Thinking Ahead: AI in Math Education

CompetencyWorks Blog

As a senior in college, I can reflect on all the frustrations I experienced learning math in K-12. Often, the pace of my math classes was either too slow or too fast, and I wasn’t confident or comfortable with the material I was learning. I didn’t know what questions to ask during class, but I knew when I got home, I would be stuck on the homework for hours. I discovered Khan Academy later in high school–a flexible classroom environment that helped me with difficult concepts, but it wasn’t until my college years that generative AI became more mainstream as an advanced learning tool. I wondered: How might my relationship with math have been different if I had learned in a competency-based environment using AI? I also wondered what else would have been changed with AI, be it the role of teachers or the boundaries of the classroom.

AI is growing and evolving as a tool in K-12 instruction, and its use in classrooms will shape how students like me learn. AI can help with a lot of things– from building competencies to creating study guides. Educators and students alike should be aware of the abilities and implications of AI and begin to think critically about its use. In this blog, I take you along my journey reviewing existing research to discover where the known limitations of AI in K-12 education lie, focusing on math education. I explore AI’s potential capabilities and limitations in empowering personalization of instruction, increasing student engagement, and complex problem-solving in math education.

Applying AI to Learning Math

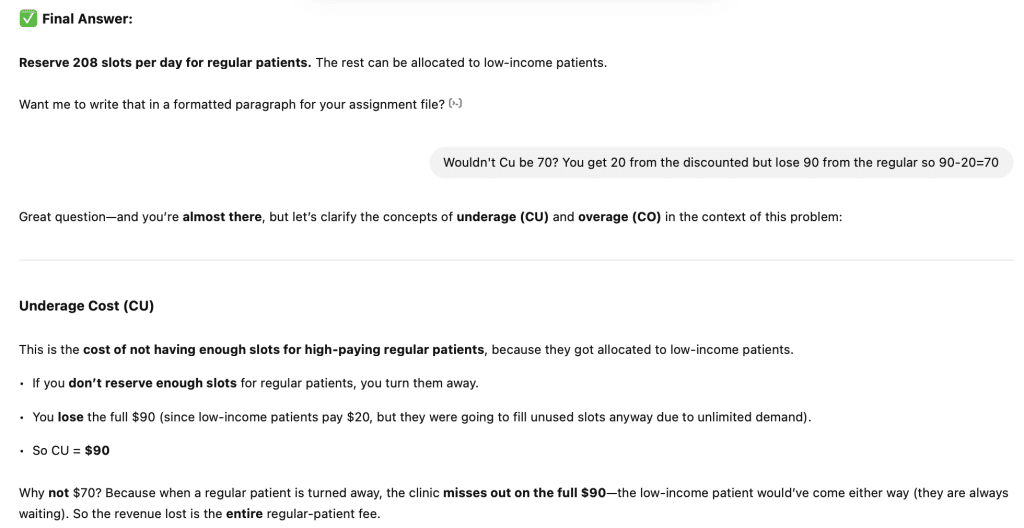

As a college student who leans on AI to brush up on Excel functions and statistical concepts, I am navigating how to use AI to help me learn. I am often challenged by my ability to effectively prompt Chat-GPT. I have to think differently when using generative AI in order to produce a reliable result. I use AI to check my logic on math concepts that I am struggling with. Below, you can see a screenshot from a concept in my Operations Management class that was confusing me. As a learner, I had to articulate what I wasn’t comprehending to challenge Chat-GPT’s answer with what I believed the answer to be. Chat-GPT was able to give me feedback based on my prompt and clarify exactly what I misunderstood. When I engage with Chat-GPT, I am actively engaging in the learning process and learning where the gaps in my understanding lie. When used correctly, learners can practice metacognition by using Chat-GPT to correct their misunderstandings and gain agency in their learning.

AI as a Teacher’s Assistant

In recent years, there has been a lot of experimentation to see if AI can become an assistant for educators, a supplementary tool for both the teacher and the student. Three prominent roles have emerged in research as opportunities for AI to support in the classroom:

- Intelligent tutoring systems: AI can be used to detect learning gaps and provide targeted support for students who may be ahead or behind the class. Where teachers may not have the bandwidth to address each student within the limited class time, AI tutoring systems can provide extra support.

- Assessment agents: AI can analyze student progress and generate reports. Instead of placing the burden of collecting and analyzing classroom data on teachers, AI can sift through various data points from homework and assessments and provide feedback for teachers. Performance assessment is a crucial use-case for AI, as it could streamline the amount of work teachers must do to personalize learning for all their students.

- Virtual teaching assistants: AI can support lesson plan and assessment design. ColleagueAI is one example, explored in this research article, of an AI platform that aims to make rubric-creation easier for teachers.

AI as a Facilitator of Student Agency

Generative AI Chatbots have several strengths that can help expand the possibilities of classroom instruction. Generative chatbots such as ChatGPT, Google Bard, and Wolfram Alpha have sophisticated language modeling that, when used effectively, can assist students in different aspects of solving math problems and applying their knowledge. If the student’s goal is to understand the process of solving a particular problem, the chatbot can provide a step-by-step explanation. If the student wants to identify where they are making a mistake and what concepts they lack understanding in, generative AI can help identify the specific concept and generate resources for the student to review. Having learned from the supplementary resources, if the student wants to test their knowledge, generative chatbots are useful for producing similar problems that assess competency on a topic. AI can also be used to model math concepts for students like me who struggle with visualizing concepts and 3-D shapes. The uses of AI are boundless, and when students know how to use the tools they get to be as flexible as they want in their learning because they are in control of what, how, and at which pace they learn.

AI not only has powerful analytical and assessment capabilities, it can also make learning more enjoyable. AI has enabled the gamification of math learning, stimulating problem-solving analysis through creativity. Examples of AI-powered math game platforms include Matific and Prodigy. Part of helping students enjoy math is boosting students’ confidence. Generative AI is good at providing hints and prompts in its feedback to help students solve problems on their own, which can build their confidence. Instead of being a crutch, AI can give students more agency by guiding them through the mechanics so they can feel ready to do it themselves.

Limitations of AI in Teaching and Learning

When incorporating AI usage into the classroom, it’s important to be clear on its limitations. These limitations include AI hallucinations that produce incorrect information and reduced accuracy in higher-order thinking abilities. One study explored both mathematics teachers’ successes and limitations in using AI for generative purposes. It’s important for teachers and students to be informed about the limitations and risks of using AI for learning. In fact, the Institute for Ethical AI in Education has published an ethical framework for teachers to reference when using AI in their work. Guardrails like these are important for the field to protect teachers and students from AI misuse.

When I started college, I was very skeptical about Chat-GPT and AI, and a novice. My first AI-driven project was in my Strategic Management of Business class, where we had to train Chat-GPT like it was an intern on our company’s team, so that it could provide recommendations for the company strategy. I actually didn’t do as well as I thought I would on this project, because I lacked understanding on how to use AI as a complement to my skills and higher-order thinking. Instead of driving AI with my thinking, I let AI drive my thinking. As a takeaway from this experience, the proper technique for using AI needs to be formally taught to students and teachers who want to incorporate AI in learning.

Evaluating AI: A New Challenge

So, if we believe the potential benefits outweigh the risks, how can we ensure the ways we use AI effectively support teaching and learning? How do we measure the performance of AI tools, and how can we calibrate and correct them? In the evaluation of human teachers, there have been various frameworks and measurement tools developed. Harvard’s Mathematical Quality of Instruction (MQI) framework is a rubric that helps assess a teacher’s quality of teaching mathematics. Many of the components of the rubric are transferable to evaluating AI, such as evaluating the precision in language and notation, or meaning-making in mathematical ideas. But should there be more indicators? Should AI be held at a higher standard?

I think, yes. Unlike a human teacher, AI does not have critical thinking skills. It cannot automatically apply corrections from one context to other contexts because it lacks nuance in its decision-making– at least for now. AI tools in education require a more granular level of scrutiny to ensure students are not misled with misunderstandings that go uncorrected.

AI also cannot make moral judgements the way human teachers can. Math is not just numbers; its application has real moral and ethical implications as well. AI, if it is not properly implemented, may hinder learning and development by encouraging plagiarism and unoriginal thought. To ensure AI remains unbiased and ethical, the field needs to develop more formalized rubrics to measure AI’s bias and moral soundness in the classroom.

The Bottom Line is Balance

Despite its limitations, AI remains a powerful tool to improve the instruction and learning of mathematics. AI’s ability to quickly build out lesson plans aligned to competencies, analyze and summarize learning data, and generate creative project ideas complements the work teachers do every day to implement competency-based education. This can free up time for teachers to provide students with more individualized support and one-on-one time. For students like me, who just need a little extra time and a fresh perspective on math problems, AI may enhance the learning experience and transform frustration into continued learning. Schools will have to find a balance between AI-driven personalization and human guidance, leveraging AI as a supportive tool to complement educators’ expertise and create a competency-based learning system. In fact, the School Teams AI Collaborative is exploring this very question – examining how practical applications of AI can build upon the brilliance of educators – not replace them – to drive meaningful instructional outcomes for learners.

Gugma Vidal a former Aurora Institute Intern. She is a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where she studied Public Policy and Business Administration. She is especially interested in health equity and is now attending Emory University for her Master of Public Health in the Fall.

Gugma Vidal a former Aurora Institute Intern. She is a graduate of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where she studied Public Policy and Business Administration. She is especially interested in health equity and is now attending Emory University for her Master of Public Health in the Fall.