Why New Zealand? A Primer on the NZ Education System

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the second article in the series Baskets of Knowledge from Aotearoa New Zealand, which highlights insights from a totally different education system about what is possible in transforming our education system. Read the first article here.

This is the second article in the series Baskets of Knowledge from Aotearoa New Zealand, which highlights insights from a totally different education system about what is possible in transforming our education system. Read the first article here.

As I planned my trip, I was constantly asked, “But why New Zealand? Are they better than we are?”

The simple answer is I went to New Zealand with the encouragement of Susan Patrick, CompetencyWorks co-founder and President/CEO of iNACOL. She visited several years ago and found that there were many lessons learned to be found there. However, the question of what makes an education system better than another one prompted an internal dialogue: “In what way might they be better? How do we judge the effectiveness of an education system?” It might be based on academic achievement scores but those don’t capture well-being, success in post-secondary employment, training or education, lifelong learning skills, or transferable skills such as problem-solving and communication. Perhaps we could look at the cost-effectiveness or satisfaction of teachers. Thus, I started my trip with an orientation of inquiry rather than analysis.

I am a believer in benchmarking against high performance to discover policies and practices that might bring improvements. However, I have not returned with solid recommendations for how we should replicate New Zealand. What I did find was that my expectations were lifted, my imagination sparked, and my understanding of our own education system clarified.

Below I provide a snapshot of New Zealand’s education system. In future articles, I’ll be looking more deeply at the system and the ways it can help us think about options for the American system.

The Basics

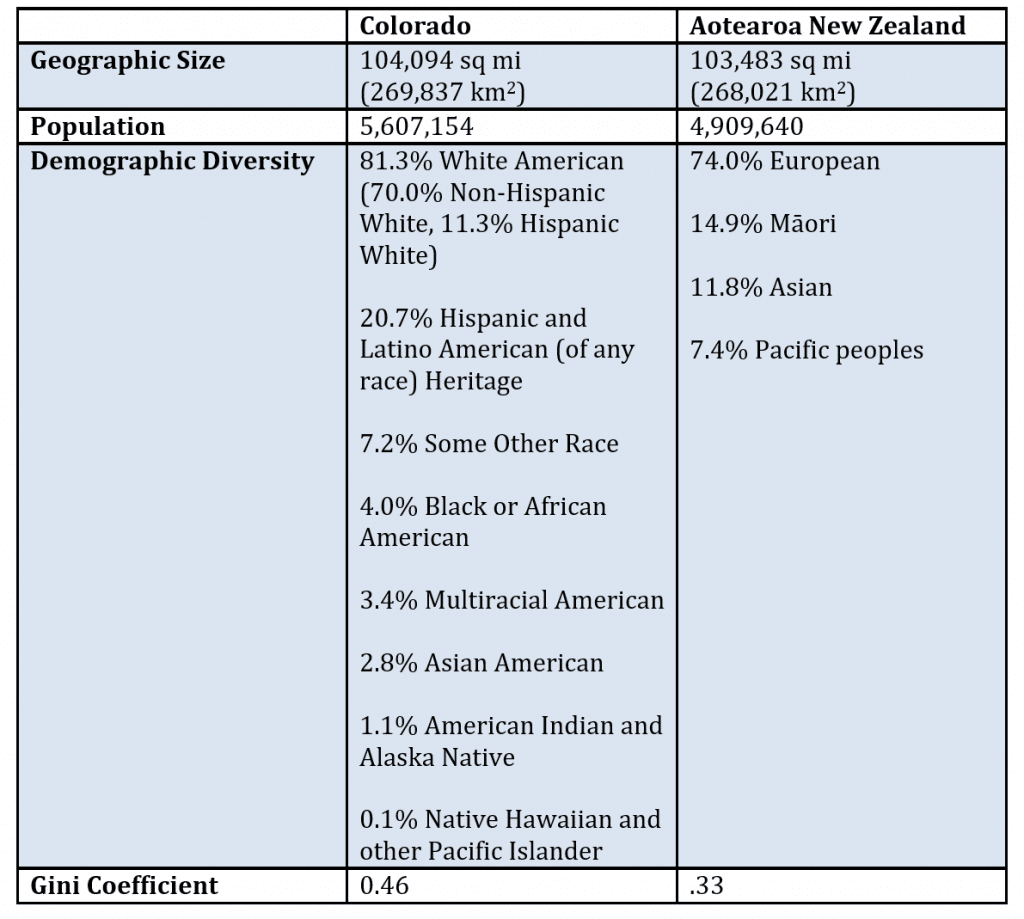

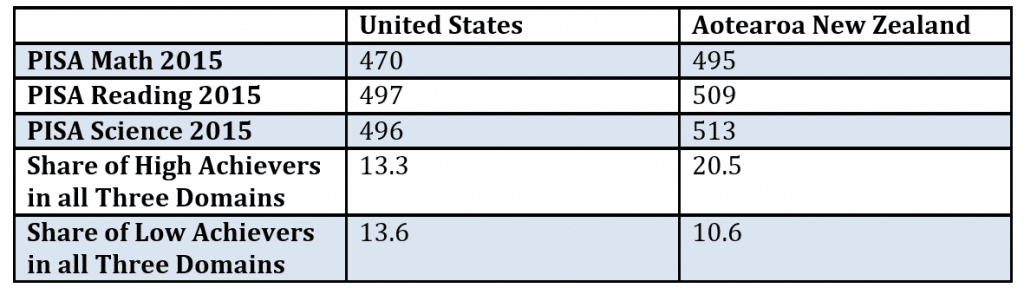

Aotearoa New Zealand is made up of two main islands, north and south, that are about the size of Colorado in terms of geography. Colorado’s population is about 10 percent larger than New Zealand’s. The percentage of what is referred to as European or Pākeha in New Zealand and White in the United States is also similar. However, the economic inequality, indicated by the Gini coefficient, in Colorado and the United States is larger. (Data from Wikipedia.)

Based on PISA, New Zealand performs consistently above the OECD average and above the United States in terms of academic achievement.

Based on PISA, New Zealand performs consistently above the OECD average and above the United States in terms of academic achievement.

However, as I spoke with educators in New Zealand about what is most important to them, I started to wonder how might we compare in terms of child well-being, lifelong learning (referred to as key competencies in NZ), and the development of transferable skills. How might students enjoy and engage in school activities in New Zealand compared to the United States?

However, as I spoke with educators in New Zealand about what is most important to them, I started to wonder how might we compare in terms of child well-being, lifelong learning (referred to as key competencies in NZ), and the development of transferable skills. How might students enjoy and engage in school activities in New Zealand compared to the United States?

The New Zealand Education System

Think about NZ as a model for state policy, not federal.

I found that it made much more sense to consider the education system of Aotearoa New Zealand as it might relate to state policy rather than federal policy. The size of our nation and the complexity of the multiple levels of governance made it difficult for me to translate across the two countries. Thus, I found it most helpful to consider ways in which insights can inform policy and practice at the state and local levels.

The New Zealand education system is organized around four major policies and five institutions.

Policies

Tomorrow’s Schools

In the mid-1990s, New Zealand passed a policy that flipped the education system on its head. Instead of being managed by the Department of Education, all 2,500 schools became autonomous with oversight by boards of trustees composed primarily of parents and community members. The first few years were bumpy as schools dealt with issues that had piled up under the previous bureaucratic culture, many of them facility related. As years have gone by and boards and principals learned through experience, some schools have begun to modernize their pedagogy and facilities in ways that are similar to the approaches described by student-centered or personalized learning in the United States. It is difficult to determine standard practice or even a sense of how schools might be clustered in terms of approaches in New Zealand because of this autonomy.

However, the schools do not have absolute autonomy. As described below, there are three other policies that influence schools.

Treaty of Waitangi

Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi, the founding document of New Zealand, was first signed in 1840 between a group of Māori leaders and representatives of the Queen of England. For over one hundred years it was ignored by the government of New Zealand. However, things began to change in the 1950s and 60s as Māori brought legal claims based on the Treaty. In the mid 1970s, a Waitangi Tribunal was established that honored and interpreted the Treaty. Over the decades, New Zealand has continued to embrace the Waitangi Treaty and seeks to become a bicultural nation where everyone is comfortable with both cultures – Pākeha (European) and Māori. Te reo Māori (the Māori language) is considered one of New Zealand’s three official languages (the third is NZ sign language). As part of this effort, the Ministry of Education has fully embraced the Waitangi Treaty and is seeking to create a bicultural education system. Thus, references to the Waitangi Treaty will be found in national and school documents.

Beginning in 2006 a revision of the national curriculum, the national policy relating to teaching and learning in English-medium schools, was introduced. A parallel document, Te Marautanga o Aotearoa, provides the policy for Māori-medium schools. The Māori version is an independent document and not simply a translation.

The term curriculum is used a bit differently than in the United States. It is a high-level and aspirational framework that describes vision, principles, values, key competencies, learning areas, and guidance for effective pedagogy. It also includes an overview of curriculum levels to provide a sense of how students are anticipated to move through eight curriculum levels over their thirteen years in school. (NZ uses 1-13 rather than K-12.)

The curriculum is an active document that provides guidance, not one that requires compliance. Almost every principal I interviewed referenced or actually pulled out a well-worn version of the NZ Curriculum to explain how and why they have designed their schools. Almost all had created their own language of learning. Sometimes schools were drawing directly from the national curriculum. Sometimes they had created something that was uniquely their own although very much aligned in spirit.

National Certificate of Educational Achievement

In New Zealand there isn’t a diploma just for seat-time. Under the National Certificate of Educational Achievement policy (NCEA) students earn certificates that indicate the level that they achieved. It’s possible, although unlikely, to stay in school all the way to Year 13 and still not get a certificate. Introduced in 2002, the NCEA has had several substantial modifications and is currently under review.

- Three levels of certificates: Students can earn a Level 1, Level 2 or Level 3 New Zealand Certificate of Educational Achievement during secondary school. There are three types of endorsements for earning credits: achievement, merit, and excellence. In U.S. terms we might think of as a de facto national grading policy. Although there is no requirement it be implemented in this way, schools tend to focus on students earning Level 1 in year 11, Level 2 in year 12, and Level 3 in year 13.

- Standards-based credits: How do students reach the certificate levels? They earn them by assessments (demonstrating learning) in achievement (academic) or unit (process) standards. These standards are a larger grain size than our academic standards. There is a concern that students “chase credits” as they have to earn a certain number if they want to be on track toward reaching Level 3 by end of Year 13. The system itself is quite flexible. Many of the secondary schools I visited were successfully innovating to create connection between the academic standards through interdisciplinary approaches.

- Dual system of moderated assessments: Schools can organize and students can choose to pursue either internal assessments developed within the school or an external examination developed by New Zealand Qualifications Authority (NZQA), International Baccalaureate, or the Cambridge system. Internal assessments, often designed to be performance tasks and in many cases authentic performance tasks, are moderated through sampling of student work by the NZQA. Over several decades the moderation mechanisms have been strengthened to ensure high levels of consistency between the different assessment processes.

- Certificates are aligned with both secondary and tertiary systems: Th three levels of NCEA are part of the qualification system managed by the NZQA that range from Level 1-6. The NZQA levels also overlap with the Ministry of Education’s curricular levels. Although the word “level” is used in several ways that can cause confusion (grade level such as Year 12; curricular level; NCEA level within the NZQA level), this system has created a more aligned set of expectations that stretch across secondary school and tertiary schools (universities, polytechnics, and private training providers).

Similar to the United States, students earn credits and leave secondary school with different levels of skills. However, the NZ system has a system that ensures consistency, transparency, and portability of its certificate of learning. For schools, districts and states considering proficiency-based credits, diplomas and transcripts, it is well worth studying the NCEA as there are multiple aspects that could help us make diplomas mean more than completing four years of high school.

Institutions

When Tomorrow’s Schools policy was passed, it redesigned how the education system was managed and monitored. There are five organizations that, through statute, have critical roles in the education system.

- Ministry of Education: The Ministry is responsible for education policy including the national curriculum, school funding, and opening and closing schools.

- Education Review Office: The ERO is responsible for quality assurance of schools and early childhood development providers through school reviews or audits. Schools receive a report with a recommendation for the next audit that range from 1-5 years.

- New Zealand Qualifications Authority: The NZQA is responsible for making sure certificates of learning are meaningful. They do so through managing the Qualifications Framework and the NCEA as well as independent quality assurance of non-university education and training providers. All tertiary providers must apply to have certificates of achievement approved ensuring that students or customers can be confident that the certificate will have value.

- New Zealand Council for Educational Research: NZCER is required through statute to carry out and disseminate education research and provide information and advice. In partnership with the University of Otago, NZCER manages the National Monitoring Study of Student Achievement. NMSSA monitors nationally representative samples of students in Years 4 and 8 in English-medium schools, using a combination of group-administered tasks (involving 2,000-4,000 students) and individual tasks (600-800 students). These assessments cover all learning areas of the New Zealand Curriculum over a four-year cycle, and address aspects of the key competencies.

- Education Council: Recently renamed the Teaching Council, this organization represents and registers teachers. It is responsible for developing a Code of Professional Responsibility. This document is an excellent example of the biculturalism that is taking root in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Although I have highlighted five key institutions, there are many other organizations that play critical roles in education including local iwi (tribal governments) and teacher unions including the PPTA and NZEI . Please note that New Zealand teachers are paid at similar levels to the United States and have also launched strikes in order to raise their salaries.

Summarizing the NZ Education System

Aotearoa New Zealand is a system built on trust and respect. They believe that their communities and educators can design and run schools that continually improve and respond to changes in order to provide effective education. To support and to safeguard this system of autonomous schools, there is an outline of what students should know and be able to do (the national curriculum), a moderated system of standards-based certificates indicating what students have actually learned, a quality assurance mechanism that audits schools and provides feedback to the board of trustees, and a national student monitoring process that determines performance of the overall system.

Although there is pride in their education system, no one I spoke with would claim it is a perfect system. There have been major implementation problems, including a concern that it takes too long to intervene in schools that have become dysfunctional. However, problems in the system are not a reason to discard the policies, only a call for adjustment and improvement. In fact, there are nineteen reviews underway on different aspects of the system including the NCEA, Tomorrow’s School, and the curriculum. This is an education system that at its core is reflective and dedicated to continuous improvement.

Read the Entire Series:

- Part 1 – Snaps from Aotearoa New Zealand

- Part 2 – Why New Zealand? A Primer on the NZ Education System

- Part 3 – Pt. England Primary: Making Sense of the New Zealand Curriculum

- Part 4 – Pt. England Primary: Creating a Culture of Respect, Belonging and Learning

- Part 5 – Pt. England Primary: Manaiakalani, The Hook from Heaven

- Part 6 – Pt. England Primary: Understanding Where Students Are

- Part 7 – Pt. England Primary: Gifting Language

- Part 8 – The Cherry or the Orchard

- Part 9 – Insights from Aotearoa New Zealand: Defining Lifelong Learning

- Part 10 – Insights from Aotearoa New Zealand: Key Competencies

- Part 11 – Insights from Aotearoa New Zealand: Credentialing Learning

- Part 12 – Insights from Aotearoa New Zealand: NCEA

- Part 13 – How Competency-Based is New Zealand?