Red Bank Elementary School: Teaching Students, Not Standards

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post is part of the series Competency Education Takes Root in South Carolina. This is the second in the series on Red Bank Elementary in Lexington School District. Begin with the first on five big takeaways and follow along with: #2 teaching students instead of standards, #3 teacher perspectives, #4 student perspectives, and #5 parent perspectives.

This post is part of the series Competency Education Takes Root in South Carolina. This is the second in the series on Red Bank Elementary in Lexington School District. Begin with the first on five big takeaways and follow along with: #2 teaching students instead of standards, #3 teacher perspectives, #4 student perspectives, and #5 parent perspectives.

Red Bank Elementary offers a great example of how districts can take a big step toward high quality competency education by allowing schools to move ahead when ready. It’s also an example that schools can go far down the path when districts don’t hold them back from innovating.

It says a lot about the leadership at Lexington School District that they have been supportive of Principal Marie Watson and the team at Red Bank as they took the enormous step five years ago to work with the Reinventing Schools Coalition to transform their school into a personalized, competency-based school. Susan Patrick and I had just completed the scan of competency education five years ago and hadn’t even started imagining CompetencyWorks at that time. It’s this kind of district leadership, to support innovation wherever it develops, that is needed to transform medium and large districts.

Red Bank Elementary is in the Lexington, South Carolina district a bit outside of Columbia. The school serves a socioeconomic mix of 580 students with about 56 percent FRL. The school has a bilingual Spanish Immersion program serving 30 percent of the students. Many of the families were hard hit by the flooding in the fall of 2015. Another thing you should know – South Carolina has its own set of standards, called the College and Career Ready standards, that have been described to me by one educator in my travels in the state as a “tweaked version of the Common Core.”

What’s Happening in Red Bank Classrooms

Red Bank is entirely organized around learning and leadership (leadership is a district initiative). It starts before you even walk in the door of the school with a sign for students coming in late: “Parents please check in at the office, learning has begun.”

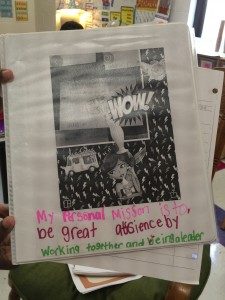

The dominant feeling is of a quiet joy mixed with a good dose of respect, hope, and aspirations. There are lots of hugs, constant reminders of the qualities of leadership that everyone is aspiring to, and clear, clear, clear focus on learning. Staff are unified by a commitment to do better for kids and to intentionally improve their school based on a clear set of values and understanding of learning and teaching. After spending a few hours at Red Bank, I just wanted to do my personal best (it may have been the sign that says Everything you need is already inside you that gave me that lift).

Red Bank has taken many of the rituals of personalized learning that I’ve seen in other schools, mixed it with the The Leader in Me program, and then lifted it up into almost every aspect of the school. For example, two students, Hunter and Reilly, gave me a tour of the school, guiding me through hallways named Kindness Avenue, Creativity Lane, Perseverance Path, and Compassionate Way. Hunter and Reilly talked to me about what they like to study, when they like to do their work on a computer and when they like to work in a group, and how they get to make things, “really make things, like windmills” in STEM class.

In almost every classroom, I saw evidence of the protocols needed in a personalized classroom to enable student agency. There were shared visions created by students in the classrooms. The codes of cooperation were being actively used to engage students in reflection about how they were doing in demonstrating the behaviors needed to support learning. Standard operating procedures were dotted throughout the school on a number of issues – getting started for the day, learning how to revise your writing, and knowing what to do if you get stuck.

In most classrooms we visited, the teacher was at a table working closely with three to five students. The other students were all distributed around the room working independently or in small groups. Every classroom had students working in stations, with teachers pulling the class together as needed. As always, just about every student was on task. In some classrooms, teachers were using music to help students make the transition to the next activity. I had to beg one student who was advancing beyond the other students to take the time to show me the project where he had created a model of his community. He noted that the size wasn’t entirely proportional as he wasn’t able to measure the height of the buildings.

In one class I noticed that students were working within three topics and being grouped and regrouped around five different standards. Watson explained that the district has organized standards into “topics,” but the teachers felt they needed to group and regroup students around standards. One teacher mentioned that the ELA standards are sometimes too broad and need to be broken into even smaller stepping stones. Assuming the Lexington School District takes further steps toward competency education, it will be interesting to see how their thinking develops around topics.

In one class I noticed that students were working within three topics and being grouped and regrouped around five different standards. Watson explained that the district has organized standards into “topics,” but the teachers felt they needed to group and regroup students around standards. One teacher mentioned that the ELA standards are sometimes too broad and need to be broken into even smaller stepping stones. Assuming the Lexington School District takes further steps toward competency education, it will be interesting to see how their thinking develops around topics.

In one classroom, Takyjah greeted me as that day’s ambassador. She showed me how she tracks her learning, her notebooks filled with artifacts, and some of the projects she had done to demonstrate her learning. She was emphatic that she wanted to become better in social studies as she was already pretty good at ELA and math.

In one of the Spanish immersion classes, two teachers were working with fourth and fifth graders within two classrooms that had a smaller space between them. One teacher had engaged the entire class; in the partnering class, students were building up their vocabulary. Watson explained to me that although resources had led them to organize the classroom this way, the benefit was that it was creating more demand to be able to personalize learning and have students working at different levels. As always, teachers were on their own learning trajectories to prepare for and learn how to have greater personalization for students to be working on different units and academic levels.

In my conversations with students throughout the day, the only thing I felt wasn’t as consistently developed as I’ve seen in other schools using these personalized classroom protocols was that students were not always clear on the purpose of their activities or what step was going to be next. There was a bit more dependence on the teachers to be the “keeper of the meaning.” However, I also want to say that we walked into a lot of classrooms. We know that we are all in a process of transitioning, and teachers are on their own learning curves. So I may have just stumbled onto this issue in classrooms where teachers are building up their skills elsewhere.

Furthermore, Watson pointed out that as new teachers join the school, each one of them has to unlearn the fixed mindset of the traditional system and learn the new rituals and practices of a personalized, competency-based school. This is one of the “costs” that schools have to bear when they become competency-based before the district. When districts are able to upgrade their human resources to support competency education and create personalized, professional development strategies, the costs of training new staff can be distributed across the district.

Strategies for Blending Instruction

One of the highlights of my visit to Red Bank was the conversation with Watson; Jennifer Carnagey, literacy coach; Jamee Childs, technology specialist and instructional coach; and Dawn Harden, assistant principal.

Red Bank is developing what I would call an organic process to develop blended learning. Students have a lot of access to online learning through 1:1 iPads. There are elements of what Christensen Institute would call a flex model, but it doesn’t feel like online learning is the backbone – nor is it used the same in every classroom. Perhaps it is early in their process of their integrating online tools in the delivery of instruction, or it may be that another model is being created. (This will be discussed more in my posts about my visit to Charleston, SC as they too are integrating online learning in an organic fashion.)

Childs explained that the efforts to introduce blended learning came after competency education. “I would definitely recommend staging blended after competency education. You want the mindset in place to be able to choose tools that work best for you. You don’t really know what you need until you’ve organized your school around students and where they are in their learning.”

Carnagey pointed out, “Online learning isn’t necessary for competency-based education. When we started, I was a second grade teacher in the immersion program. We developed new practices such as unpacking standards, learning to organize several ways for students to practice before they were assessed, and data notebooks to track progress. The big change for me was to plan units so there several ways to practice, as some students are going to need more opportunities. It took a bit to get used to having options rather than a set assignment. I think of them as learning menus now.”

She expanded on what is needed to manage a personalized classroom with, “The shared vision and code of cooperation help create a sense of responsibility among students that this is their classroom. In addition, you must have procedures for students working independently. It won’t work otherwise.”

Carnagey emphasized, “People forget that blended learning is both face-to-face and online. They only focus on the online. However, there is a time and place for papers and pencils. It can’t be all or nothing. We put a survey out to kids and received very interesting response. They actually want to write with pencil and paper rather than type on the iPad.” Watson expanded on this point with, “The iPad is for work. It’s not an award nor should it be used as punishment. It’s a tool for learning just the same as pencil and paper.”

“We don’t want to lose sight of how important the teacher is in a blended environment,” Childs added. “When we select products, we want to make sure they are a really good fit. We want to make sure they address the standards. If a product isn’t promoting one of the four Cs – collaboration, creativity, critical thinking, or communication – then it is probably drill and kill.”

Given that vendors haven’t designed much around higher order skills, this means Red Bank only uses a few programs. They have a subscription for Reading A-Z and the digital platform Raz-Kids for independent, leveled reading in both English and Spanish. In math, teachers are use Compass Odyssey to provide opportunities for additional instruction, practice, and formative assessments based on their current level of progress towards mastery. As the math component is available in Spanish and English, teachers often use it in the Spanish immersion classrooms.

In my conversations with students, the topic of Compass Odyssey came up, particularly regarding the videos and quizzes students can access for instruction and assessing their progress. Everyone agreed that it was “no fun to get an 85 percent or less on a quiz because then you have to start all over.” Most agreed that it was important to do a refresher before you take a test. Students mentioned fluency several times and the value of the online apps to building it. The students described that becoming fluent was about being able to do something well enough that you could do it quickly. Students cited First in Math as helping them with fluency in math.

Scoring and Assessments

Childs highlighted that one of the challenges most competency-based schools confront at one point or another is grading. “What does the 4 mean in scoring student learning? If you are proficient, then what does it look like to go beyond? A 4 doesn’t equal 100 percent. It means you can take what you’ve learned and create something new. It really should be a demonstration of learning at the level of application.”

As Childs pointed out, however, “That raises another issue, since students will likely need to be involved with some type of project to demonstrate application. How do you make sure kids have opportunity to do project-based learning when you have so much to cover?”

Our conversation then moved into ways to either reduce the amount of “coverage” or create opportunities for more applied learning. Ideas that were mentioned included weaving ELA into social studies, creating the conditions for the ELA standards to be applied in the context of social studies, and rethinking the annual calendar and schedule.

Carnagey pointed out that to do this, “Teachers need to be able to know their standards really well. They need to know them so well they can organize them into the building blocks of a learning progression that help students move from one point to the next. They need to be able to do backward planning so that units are fully aligned and have choice for students as well as adequate materials for students who are going to need more time to practice.”

“From a coaching standpoint, we start by looking at the assessment or end product you want students to be able to do and then ask, ‘How are you going to get them there?’” Childs added. “Teachers are becoming more purposeful about pre-assessments in math, as they are so helpful in making sure students get refreshers for any prerequisite skills if needed. ELA isn’t as linear as math. It’s more of a continual process of building skills.” Harden added, “We used to have lots of activities. Now every activity is meaningful and challenging.”

—

I can’t wait to go back to Red Bank and Lexington School District in a few years to see how they are advancing. There are a lot of benefits when one school is competency-based, but there is an entirely richer set of benefits when there are competency-based pathways for students.

See also: