Waukesha STEM Academy: Personalizing Instruction and Learning Experiences (Part 2)

CompetencyWorks Blog

This article is part of a series on personalized, proficiency-based education in Wisconsin and the second in a four-part series on Waukesha STEM Academy. Read the entire series with posts one, two, three, and four.

This article is part of a series on personalized, proficiency-based education in Wisconsin and the second in a four-part series on Waukesha STEM Academy. Read the entire series with posts one, two, three, and four.

Many people describe WSA as a STEM school or as a project-based learning school. Murray quickly pointed out, “I couldn’t really make a blanket statement that we are a project-based school or not. It really depends on the student and how they learn best. For some students, hands-on learning and projects all day work great; for others, not so well. We organize the instruction and learning around what works for students.” He continued, “We started out as a project-based school until we discovered that not every student is ready to do hands-on learning the day they walk through our doors. We failed forward and learned by doing and not doing. Now we ask and discover through conversations with our students what the best fit is for them and roll from there. What does the student need? What type of environment do they like? What type of modality fits their learning habits best? What type of seat do they like, even! Maybe their best fit is direct instruction from a teacher, possibly a slide-show or presentation, maybe it is to watch a video so they have some control and can re-watch, or maybe what they need to do is create a video to teach other students.”

Instruction

The shared pedagogical philosophy at WSA begins with making learning visible. This starts with an agreed-upon workflow process that has students able to access ‘playlists’ or the resources they need for the unit or progression of skills, followed by students planning for and engaging in learning. The next stages are skill building and practice tasks and experiences with formative feedback, which is then followed by summative work where students submit artifacts that demonstrate their proficiency for a specific level of skill and demonstrating mastery. Finally, the learner continuum is used to monitor and share student progress to help support a competency-based learning system. And the cycle begins again.

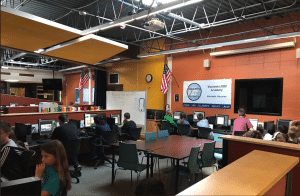

As emphasized above, the specific instructional strategies vary based on a combination of student needs and the teacher’s professional judgment about what will be most effective delivery and modality for students. There are different instructional modalities, including direct instruction, complementary and adaptive educational software, Socratic seminars, problem-based learning, and project-based learning. There is an emphasis on students applying their learning through the design process, innovating and creating things, capstones projects followed by gallery walks, and project-based learning. Murray explained, “It really feels unique and pretty real when you walk down the hallways and into learning spaces here, because you don’t see just STEM at WSA, you actually have to step over it.”

WSA knows that teachers need time for planning. Given the high degree of interdependence of math skills, with students needing to access prerequisite concepts and processes, the math team has 80 minutes [together] every day for planning and strategizing for providing support to all students. “When we sat back and reflected on our schedule for about the hundredth time in Year 3,” Murray laughs, “we recognized that we truly needed to be responsive to our teacher’s needs and not just our students’, or burnout was sure to follow. Similar to how a teacher would ask a student how they learn best, I asked our staff how they would work best, and they gave some amazing feedback and a vision. This vision blended with our students’ needs and brought upon our new daily and weekly framework, which is quite fluid to support needs of all learners in the school.” Feedback was then gathered from students, staff, and parents to continue to grow the best possible framework for optimal learning and teaching conditions.

Mix of Courses and Educational Experiences

Before WSA made the transition to personalized, proficiency-based education, there were eight core courses and transitions a day. “With that many transitions and classes came that much less time to learn and time wasted moving between classes,” Murray says. “What if we didn’t have bells, reduced the amount of transitions between classes, and built up the amount of time that students were able to spend on experiments, projects, and collaboration? What if we just gave students more time to apply their learning and opened up the pacing a little bit?” It seemed to be the switch that needed to be flipped, because engagement and performance skyrocketed, and WSA currently organizes their day into four main COREs, as they’re called. Murray insists that the day isn’t a block-schedule and there is evidence to prove it. “When we visited other schools or teams come to visit us, they quickly ask if our schedule is a block schedule when they see it and I show them the past two, three, and four weeks that we have just experienced. Every single week this year has been different for the most part, based on what took place each week – which trips were built in, which mentors and partnerships came to visit, when Advisory took place, and when we felt the need to build in a FLEXible afternoon, where students created their own schedule for half of the day. Folks aren’t sure how to take that, but it excites them when they see that it’s possible.” Murray shared that at WSA, they even run mornings and half days where the students are able to visit Passion-Project Seminars based on their own interests and, at times, the students are the ones who are running the seminars.

The day is typically composed of four main COREs, which include math, literacy, and science, as well as electives and STEM Pathways courses. Every other day, students have music and phy.ed., and on opposite days, they are able to select seminars from a course-catalog named STEM Pathways. “Traditionally, students don’t get any say in what courses they take in middle school, but we wanted to change the game and have students take some ownership in building their own Pathway based on what they love to do in their own lives – not what teachers love to teach about.” They are also seeking ways to ensure that students can access high school level courses, as they continue to roll out high level engineering, business, art, and cultures courses. For example, WSA is working with University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee to provide a high school biology course for students and has also partnered with Nobel-Prize winning science labs.

The courses at WSA consist of units designed for students to work at their own performance levels and different paces. Teachers organize the units, so whether a student is working at the sixth grade level or a ninth through twelfth grade level, they are clear about their target, the rubrics, and what proficiency looks like. Most of the classes use a workshop model or are organized around projects, where students may pursue theme-based activities and application of skills. In the workshop model, much of the skill building and practice is done within the classroom, while students pursue background knowledge and research in the evening hours.

WSA has created four STEM Pathways: STEM University (exploring how physics, electronics, engineering, chemistry, and nanotechnology can be used to solve problems); STEM BIZ (marketing, investment, graphic design, and administrative skills); STEM Cultures (world languages, world conflicts, social action), and STEM Art Studio (ceramics, jewelry design, 3D pen creations, fashion, and clothing design). (Please note: WSA is really STEAM by including the arts.) Every six weeks, students choose a seminar within their pathway and the options are different each rotation. Students can also always switch between pathways throughout the year, so that they truly find the niche area that is most agreeable and aligned to their interests and skill sets.

WSA values interdisciplinary learning. Murray explained, “We don’t want to isolate students in grade levels based on a born-on date, and we don’t want to isolate concepts. We want to create meaning in context.” Although the core courses are organized around the academic domains, it is likely that problems and projects are going to support students as they seek out opportunities for interdisciplinary thinking. WSA’s emphasis on creativity demands that students learn to think and use content/skills across the disciplines. Furthermore, the STEM Pathways options offer additional opportunity for interdisciplinary learning.

Capstone Projects play an important part in the student experience at WSA. Students complete three major capstones a year, which they pursue through a focal time named STEaM. When it comes to STEaM, there is a fine blend of each of the core courses, as there is a need to bring in all of the skills that the students have been working on, as well as progressing forward in other areas through experiential learning, to problem-solve and create solutions to large scale problems and projects. This process results in a portfolio of eighteen total capstones by the time students complete their five-hundred and forty day journey at WSA. Each rotation of capstone projects offers options for for the students and if they find no interest in any of the projects, or have done them before, they may build a student-proposal option. Since this is pretty heavy in the independent work area, students must track down two recommendations from teachers, which show that they have demonstrated habits of success and are competent to co-design a capstone project with the support of a mentor.

A Look at Mathematics

Mathematics has some specific features that has implications for proficiency-based schools. First, it has the longest span of skills, stretching all the way from kindergarten through twelfth grade. Second, there is both conceptual and process prerequisite knowledge required for each set of new skills as students move through their learner continuum. With approximately 60 percent of the students at grade-level in math, WSA’s math team had to reorganize their courses and units to be able to accommodate the other 40 percent, who were above or below grade level. They created four core courses of math so that students could be grouped, with the ability for students to move up based on readiness, not on time. Grade level textbooks were problematic as they didn’t relate to where students were or how to scaffold so that students actually built the lower grade level skills they would need for higher level skills. Thus, the math team also began to pull out what they needed for curriculum from different resources and online, adaptive platforms and programs. The playbook needed to be created so that when students were ready, so was the learning.

Educational Resources and Experiences

“We decided that we wanted to change the game and no longer wanted to fail with fidelity by hosting a set curriculum for a year. We didn’t want to take the Day 1, Page 1 and Day 50, Page 50 approach to a roadmap of lesson-plans,” Murray declared. He explained that once they began to rethink how the learning was organized and the use of time, they also came to the conclusion that adopting a single curriculum and then reflecting at the end of the year on how it worked [or didn’t] made no sense. He emphasized, “The model of adopting a curriculum for an entire year is broken and defunct. That is 180 days of a kid’s life. If it isn’t working, if they aren’t getting the support they need, then we need to step back, reflect, admit it and provide them with something else.”

They began to think about what they really wanted for students. Too many of the products were pre-packaged, with students all expected to do the exact same thing in the exact same way. Where is that ever realistic, for anyone? They wanted it connected to real life as much as possible. They wanted students to use the skills and content knowledge in ways that would allow them to understand how to apply them and to build the higher order skills. The math team, instructional coach, and Murray started searching OER and adaptive platforms, while challenging themselves to think deeper about how they could expose their students to real-world environments and challenges by applying learning in context and not just mastering content.

– – –

In the next part of this series, we’ll take a look at WSA’s use of resources (schedules, calendars, and space), their grading system (communicating student progress), and how they build the habits of student success.

Read the Entire Series:

- Part 1 – Buzzing Toward Personalized Learning in Wisconsin

- Part 2 – FLIGHT Academy: Magic Happens When Kids Come Together

- Part 3 – Blair Elementary School

- Part 4 – Creating a Learner-Driven System in Waukesha (Part 1)

- Part 5 – Waukesha STEM Academy: Personalizing Instruction and Learning Experiences (Part 2)

- Part 6 – Waukesha STEM Academy: Rethinking Space, Time, and Reporting (Part 3)

- Part 7 – Waukesha STEM Academy’s Journey from ABC to the Learner Continuum (Part 4)

- Part 8 – Kettle Moraine: Where the Future of Education is Being Created Student by Student

- Part 9 – Kettle Moraine: How They Got Here and Where They are Going

- Part 10 – The Five Pillars of Teaching and Learning at KM Explore

- Part 11 – The Sound of Learning at Create House at Kettle Moraine Middle School

- Part 12 – KM Global: Pedagogy, Curriculum, and Learning Design

- Part 13 – Chasing Competencies at KM Perform

- Part 14 – Reaching Out into the Community at High School of Health Sciences

- Part 15 – Practicing What They Preach: Micro-Credentialing at Kettle Moraine

- Part 16 – Distributed Leadership at Kettle Moraine