stands for. Teachers are much more acutely aware of what is happening with students. A student’s behavior is good but they are really struggling. Or a student is keeping up with reading but having more problems with writing.” However, not every teacher has fully embraced the practices of mastery-based learning yet. Baldwin explained, “We warned our teachers that once they began to do mastery-based learning, they were going to feel like a new teacher all over again. That’s how big the change is. Whether teachers can easily make the shift depends on how comfortable they are in handing over responsibility to students.” (See NHA’s rubric for responsibility.)

Baldwin also noted that, “One of the biggest benefits of mastery-based learning is the clarity for teachers. We have had so many good conversations with teachers about what they are teaching, what they want students to be able to know and be able to do, and why they are teaching it. We know we are doing a good job at implementation, as it is making alignment a natural process.” The next stage of capacity building is likely to be on unit development and lesson planning. Among teachers, there is more conversation about why they are using a particular resources rather than just selecting “cool videos” and what specific skills they want students to be developing in any activity. Baldwin noted, “The selection of activities are more likely to be based on the skills students need and what students need to practice. There is more focus on what students need to do to learn something rather than simply covering the content.”

Referring to the Great Schools Partnership Proficiency-Based Learning Simplified model, Baldwin described an unanticipated impact of the new grading policy. They began to focus very heavily on learning and assessment with less attention to instruction. They felt that they were losing some of that innovative teaching they had developed over the years, partially because the clear focus on standards had introduced the concept of covering the standards. Baldwin suggested that the next focus is on helping teachers tap into the creativity that is enabled by the mastery-based structure to help them break out of the coverage mentality. This will require becoming skilled in developing units and creating more flexibility in the school schedule.

Gavrin noted, “The biggest sticking point we have encountered is that some teachers have observed that students have less sense of urgency or responsibility. There have been cases of students wanting to see what is on test first and then retake it. The mastery-based grading also helps you recognize very quickly the maturity level of students and when they need to have more structure and support.”

NHA has made the Responsibility grades matter: Students who are more responsible earn more time and support to demonstrate mastery on core assessments. Vice versa, if a student hasn’t been responsible in the basics of getting work done and participating, they may not take advantage of the flexible time. NHA is of course a very student-centered school, and if the low grades in Responsibility indicate a problem somewhere else in student’s lives, that is taken into consideration.

Gavrin also raised an interesting insight about a tension in mastery-based learning. “Any time you set up a system that says a project must be done, then you’ve set up a situation in which the project is more important than the deadline,” she said. “We want students to participate in all of the learning, so we don’t give a zero when work isn’t turned in anymore. However, that does open the door to students not putting in the effort they need to meet deadlines. This increases the pressure teachers feel to cover all the standards.”

Talking about new grading systems is hard because it is complicated. And if you get it wrong, you’ll have to spend a lot more time in conversations than you anticipated. I thought New Haven Academy’s explanation of the change in grading was worth sharing.

Meeting the Needs of Students

One of the big challenges we are facing as a field is that once we ask, “What skills have students mastered, not just in a course but within the full set of skills they need to be successful?” then we become responsible for ensuring they have the pre-requisite skills. The traditional system, with its time-based advancement policies, allows us to ignore this issue. This level of transparency is one of the reasons that mastery-based learning actually embeds accountability within the school system itself. However, it still leaves us with an instructional dilemma that we don’t have much research to draw from to guide us.

I really appreciated the depth of the conversation with Baldwin and Gavrin regarding how to meet the needs of students who are performing several grade levels below their grade level. Gavrin pointed out, “The challenge of meeting the needs of students with gaps in their skills existed before mastery-based grading. However, mastery-based grading makes you have to deal with it very directly. “ She explained that NHA does not track students and values heterogeneous grouping of students.

We discussed the risks of the different strategies. If students aren’t offered text that is on-level, or that is too easy or too hard, they might disengage. If they aren’t offered grade level text, they may not be getting the depth of detail needed to engage fully in analyzing or solving problems. NHA has found that heterogeneous classes with reading support workshops have been proving successful. However, some disciplines may offer students a better opportunity if they are taught at their own level. For example, they are using diagnostic testing for students who are working at their levels in math and Spanish. “Ideally, there are multiple points to engage students and use different instructional strategies,” Gavrin explained. “If we want every student to be successful, then we need to be flexible in how we are grouping students so they get what they really need. The solutions are personalized because it will differ for students, by discipline, and whether there’s an opportunity to provide additional support.”

“It is equally important to provide students with the opportunity to excel, to go beyond the minimum expectation,” Gavrin added. “We look for the natural points of expansion that students can pursue. We want our units to be designed like an accordion that can expand naturally without being entirely linear.”

Mastery-Based Learning as a Districtwide Strategy

I wondered how NHA was thinking about the district effort to introduce and/or enable mastery-based learning within the district. Baldwin reflected, “Schools are definitely interested in becoming mastery-based, but no one wants it to turn into a mandate. We know things work better when teachers have input. It may not be every teacher in every building, but we know that we need enough of a process to engage teachers effectively. There is also a tension when schools forge ahead and create structures and then have the district introduce a different one. Do we embrace the district version or do a translation?”

See also: