Opportunities for State and Local Collaboration to Design New Accountability Models

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post is a follow up to our post, To Fully Realize Horizon Three, We Need New Accountability Systems, which is part of a series about Horizon Three (H3) learning exploring the ways we might fundamentally reimagine learning for the future ahead. This post is one of an ongoing series here on Aurora’s CompetencyWorks blog about rethinking accountability.

Imagine you are a community juror for senior Defenses of Learning at your local high school. You listen to the presentations of several seniors sharing the variety of ways that they have demonstrated the district’s Portrait of a Graduate competencies. They each showcase different artifacts from their academic classes, their internships, and their extracurricular activities ranging from sports to community volunteering. You ask each presenter follow up questions about what was most meaningful to them in their high school experience, where they have demonstrated the most growth, where they still struggle and how they think about improving. After each presentation, the group of jurors discuss the presentation and score the student using the competency criteria for presentation and reflection.

The students also take state-required large-scale standardized tests in English language arts and mathematics, but the community wants its learners to apply their learning and be ready for a dynamic world. The story told by testing data informs school improvement planning and accountability status, but it is only part of the story of learning.

What if the accountability system could capture a fuller picture of the robust learning going on at the school?

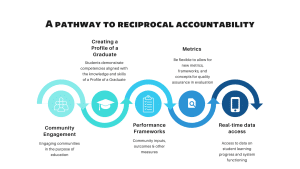

This post digs into three ways state and local entities can collaborate to create effective learner-centered, competency-based systems that can form the foundation and provide meaningful data for reimagined accountability systems.

- Engage Stakeholders in Creating a Shared Vision

- Invest in Calibration and Feedback on Local Assessment Systems

- Design and Pilot Reciprocal Accountability Models

These three moves are not necessarily new, but how might states and their local districts collaborate to bring these areas of work together in pursuit of an education system that prepares each learner for a future with meaningful possibilities?

In partnership with leaders in the field, we invite you to envision potential structures for new accountability models that better align to learner-centered education and what we know about how humans learn. We invite you to be a part in laying the groundwork to implement those ideas and models, one step at a time.

Why Rethink Accountability?: A Recap

Current accountability models focus on compliance, with schools waiting passively for their standardized testing data to know if they did well or will be identified for intervention. Schools are encouraged to “raise test scores,” but often struggle to know how to make effective changes. By contrast, the Defense of Learning vignette we opened with comes from a system that encourages innovation and local community participation, aligning with learners’ needs and strengths, and communicating a broader vision of success. A reimagined, aligned accountability model might share responsibility for both identifying a broader range of educational outcomes and promoting continuous improvement to achieve that vision of success.

The term reciprocal accountability, coined by the late Harvard Professor Richard Elmore, refers to a system where “every increment of performance I demand from you, I have an equal responsibility to provide you with the capacity to meet that expectation. Likewise, for every investment you make in my skill and knowledge, I have a reciprocal responsibility to demonstrate some new increment in performance.” Reciprocal accountability ensures all stakeholders, including students, educators, and governments, practice mutual responsibility within a system, taking responsibility for their roles and actions from setting and achieving goals to providing the resources, capacity, and conditions to make it possible.

Engage Stakeholders in Creating a Shared Vision

Building a shared vision, both at the state and local levels shifts the the power dynamics to invite more people in multiple roles – from students and families, to community and business partners, to the educators within schools and districts, to policy makers and state leaders – to contribute to something bigger than than what they can do working alone. A shared vision often stems from a Portrait of a Learner or Graduate (PoG), which names the competencies a community believes young people need to thrive in life beyond a K-12 system. A PoG process cultivates relationships that become the foundation for how that vision shows up in the learning process. Rather than a static set of academic standards to comply with, working from a PoG shifts to a collaborative dynamic of support and responsibility.

Local communities across the country and at least nineteen states are engaging communities in PoG processes and then using the resulting vision to reimagine the opportunities for learning. In Wyoming, for example, the Profile of a Graduate process and Governor’s Reimagining and Innovating the Delivery of Education (RIDE) initiative engaged in statewide surveys and listening sessions in more than a dozen communities. The outcomes now form the foundation for districts to create Wyoming’s Future of Learning.

Invest in Local Assessment Calibration Systems

Opening space for districts and states to lead their own process for achieving a PoG – which could be a state PoG or a local PoG – invites new ways of verifying the evidence of student learning. A local assessment system enables the community to determine whether learners have met those expectations. Key learning system elements integrate to create a cycle that supports a valid and reliable learning system:

Opening space for districts and states to lead their own process for achieving a PoG – which could be a state PoG or a local PoG – invites new ways of verifying the evidence of student learning. A local assessment system enables the community to determine whether learners have met those expectations. Key learning system elements integrate to create a cycle that supports a valid and reliable learning system:

- Competencies provide clear learning targets tied to the PoG and state standards.

- A Curriculum Roadmap identifies learning opportunities within and beyond the classroom

- An Instruction Model designs practice to support learning, personalization, and feedback.

- An Assessment System offers multiple opportunities to demonstrate learning when students are ready.

- Calibration processes to collaboratively analyze student work examples provide evidence of validity and reliability of learning the competencies.

Competency frameworks that detail the expectations for student learning with performance indicators that are explicit, transparent, and measurable provide an essential foundation for a local assessment system. We see hope in initiatives such as Skills for the Future, which aim to develop measures for PoG skills that are externally validated. However, the most effective systems, just as is true for the most effective learning experiences, are intrinsically-driven, thus, even if external assessments shift to focus on PoG skills they ideally will work in concert with strong, local assessments.

The NH Performance Assessment for Competency Education was an early model to learn from, with a balance of local and cross-school performance assessment, validated periodically by state testing. The long-standing New York Performance Standards Consortium uses a process of moderation for participating schools to get feedback on the work students produce. These examples are supported by building the assessment literacy capacity of staff in order for them to know where students are in their learning separate from external assessments. External assessments, such as the large-scale standardized state tests may still have a role, but rather than the driver of accountability decisions, they become a checkpoint for triangulation to give feedback for the local system.

Design and Pilot Reciprocal Accountability Models

The two recommendations above provide needed support and encouragement for engaging local communities to create a shared vision and putting that into practice in the learning environment through the design of curriculum, instruction, and assessment. States can also help local communities who are ready to pilot new accountability models by supporting and enabling new approaches through offering waivers from state accountability systems or other allowances for flexibility.

Local systems do not need to be one-size-fits-all. They can be responsive to local needs and cultures. In Minnesota, the Pillsbury United Communities (PUC)’s Office of Public Charter Schools (PUC-OPCS) used an inclusive process to create its Equity Framework. The framework, recognized by the Minnesota legislature, provides a comprehensive picture of school quality and impact which includes a more diverse set of whole-child-centered school performance measures than those found in traditional accountability systems. The Massachusetts Consortium for Innovative Education Assessment (MCIEA) uses School Quality Measures and performance assessment as the cornerstones for creating “a fair and effective accountability system that offers a dynamic picture of student learning and school quality.”

With greater variation in approaches by design, we need to pay close attention to who is accessing deeper learning and ensure systems hold high expectations for learners, even if they learn via different pathways. A robust research and development (R&D) agenda, built in partnership with the research community, states, and local systems, could focus on developing new methods for validation and comparability to proactively and transparently identify disparities in access and outcomes and enable course correction where needed. Even if districts are not ready to pilot new accountability models, leaders can cultivate a mindset of learning and continuous improvement through ongoing R&D efforts.

Similarly to calibration of PoG competencies, the evaluation and calibration of the outcomes and impact of locally-defined accountability measures might include facilitated communities of practice where members provide feedback on both student outcomes, inputs, and processes in the learning community. They might answer questions like “Are students achieving the expectations for learning at a level that allows them to thrive?” At the systems level, feedback could focus on creating a culture of continuous improvement, asking: “What practices, structures, and cultures support student learning and which hinder it?” Kentucky’s United We Learn – an ongoing effort aiming to “launch an accountability system that is meaningful and useful to all our learners” – includes the idea of peer districts playing a role in support and feedback in their new system. States can support these feedback and validation mechanisms for local systems to ensure that new accountability systems are equitable, valid, and result in continuous improvement at the school and system level.

A key mindset shift in realizing new accountability models – actually creating and implementing them, not just imagining them – lies in moving from systems of compliance to systems of learning. The currently rigid status quo assessment and accountability systems hamper innovation. Creating more autonomy – with reimagined accountability systems – can help us learn what is possible in the future of learning.

Stay tuned for future posts on new models for accountability, including upcoming posts from Kentucky and learn more by revisiting past posts, such as this recent post about the process of competency calibration.

Learn More

- To Fully Realize Horizon Three, We Need New Accountability Systems

- Calibration Supports Quality for Flexible, Competency-Based Systems

- Grounded in Their Competency Model, Boston Day and Evening Academy Evolves and Sustains

Laurie Gagnon is the CompetencyWorks Program Director at the Aurora Institute. She leads the work of sharing promising practices shaping the future of K-12 personalized, competency-based education (CBE). While working on the Quality Performance Assessment program at the Center for Collaborative Education, Laurie led many calibration and performance assessment literacy sessions.

Virgel Hammonds is a nationally recognized leader in education innovation and the CEO of the Aurora Institute. With over two decades of experience, he has worked alongside educators, policymakers, and communities to create learner-centered systems. Previously, he served as Chief Learning Officer at KnowledgeWorks, superintendent of RSU 2 in Maine, and a high school principal at Lindsay Unified in California, where he helped implement a personalized learning model.

Virgel Hammonds is a nationally recognized leader in education innovation and the CEO of the Aurora Institute. With over two decades of experience, he has worked alongside educators, policymakers, and communities to create learner-centered systems. Previously, he served as Chief Learning Officer at KnowledgeWorks, superintendent of RSU 2 in Maine, and a high school principal at Lindsay Unified in California, where he helped implement a personalized learning model.