Three Take-Aways

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post and all images originally appeared at Mastery Collaborative on February 27, 2018.

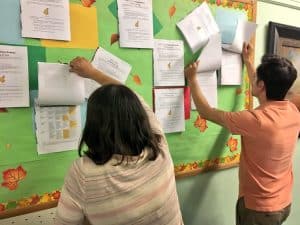

Recently Meredith Matson, Assistant Principal/Mastery rockstar, facilitated a professional development about enriching rubric criteria for the staff at MC Active Member School Urban Assembly School of Design and Construction. Below, three take-aways from Meredith’s session.

1. Rubrics too often contain “laundry-lists.”

Learning tasks should push students to higher-order thinking. Because rubrics guide these tasks, the criteria for mastery should reflect the deep thinking students need to engage in.

Non-example: Cite at least three sources.

Example: Provide sufficient evidence and reasoning to support your claim.

2. The value of transitioning from task-based to skill-based rubrics

In order to push the depth of knowledge/richness of criteria, focus on durable skills, rather than task-specific minutiae. Higher education programs generally don’t (yet!) prepare educators to teach in a mastery-based environment, it’s natural for teachers to gravitate towards the task-based rubrics used in traditional education.

To help her colleagues to move away from task-specific rubrics, Meredith asked them to first think about the skill or skills a given assignment is designed to assess. Then, to create criteria for mastery of that skill. (What would it look like to use evidence successfully to support an argument?) Focusing on higher-order skills, rather than on aspects of task completion, increases the rigor of rubrics—and makes expectations more transparent and contextualized for students.

3. Zeroing in on criteria for what genuine mastery looks like

A teacher commented, sagely, that teachers gravitate towards “laundry list” rubrics in an effort to make the learning criteria more demonstrable for students. While this is an honorable impulse, it rests on the false assumption that learning can be captured in laundry lists. For example, it’s easy to imagine a student citing three sources, and still not having evidence to support a claim adequately.

Without laundry lists of criteria, teachers need to get even more clear about what it looks like for students to demonstrate their mastery of skills and knowledge, for real. Assessment and grading is nuanced, but getting closer to the heart of what “mastery” looks like is where the power of this shift lies.

See also: