What I Am Learning from Anthony Kim

CompetencyWorks Blog

Sometimes I’m a little slow.

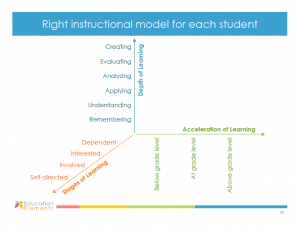

I loved the ideas that Anthony Kim, CEO of Education Elements, put together in his post Interested in Innovative School Models? What to Consider to Make Sure They Are Successful – merging together 1) depth of learning, 2) acceleration of learning, and stages of student independence or student agency.

But it wasn’t until I had the opportunity to hear Kim present at the New Hampshire Educators Summit last week (click here for video) that I actually started to really comprehend what this all means. And honestly, my guess is that these ideas are so profound that I’m just starting a journey of understanding what this means for competency-based schools. (I might call these types of inquiries a “learney” – a journey of learning.)

One of my huge pet peeves is that a lot of writing about blended learning only talks about the tech part and fails to provide an overall picture. Rarely does it talk about what is needed for blended learning to address the tremendous change that is happening with the introduction of the Common Core – moving from a focus on recall and comprehension, the first two levels in most knowledge taxonomies, toward the higher (and deeper) levels of analysis and application. Much of the knowledge base on blended learning focuses on models, products, and the necessary tech infrastructure….but not about what needs to be happening the rest of the time in the classroom to provide deeper learning.

Kim did not fall into this trap. Instead, he illuminated how blended learning can help us build capacity for deeper learning. By using the three-part axis of depth of knowledge (such as Bloom’s or Webb’s), stages of independence (students move dependent on direction from the teacher and toward self-directed learning), and acceleration (students start at different points and progress at different rates, meaning a student who is behind grade level may actually be learning at a much faster rate of learning), he provides a robust picture of what schools need to be able to do and how they can best do it using technology.

He explained how we can design schools so we turn to online learning for what it can do best and then direct teachers’ time toward guiding deeper learning. He made a distinction in the different types of online learning and outlined what they can and can’t do to support learning. He was very clear: Online learning (whether designed by a teacher, an online course, or a purchased product) can increase flexibility of pace and place. Adaptive software can provide much more rapid feedback to students than teachers ever could. However, the current state of the art of adaptive software is useful for the recall and comprehension levels of learning but not for higher levels of learning.1 That means we must support teachers to help students develop their higher level skills.

Actually applying these ideas will have huge implications. As we build out our capacity to integrate online learning into schools, we also need to build out our capacity for teachers to guide the cycle of learning (guiding/instructing, assessing, and feedback) for the higher levels of knowledge. Districts integrating blended learning may stumble if they aren’t using the depth of learning axis to guide their design.

Certainly, most districts that convert to competency education quickly recognize the need to upgrade their capacity to support higher level skills as they develop their Instruction and Assessment model including supporting teachers in calibrating their understanding of what is proficient. They soon realize that their instruction and/or assessments have been aimed primarily at recall and comprehension. Thus, educators begin to engage in their own professional development as well as school- or system-wide efforts to include or expand performance-based assessments. However, some schools can get stuck in the first year of implementation in the wilderness of standards, assuming that they have been written in a linear fashion they need to be taught exactly that way as well, bombarding their students with low skilled worksheets.

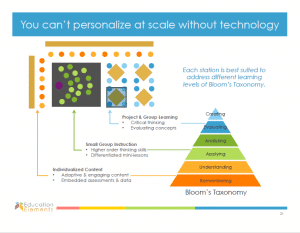

Kim’s visual (below) clarifies the relationships between students, teachers, online learning, and depth of knowledge. The graphic shows us how individualized content available in adaptive software is helpful in building the lowest level skills of understanding and remembering, how small group instruction can guide students in analyzing and applying the skills they are learning, and how project and group learning (think dialogue) can enable students to develop the highest levels of evaluating and creating.

The more I think about this, the more I think we might be talking about a continuum of teaching that ranges from guided learning for higher order skills and habits of learning (provided by a teacher either F2F or online, direct instruction (provided by a teacher, written materials, or through a video), targeted support (when students need some extra help, again provided through a teacher either F2F or online), and adaptive instruction (a software program focused on recall and comprehension of basic skills and concepts). Perhaps this isn’t a continuum at all…and we should simply be placing these different approaches within the matrix of depth of knowledge, stages of student agency, and acceleration. As I think this through, I realize that a continuum of assessing that takes into consideration the level of learning, the degree it is assessment-when-ready or time-based, and the mode of delivery (F2F, online, or product) also needs to be thought through.

I think it would be useful to do the same type of analysis regarding the stages of independent learning although I think using the concept of student agency would actually provide a more robust understanding of what we are seeking what we talk about students being college/career ready. As we look across types of learning opportunities (adaptive instruction, online curriculum or courses, in small groups, in project-based learning, or in the real-world), it is interesting to think about how they differ in the level of independence students have. However, we also want to ask: How effective are they in helping students build agency (having the skills to manage their own learning), providing opportunities for students to have voice (developing their own ideas in areas that have high interest to them as a process of building leadership skills), and in allowing choice in how students learn and demonstrate their learning?

The concept of acceleration or rate of progress still needs to be unpacked. At first glance it might seem easy as the simple equation of growth divided by amount of time. However, once you introduce depth of learning, students’ experiences in learning (the degree to which they have a growth mindset is shaped by the previous experiences learning and the range of learning opportunities available to them), and student agency, it suddenly becomes very complicated. We need to stay focused on progress as a function of growth and time so that we never let students fuddle along on their own without pushing ourselves to figure out what will help them succeed in their learning …while also continuing on our own “learney” to think more creatively about the metrics that will allow us to capture the rich dynamics of teaching and learning.

Sadly, this post reflects more of what I don’t know, but one thing I do know is that Kim’s triple axis of depth of learning, stages of student agency, and acceleration of learning is opening the door to discovery. Thanks, Anthony!!!!!

1. Beware: there are some pretty dismal products that have students move through online curriculum exactly as one might have to work one’s way through a textbook – with little personalization other than pace and place of learning).↩

See also: