Innovation in New Mexico: Project-Based Learning at ACE Leadership High School

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post about project-based learning is the fourth in a series of posts about innovation in New Mexico.

Founded in Albuquerque in 2010, ACE Leadership High School has always done education differently. Designed for students who have struggled, in some cases multiple times, to complete traditional high school programs, ACE prepares young people for the world of work in practical and creative ways. The school teaches core academic content through the lens of architecture, construction, and engineering (ACE). Students master academic content and standards by completing hands-on projects: think geometry via completing architectural renderings and kitchen renovations and math via designing and building roof trusses. ACE is a model for the field in using project-based learning to drive a competency-based pedagogical approach.

The school collaborates directly with industry professionals who lead courses, support projects and workshops, attend culminating student presentations, advise on needed industry skills, or host internships and mentorships. Many ACE graduates go on to join local construction professions. Recent examples include the Local 412 Plumbers and Pipefitters Apprenticeship program and the Central New Mexico Community College’s Electrical Lineworkers Pre-Apprenticeship program. One student reflected that ACE “set me up with internships to open my mind up to possible careers I can pursue.” Another student appreciated the “opportunity to be in working with the community” while also gaining job experience.

Project Teacher and Advisor Gillie Marquez explains how projects start with the end in mind: “What is the final product going to be, and what are the construction skills or industry skills that we want to cover? And then from there, I fill in academically what mathematics, what science is going to align and what skills they’ll actually use to build those products.”

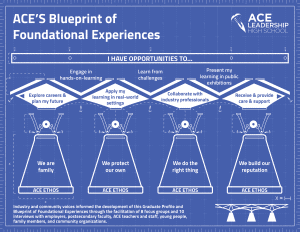

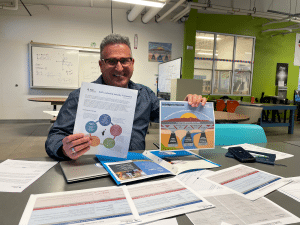

ACE’s Graduation Profile serves as the underpinning by defining what students should know once they finish high school and guiding the design of relevant, meaningful projects. Their Blueprint of Foundational Experiences spells out how ACE students build to the Graduate Profile goals and the foundational relationships and values that guide the community to support their success.

Making Learning More Engaging Through Smart Uses of Space and Time

When I visited ACE in February of 2024, I was immediately struck by the layout of the buildings. The main space is an open-concept design shop with a few partial partitions to define project spaces. At the far end of the open space are “clean rooms” with printers and computers behind closed doors. An outdoor area showcases the result of student projects, including an area to practice roofing installation and a small pond with benches. Signage with reminders of the ACE ethos kept ACE values visible and I felt engaged and welcomed. Casey Mason, Director of Curriculum and Assessment, shares that when school staff design projects, they ask: “What’s the thrilling learning? How are we going to hook these students? Because so much of our job is to motivate them, how do we make this meaningful and relevant?”

Some of New Mexico’s recent Innovation Zone advancements have expanded what ACE can do, but the school has approached learning through hands-on experiences from their very foundation.

The academic calendar begins with the building blocks of two interdisciplinary projects per trimester, six total per year. At the start of each trimester, teachers introduce the upcoming projects, offer detailed checklists to track progress, and explain what success will look like and what each student needs to demonstrate mastery. Multiple cross-curricular credits may be offered in projects that are co-taught by teachers of different disciplines. Students can earn up to two different credits in a project by demonstrating the learning outcomes aligned to each credit. An exhibition caps off the trimester, where students showcase the completed project and practice presenting to the community. At ACE, designing and building things IS the learning, and projects serve as both pedagogy and assessment. (The school also offers an accelerated 2-year evening program for undercredited students ages 17-22. These students complete one big project per trimester that addresses most if not all of the Common Core standards.) Advisories and electives are also part of the daily calendar, and, as I’ll explore in my next post, Wednesdays are dedicated to work-based learning.

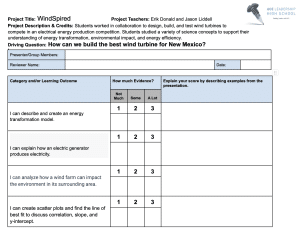

All projects begin with a driving question. A recent example is a project that addressed ELA, Civics, and US History standards to answer: How can we use city planning to design a better Albuquerque for all residents? Omkulthoom Qassem, Project Teacher and Advisor in ACE’s evening program, co-led this project: “Students were looking at our city, and they were seeing what kind of community issues in the US there are in the city. They were also looking at various unutilized or abandoned buildings within the city, what those buildings used to be, and why they shut down. How can those buildings be reutilized for new and renewed purposes through the lens of social determinants of health to better community wellbeing holistically?”

Showcasing Learning Through Community Exhibitions

I visited during a second trimester exhibition day in 2024 and could feel the excitement as community members and industry leaders arrived and got a folder, snack bag, and student-designed 3D-printed souvenir with the ACE logo. One group presented building plans and drawings in response to a project about redesigning prison facilities to reduce recidivism. Another group presented wind turbine designs and quantitative data from test runs, hoping to earn a spot to compete in a state-wide renewable energy design competition (ACE teams subsequently won first and second place and earned entry into the national competition). And a third demonstrated a debate around labor rights and how to protect workers’ rights as new companies move into the state.

At ACE, students practice communication skills and industry skills at the same time, and the entire school day and academic calendar align with the project timelines. Woven throughout the projects are opportunities to practice self-management and social-emotional skills. Adds Qassem: “Deadlines can be sometimes very challenging and life happens, so how do we create structures that can help them want to be accountable but also to work with them in building that skill in a low-risk environment?” In a student survey, a theme is that students enjoy learning through hands-on projects that help them visualize applications in dynamic and practical ways. One student said that the classes show you “how much the staff care about your future [and staff] help you in any way that they can to ensure that you perform well at school.”

To manage the workload for teachers and make student growth more visible over the years, ACE has begun repeating some foundational projects, which they call “anchor projects.” Example anchor projects include:

- “Simple Machines” where students create various desktop builds of simple machines culminating in a mousetrap car competition.

- “Deck the Sets,” a Humanities project that offers ELA and Art credits where students read a novel and then design and build a set and backdrop props to represent a “deleted scene” from the story.

Explains Mason: “We did an audit of all the projects we’ve taught the past couple of years and created some criteria around what makes a good anchor project.” Marquez likes that anchor projects make his workload more manageable but also remain flexible: “The nice part is we can tailor anchor projects to what these kids need and where they’re at now. We can sneak in [more complex] diagrams this time where we previously just did a simple algebraic calculation.”

In each trimester, ACE now offers a blend of anchor projects and new “pitch projects.” Mason likes that pitches give staff a chance to design new ideas: “We know we need to have some that are new each year to keep our industry focus fresh and adaptable to what our industry partners are saying.”

ACE shows that it’s possible to center learning-through-projects as a holistic curriculum driver. The way every moment of the school day at ACE is directed to project-based learning serves as a model for other schools tackling the pedagogy of competency-based education. In the next post, I’ll explore how ACE builds on its real-world projects through work-based learning.

Learn More

- ACE Leadership | High Quality Project-Based Learning

- Pairing Competency-Based Education with Project-Based Learning Makes for a Powerful Learning Experience

- Learning in a Supportive Community at Clark Street Community School

Explore the Innovation in New Mexico Series

- Innovation in New Mexico: The Origins of Community-Driven, Student-Centered Systems Change

- Innovation in New Mexico: Defining Local Visions of Graduate Success

- Innovations in New Mexico: Capstone Projects as a Path to Better Engage Students

Laurie Gagnon is the CompetencyWorks Program Director at the Aurora Institute. She leads the work of sharing promising practices shaping the future of K-12 personalized, competency-based education (CBE). Laurie lives in Somerville, MA with her partner, young son, and cat

Laurie Gagnon is the CompetencyWorks Program Director at the Aurora Institute. She leads the work of sharing promising practices shaping the future of K-12 personalized, competency-based education (CBE). Laurie lives in Somerville, MA with her partner, young son, and cat