Key Findings: Science of Learning and Development

CompetencyWorks Blog

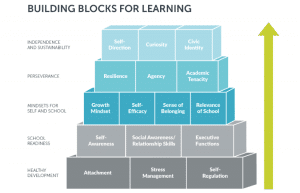

Although the high level findings of the science of learning often seem like common sense, the interplay between the different domains of research isn’t as simple. And we know that the education system is full of practices that are not only misaligned with the science of learning – they may actually be inhibiting and, for some students, even harmful. I’ve read two papers that support Turnaround for Children’s Building Blocks for Learning recently:

- Malleability, plasticity, and individuality: How children learn and develop in context and

- Drivers of human development: How relationships and context shape learning and development.

The papers have synthesized the research findings of the science of learning and development – something that has rarely been done until now. They are not papers one gets to just skim through and absorb. In fact, I had to open up the dictionary several times in order to understand some of the findings.

I’ve copied the key findings from Malleability, plasticity, and individuality here to make it easy for you to access. I’m wondering as you read through this list: To what degree do your policies, districts, and schools reflect these findings? What would it take to align them? A few of my initial reactions (and I’m assuming I’m going to easily end up reading this paper ten times) include:

- We can and should design to enhance relationships;

- Common language or frameworks can help us talk about where students are in their development (academically, emotionally, and physically) and the implications for how educators support them in their learning; and

- There isn’t one way to implement the sciences of learning. It is going to be equally or more important for developing professional judgment than it is for creating a best practice or best model.

Science of Learning and Development—Key Findings

1. Human development depends upon the ongoing, reciprocal relations between individuals’ genetics, biology, relationships, and cultural and contextual influences.

- Human development occurs within nested, interlinked micro- and macro-ecological systems that provide both risks and assets to development and affect development both directly and indirectly.

- Epigenetic adaptation is the biological process through which these reciprocal individual-context relations create qualitative changes to the expression of our genetic makeup over time, both within and across generations.

- Genes are chemical “followers,” not the prime movers, in developmental processes; their expression at the biological level is determined by contextual influences.

- The development of the brain begins prenatally and continues in one developmental continuum well into young adulthood. Opportunities for change, intervention, and growth exist across the developmental continuum, with particularly sensitive periods in both early childhood and adolescence.

- Developmental systems theory and associated dynamic systems mathematical models provide a holistic, contextualized framework within which to integrate diverse, field-specific scientific knowledge, enabling a deeper understanding of the developing brain and whole child in context.

- Intergenerational transmission is rooted in biological and social processes that begin before a child is born. Preventing the negative impacts of adversity can prevent the transmission of adversity and its many risks to development to future generations. Conversely, building individual and environmental assets can promote the intergenerational transfer of adaptive systems and opportunities.

2. Each individual’s development is a dynamic progression over time.

- The human brain is a complex, self-organizing system.

- Neural plasticity and malleability enable the brain to continually adapt in response to experience, which serves as a “stressor” to brain growth across development.

- Each individual’s development is nonlinear; has its own unique pacing and range; features multiple diverse developmental pathways; moves from simplicity to complexity over time; and includes patterns of performance that are both variable and stable.

- Whole child development requires the integration and interconnectivity—both anatomically and functionally—of affective, cognitive, social, and emotional processes. Though these processes—particularly cognition and emotion—have historically been dichotomized, they are inextricably linked, co-organizing and fueling all human thought and behavior.

- The development of complex dynamic skills does not occur in isolation; it requires the layering and integration of prerequisite skills and domain-specific knowledge, as well as the influence of contextual factors.

- Inter- and intra-individual variability in skill construction and performance—both of which are highly responsive to contextual influences and supports—is the norm. The optimization of development requires an understanding of both stability and variability in growth and performance.

3. The human relationship is a primary process through which biological and contextual factors mutually reinforce each other.

- The human relationship is an integrated network of enduring emotional ties, mental representations, and behaviors that connect people over time and space.

- Attachment patterns are formed through shared experiences of co-regulation, attunement, mis-attunement, and re-attunement. Though important in shaping future relationship patterns, early patterns remain open to change as children re-interpret, appraise, and re-appraise past experiences in light of new ones.

- Developmentally positive relationships are foundational to healthy development, creating qualitative changes to a child’s genetic makeup and establishing individual pathways that serve as a foundation for lifelong learning and adaptation.

- Developmentally positive relationships are characterized by attunement, co-regulation, consistency, and a caregiver’s ability to accurately perceive and respond to a child’s internal state. These types of relationships align with a child’s social-historical life space and provide protection, emotional security, knowledge, and scaffolding to develop age-appropriate skills.

- The establishment of developmentally positive relationships can be intentionally integrated into the design of early care and educational settings, practices, and interventions.

4. All children are vulnerable. In addition to risks and adversities, micro- and macro-ecologies provide assets that foster resilience and accelerate healthy development and learning.

- Children’s development is nested within micro-ecological contexts (e.g., families, peers, schools, communities, neighborhoods) as well as macro-ecological contexts (e.g., economic and cultural systems). These contexts encompass relationships, environments, and societal structures.

- Adversity, through the biological process of stress, exerts profound effects on development, behavior, learning, and health.

- Resilience is a common phenomenon wherein promotive internal and external systems integrate to facilitate the potential for positive outcomes, even in the face of significant adversity. As no two children draw from the same combination of experiences and supportive resources, resilience pathways are diverse, and yet can lead to equally viable and complex adaptation and, ultimately, well-being and thriving.

- Environments and societal structures include the differential allocation of assets and risks, as well as the impact of differing belief systems about roles, talents, learning, and other factors viewed as driving personal success. While factors such as poverty and institutional racism makes poor outcomes more likely, family and community assets must be recognized, as they can protect children from short- and long-term negative consequences.

- Adult buffering can prevent and/or reduce unhealthy stress responses and the resulting negative consequences for children. As such, building and supporting adult capacities are critically important priorities.

- Early care and educational settings that provide developmentally rich relationships and experiences can buffer the effects of stress and trauma, promote resilience, and foster healthy development. Meanwhile, developmentally unsuitable and/or culturally incongruent contexts can exacerbate stress, hinder the reinforcement of foundational competencies, and impel maladaptive behaviors.

5. Students are active agents in their own learning, with multiple neural, relational, experiential, and contextual processes converging to produce their unique developmental range and performance. This holistic, dynamic understanding of learning has important implications for the design of personalized teaching and learning environments that can support the development of the whole child.

- Diverse scientific fields converge to describe the holistic, complex, dynamic, contextualized processes that describe how children develop as learners.

- A powerful organizing metaphor through which to understand the dynamic interrelationships governing children’s development and knowledge and skill construction is that of the “constructive web.”

- Key factors that affect learning are internal attributes (including prior knowledge and experiences; well-developed habits, skills, and mindsets; and motivational and metacognitive competencies) and critical elements of the learning environment (including positive developmental relationships; environmental conditions for learning; cultural responsiveness; and rigorous, evidence-based instructional and curricular design).

- Foundational skills such as self-regulation, executive functions, and growth mindset lay the groundwork for the acquisition of habits skills and mindsets including both higher-order skills (e.g., agency, self-direction) and domain-specific knowledge.

- Motivation and metacognition are important, interrelated skills for effective learning. These competencies enable and encourage students to initiate and persist in tasks, recognize patterns, develop self-efficacy, evaluate their own learning strategies, invest adequate mental effort to succeed, and intentionally transfer knowledge and skills to solve increasingly complex problems.

- Instructional and curricular design can optimize learning. Together, well-scaffolded, engaging, relevant, and rigorous content; personalized contextual supports in multiple modalities; and evidence-based, mastery-oriented pedagogies embedded in well-designed, interdisciplinary projects can balance what students already know with what they need and want to know.

- Interpersonal and environmental conditions for learning (CFL) impact learning processes both directly and indirectly through their effects on cognition (e.g., cognitive load), student and teacher stress, and the relational dimensions of learning (e.g., attunement, trust). High-support conditions that recognize students’ individual starting points and strengths can facilitate deeper learning while increasing developmental range, performance, and mastery.

- Culture is a critical component of context. Cultural competence and responsiveness can address the impacts of institutionalized racism, discrimination, and inequality; promote the development of positive mindsets and behaviors; and build self-efficacy in all students, particularly those from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

- Skill development occurs in all ecologies, cultures, and social fields. Next to the family, early care and education settings are the most important social contexts in which early development unfolds.

- Research and development (R&D) efforts can be enriched, and progress accelerated, by employing dynamic systems analysis techniques and rapid-cycle improvement science methodologies to identify positive variation in developmental pathways and apply this knowledge at scale.

- The design of education and other child-serving systems—and surrounding policy environments—cannot bet on the resilience of children alone. Rather, such systems must capitalize on the opportunities presented by the translation of developmental science to the design of contexts and practices, therein supporting a fully personalized approach to whole child development and the expression of human potential.

- Dramatic improvements in outcomes and equity depend on public and political will. Sound policies to foster whole child development and practice must be grounded in rigorous science; implemented with quality; measured with an understanding of the formative progression of individual development; and adopted at scale, with cultural competence and equitable outcomes as explicit goals (Moore, 2015; Slavich & Cole, 2013).