Ownership, Not Buy-In: An Interview with Bob Crumley, Superintendent Chugach School District

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the fourth post in the Chugach School District series. Read the first, second, and third posts here.

In October, I had the chance to meet with Bob Crumley, Superintendent of the Chugach School District. He’s worked his way up, starting as a teacher in the village of Whittier, becoming the assistant superintendent in 1999 and superintendent in 2005. Crumley has a powerful story to share, as he’s been part of the team that transformed Chugach into a performance-based system and sustained it for twenty years.

Crumley has tremendous insights into every aspect of creating and managing a personalized, performance-based system. The emphasis on empowerment, situational leadership-management styles, and courage reminded me of my conversation with Virgel Hammonds, Superintendent of RSU2 in Maine. Below, Crumley addresses several key elements of managing a performance-based system:

Personalized is Community-Based: On the Importance of Community Engagement

Creating a personalized, performance-based system starts with engaging the community in an authentic way. Our entire transformation started with the communities and school board challenging us – they wanted to know why their children were not reading at grade level. Our communities were not sure they trusted the schools and teachers. This was partially based on the history of Alaska and how Native Alaskan communities were treated. However, it was also based on the fact that we were not currently effective in helping our children to learn the basics or preparing them for success in their lives. We had to find a way to overcome that.

The superintendent at the time, Roger Sampson, was committed to responding to the community and implemented a top-down reading program. Reading skills did improve, but it also raised questions for all of us about what we needed to do to respond to students to help them learn. With the leadership of Sampson and Richard DeLorenzo, Assistant Superintendent, we took a step back in order to redesign our system.

Twenty years later, we are thankful for how our community guided us in the right direction through difficult-to-answer common sense questions, which we honored by building right into the new system. Should we expect all students to learn the same material, in the same way, at the same pace? Should we allow our system to hold back students who are ready to advance to new learning material? Should we advance students to new learning levels before they are ready? Should we consider the state-tested content areas as the most important, or consider all content areas equally important?

The common sense questions led us to responses, which reversed the traditional education equation. In our past traditional system, time – 180 school days per year – was the constant, and the amount learned by each student each year was the variable.

Community members from Tatitlek, Whittier, and Chenega Bay were involved in the process. Their description of what they wanted for their children helped us to understand we needed to approach students holistically. We needed to be able to prepare students for being successful in their lives – whether that was to live in remote areas, live in urban areas, go to college, work in a business, or create their own methods of supporting themselves. In order to be comprehensive, we created ten content areas that include academic skills, personal and social skills, and employability skills. Our community members also wanted to make sure that their children knew how to learn, so we began to think about the focus of teaching as helping students build content skills through, and with, process skills.

I think the biggest mistake that districts moving towards performance-based systems make is that they skip the community engagement piece. To community members, it quickly becomes “your system” and not “our system.” Too many districts glance through that step, and it always comes back and bites them. When we transform our schools to a personalized system, we have to start with being community-based. We simply can’t think about our students as outside of our own community.

Student Learning: The Core of System-Building

Early on, Sampson and DeLorenzo embraced a continuous improvement model that would be the foundation of the Chugach system. This resulted in CSD receiving the Baldrige award in 2001 and the Alaska Performance Excellence Award in 2009. We continue to be very focused on the continuous improvement approach in our strategic planning process.

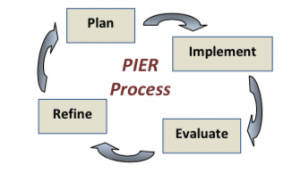

Continuous improvement processes are used by all high-functioning organizations to remain current with research, technologies, and to use stakeholder input to drive improvements. It’s necessary for both efficiency and effectiveness of any organizational system to remain at expected high levels of performance. An example of one of CSD’s continuous improvement process is the PIER process: the continuous cycle of Plan – Implement – Evaluate – Refine.

Continuous improvement processes are used by all high-functioning organizations to remain current with research, technologies, and to use stakeholder input to drive improvements. It’s necessary for both efficiency and effectiveness of any organizational system to remain at expected high levels of performance. An example of one of CSD’s continuous improvement process is the PIER process: the continuous cycle of Plan – Implement – Evaluate – Refine.

The entire system is designed around what we need to do to help students learn.

System-building is based upon stakeholders developing a shared purpose, upon which five major elements are developed:

1. Student Focus

b. Balanced Instructional Model

c. Authentic Assessment

d. Meaningful Reporting including an information system that supports all the users

2. Staff Focus

b. Developing Leadership

c. Developing Collaborative Communities of Learning

3. Leadership Focus

b. Institutionalizing innovation

c. Shared Leadership – a management strategy that is consistent with empowerment and motivational theory

4. Community and Communication Focus

b. A “Working Version” strategic plan

c. Partnering and collaborating to expand the menu of opportunities

5. Finance & Facility Focus

b. Routine, deliberate assertive alternative revenue seeking

c. Frugal, conservative budgeting and spending processes

The common theme across these five elements is centered on involving the students. If it doesn’t work for them, then it isn’t effective. They need to own the system. If they only buy into the system, then they can easily start resisting it. It is important that students, parents, and educators are in partnership towards a shared goal. Overcoming challenges as a team, shared hardship, can galvanize a team’s ownership.

In terms of system-building, the core focus needs to be on understanding student performance and student growth. We need to know three things about students: where are they in each of the content areas, how are they growing, and what is needed to help them get to the next step.

The entire system needs to be built around these three questions.

Empowerment: On Managing the Workforce

Empowerment is something I believe in strongly. I believed in it as a teacher to the point where I wanted them running the classroom. Students can take a great deal of ownership when the system is designed to do so. When we started down the road to transformation, we had to deconstruct the systems that were in place. We redesigned with the goal of student ownership, involving them along the way. If students are going to be empowered, so must the workforce be empowered.

The only way to manage an empowered workforce with empowered students is through a middle-up-down management approach that constantly seeks input and opportunities to distribute leadership. Superintendents who separate leadership and management do so at their own peril.

I’ve continued to cultivate a management style that would be effective in the personalized, performance-based system. One of the things that was very influential to my thinking was a meta-study from the American Psychological Association on what makes people happy. I took the three main ideas and translated it to what makes people motivated in the workplace:

- Challenge: People are happy when they are working on something fairly complex with some success. They’ll want to continue working with you if they are challenged.

- Social Context: People are happy when they can work with others in the context of challenges. There is great value when people have shared experiences that bring them meaning.

- Autonomy: People want to have independence about how that works gets done. In the workplace that needs to be done within a scope of work. My job is to determine what are reasonable guidelines to frame their autonomy.

These three ingredients are the foundational building blocks I used with students in my classroom, and I also use them now with my staff. It is absolutely critical that this approach is used consistently. You need to make sure your teachers are empowered if you expect them to support empowered students. I always return to these three elements when we are starting a new initiative or addressing issues raised through continuous improvement.

Delegation: Investing in Teacher Ownership, Not Buy-In

As a superintendent, my goal is ownership, not buy-in. When you have buy-in without ownership, you are left in a vulnerable spot whenever there is a bump in the road. When there is only buy-in, your stakeholders are going to point their fingers at you, “What are you going to do about it?” When you have a bump in the road when stakeholders have ownership they ask, “What are we going to do to fix it?”

I turn to the Hersey-Blanchard Situational Leadership approach to help me think through carefully what type of leadership approach to use. I depend on ‘participating’ and ‘delegating’ in most of my work. There have been situations when staff have needed more direction, but these tend to be the exception.

I don’t know the last time I made a district-wide mandate. They just don’t work, so I don’t manage through memorandum. For example, throughout our continuous improvement process, the issue of strengthening our approach to habits of mind came up. One of our student content areas is called Personal/Social/Service, which focus on the skills and attributes students need to learn to navigate their world. The habits we were using weren’t as aligned as we would have liked, and an advisor recommended a specific program that we could integrate into our model. However, I refused to pick one model and mandate it. Instead, we provided staff development opportunities for teachers to learn about the Habits Of Mind, the different approaches, and opportunities to practice using each approach. When it was time to develop daily lessons and assessments, it was clear that the Habits of Mind program was considered effective by our teachers because they all began used this framework with students on a routine basis. There is already talk about using the Habits of Mind framework to bolster our student standards during our next iteration of continuous improvement.

An important lesson I have learned over the years is that one of the important steps in setting guidelines for staff to work autonomously is to clarify that we are all acting in the interest of the common good. It’s too easy for staff to develop ownership as an individual path rather as a collective process, where it needs to be. Even though our communities are geographically separated from each other, we need to find policies and practices that work for everyone across the geographical isolation. We’ve built that concept into our teacher evaluation process so that teachers are recognized for making decisions that benefit their school and their district.

Balance: On Managing a Performance-Based System

The minute we changed the equation of time and learning so that time became the variable and learning the constant, we immediately faced the question: “How do we manage when we are individualizing the educational experience for kids?” All the systems in the traditional system didn’t help us anymore. We had to start from scratch.

We’ve learned that in order to manage in a performance-based system, we need to start with a balanced scorecard. When doctors do a check-up, they look at your heart, lungs, and weight. They consider it in terms of your height, gender, age, and your previous health status. We know that to have an accurate portrayal of our health, we need a balanced scorecard of indicators. The same goes for education. We need to have a balanced scorecard of indicators for our students, staff, and stakeholders to use to make decisions.

It’s important to send a message that the state testing indicators aren’t the end all, even if that’s the focus of state legislators. It sends a powerful message when the state only tests reading, writing, and math but not social studies or employability skills. As a district, we had to put into place a system that created a meaningful and balanced way to talk about student progress and our effectiveness in all areas. We believe all content areas are equally important. We dedicate staff development and resources on all ten content areas. We monitor progress and celebrate growth in all ten areas.

We started with folders and binders to monitor progress, but knew immediately we needed something more dynamic. At the time, there wasn’t any information system that could support us, so we created our own information system to support personalization (it’s called AIMS: Aligned Information Management System). We designed it so that everyone has access to information about where students are and how they are progressing, as well as management reports for educators, administrators, and district staff. We are working on a template for a dashboard that will take us to the next level of monitoring progress and early identification of problems.

We use data about student results in AIMS to help us understand how we are doing as a district. When there are problems, we take a look at the processes that are in place. Our staff work together to analyze the problem and develop strategies. We know that the way to improve results is dependent on staff and the effectiveness of our processes, so we make sure they are part of the solution.

Overcoming Fear: On Power and What to Do With It

My training as a teacher was as a sage on the stage. I was also a coach. I learned very quickly that my teaching style wasn’t as effective as my coaching style in building relationships and motivating students. I was much more effective in helping students learn and in helping teachers learn if I could empower them and facilitate the process.

The scary part of this style of teaching and managing is that to empower someone you must give away your own power. Once we had a shared purpose of what we wanted to accomplish, I gave the power to the kids. Everything went smoother, and discipline problems went away.

Of course, as an administrator, it’s even scarier for to give up power to teachers. When I first started to develop this management style, I was afraid I might lose all my credibility and authority. Then I realized I was just changing the source of my credibility and authority. And once again, everything went smoother.

State Mandates: Continued Opportunities for Improvement

I’ve learned to see mandates from the state as opportunities. We will meet the letter of the law, but we aren’t going to let the tail wag the dog.

For example, we have a state mandate about including state assessment scores in teacher evaluations. We have a great teacher evaluation tool developed by teachers and our administrative team. I’m not going to make any changes to the evaluation tool that causes a loss of ownership. Instead, I’m going to tell our teachers that there are state requirements we need to meet, and we’ll take this opportunity to see if we can improve the evaluation tool to help us get better at serving our kids.

If we said that we were doing it only because the state required us to, it would send the wrong message to teachers and students. We look to see the value and opportunities that develop when outside forces require us to change and adapt. Continuous improvement is a core value and process at Chugach School District.