Bringing Critical Design Pillars into Practice

Education Domain Blog

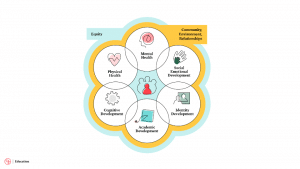

The following is a third excerpt and transcript of the Aurora Institute 2019 Symposium opening keynote address, delivered by Chan Zuckerberg Director of Whole Child Development Dr. Brooke Stafford-Brizard. In the address, titled Broadening the Definition of Student Success: A Spotlight on Mental Health, she dives deeply into what it could look like to integrate mental health, as one pillar of whole-child development, into schools. Part 1 and part 2 build the case for whole-child personalization in schools with emphasis on mental health. Here in part 3, she fuses learnings about design with practice.

I want to focus on three core pillars of design that are critical in learning environments: skill development, relationships, and environment. We’re going to go deeper in this coming week in all of these spaces. The Turnaround for Children team is going to be presenting a number of times. The DC Public Schools team is going to share their story about how they’ve leveraged brain science to focus on personalization. There will be sessions focused on some of these specific skills and mindsets that I’ve spoken about, like belonging, but I want to leave you with some images and some concrete examples of what it looks like to bring these design pillars to practice.

When it comes to skill development, I want to focus on a partner that we have in DC Public Schools, Van Ness Elementary, and Cynthia Robinson-Rivers is a principal who has been dedicated to integrating the science of learning and development into her school. She’s learned some really important lessons along the way. One, when it comes to skill development for students, that has to be grounded in learning science. So many of us have what we would call a peace corner or a safe space in our classrooms. Cynthia found that just creating that resource and giving students the opportunity to go there, to re-engage, to de-escalate, or to become more present wasn’t sufficient because it’s a skill set that that student needs to learn and often needs to learn through co-regulation and relationship. So when Cynthia started to really focus on the principles of learning science, like the opportunity for practice, the opportunity for feedback, and the ongoing application based on that feedback, she saw dramatic difference in the way students could access and use these spaces.

Cynthia also focused deeply on personalization. One of the strategies that we tend to use in schools to think about presence and de-escalation is mindfulness or meditation. That works for some students, but not for all. Some students need a more active strategy, like tossing a ball or music therapy and engaging in a drum circle. Closing their eyes and meditating or being mindful is not the right strategy for all students. So, she’s been able to think about how to differentiate there.

Cynthia and the Van Ness team have also thought deeply about how to use every minute of the school day. If they see students who need more help with their emotional well-being, they have adults who are dedicated to those students and are using the minutes of recess to engage with that student and any time that they can find to really focus on their well-being. And if they also see students who need that support, across the adult community, they increase the number of what they call rituals for love and connection that that student gets. But it’s not left to chance. It’s intentional, and it’s led by that team. Those connections are absolutely critical for students to make, and that’s another area where we had to think about personalization because students connect to us in very different ways. We all have different attachment styles. One student might need to be brought close and feel that connection. But that might not be what another student needs. In fact, it might trigger them. They might need to feel that support through demonstration of their independence and knowing that you’re there. So even the way that we connect with students and form those attachments need to be deeply mindful and understanding of what works for them and where they’re coming from.

The second pillar is relationships. You saw me speak to this deeply in the work of Valor and how they built those relationships across that community. I also want to focus on another core partner that we have, the Summit Learning program. Summit and the team focus on providing support to hundreds of schools to implement a model that focuses on project-based learning, self-directed learning time, and mentoring. Our technology team at CZI supports the implementation of a platform that allows for that to happen and reinforces [it]. We can only continuously improve that work if we’re listening to teachers, and in a partnership with that team, we’re hearing from them constantly. One of the things we’re hearing is how important mentoring is, and that that dedicated time that intentional space to build relationships with students is something that they knew would matter. But they also acknowledge that unless it’s intentionally focused on, unless that time is carved out, it’s not going to happen. Summit and the team also leverage technology, and that’s a critical tool in this space. We’re mindful that this has to be done strategically, and in Summit’s case, the platform that students can use where they can track their progress, gain awareness about themselves, and where the mentors can gain that same access to the knowledge about the student—that drives their face-to-face time together. That’s content and fuel that helps them better understand each other and how that mentor can support the student.

The final area that I want to focus on is environment. The physical environment around students is a critical space for supporting their mental health and well-being. The Science and Math Institute is a partner school that we have in Tacoma, Washington. It’s a district high school that is embedded in a zoo and aquarium. Those students are not just able to use that cultural institution as a classroom, but they’re also acting as docents for that museum. That gives some connection to their community and the purpose that they have as members of that community.

The final area that I want to focus on is environment. The physical environment around students is a critical space for supporting their mental health and well-being. The Science and Math Institute is a partner school that we have in Tacoma, Washington. It’s a district high school that is embedded in a zoo and aquarium. Those students are not just able to use that cultural institution as a classroom, but they’re also acting as docents for that museum. That gives some connection to their community and the purpose that they have as members of that community.

Codman Academy is a charter school in Boston. They have restructured their entire physical environment to focus on  being trauma-informed. What you see here in this picture on the bottom left is kind of embedding elements of nature in the walls, and it’s kind of it’s across all their classrooms. You also see trauma-informed colors. Those cool colors, of the blue and the green and the cream-colored walls, have been proven to calm students, versus colors like yellow and red and orange that escalate and don’t have that calming effect. They’re mindful about how they use color. You’ll also see that they’ve gotten rid of institutional hallways. There are nooks and corners and crannies that make that space feel more like home.

being trauma-informed. What you see here in this picture on the bottom left is kind of embedding elements of nature in the walls, and it’s kind of it’s across all their classrooms. You also see trauma-informed colors. Those cool colors, of the blue and the green and the cream-colored walls, have been proven to calm students, versus colors like yellow and red and orange that escalate and don’t have that calming effect. They’re mindful about how they use color. You’ll also see that they’ve gotten rid of institutional hallways. There are nooks and corners and crannies that make that space feel more like home.

Montessori for All is a school that has taken that sense of home to an entirely different level. Their classrooms are actually little houses. They have porches and gardens. Students have that sense of safety, comfort, and belonging that you have in a home.

Montessori for All is a school that has taken that sense of home to an entirely different level. Their classrooms are actually little houses. They have porches and gardens. Students have that sense of safety, comfort, and belonging that you have in a home.

I mentioned all of the learnings that we’re developing in partnership with our grantees and other partners in the field, is we’re leveraging those. We’re leveraging the learnings from our partners who synthesize and codify the science. We’re also leveraging learnings from practitioners who’ve been innovating in schools and classrooms for years. We’re using those to drive our investments to bring stronger applied practice grounded in the science of learning and development and support the development of more holistic learning environments. We don’t believe this is possible unless we rethink partnership. Our schools and our system were created long before the sciences of human development and learning emerged. But a lot of it hasn’t changed. We haven’t found ways to route those learnings into the structures in the system and the design of schools.

What would that look like?

We believe we can only get there when we think about partnership across this framework. Our work is really grounded in the evolution of the research–practice partnership. That means when we  think about researchers, we want educational researchers right there at the table, but we also think about important partnerships with public health researchers, neuroscientists, social psychologists and how they can connect with each other. With practitioners, we’re deeply focused on classroom teachers, school leaders, and district leaders, as core partners in this work, but we also think of practitioners as clinicians, social workers, pediatricians, and community organizers. We want to break down those siloed fields and think about how all of those things integrate in the child and the adolescent and focus on how we can build innovation in response to those partnerships.

think about researchers, we want educational researchers right there at the table, but we also think about important partnerships with public health researchers, neuroscientists, social psychologists and how they can connect with each other. With practitioners, we’re deeply focused on classroom teachers, school leaders, and district leaders, as core partners in this work, but we also think of practitioners as clinicians, social workers, pediatricians, and community organizers. We want to break down those siloed fields and think about how all of those things integrate in the child and the adolescent and focus on how we can build innovation in response to those partnerships.

We can’t address huge issues, like serious trauma in our schools, without having clinical psychologists and social workers at the table—not just partnering but designing with us. We can’t address things like sense of belonging in our students of color if we’re not partnering with experts in racial and ethnic identity. We believe those types of partnerships will drive the work of education, and we’re committed to that.

Some of you are well on your way in this journey, and some of you are just getting started. But I think one thing, and Susan noted this a number of times, is that there’s no one solution to this work. What we’ve learned from partners like Valor and Van Ness is that they’re very different ways of going about this. Valor was founded with that skill set that was complementary in mind—a traditional school leader cofounding a school with a clinical expert. I don’t know of any other identical twins in the field who have perfect complementary skill sets to create a whole-child environment. So that’s not the one solution. Cynthia took a very different approach at Van Ness. She immersed herself in the science. She built book studies and book groups to help build the capacity of her adults. She partnered with an organization called Transcend that translates the science into practice and supports them in that space. She thought about how things like discipline, and her policies and procedures when it came to that, needed to be grounded in human development and brain science. And so she’s created those partnerships to ensure that the way she disciplines her students doesn’t contradict or impact their mental health and wellness.

Regardless of the path that you’re taking in this space, they’re three key messages I want to leave you with. One important component of doing this work is conviction. There isn’t one partner that we have in the field who didn’t start their work with their adults. That means shifting mindsets and creating that sense of understanding across the adult community. This is critical and just as important and drives academic development—and that’s from your classroom teacher up to your board member.

It’s not just the mindset. It’s ensuring that teachers have the capacity-building that they need to learn skills that were not part of their education preparation programs. That means bringing in experts: universities, nonprofits. It also means relying on deep expertise that you have within your districts, in your organizations: special education teams, clinical teams, social workers, school nurses. They have skill sets that can build adult capacity that are not just important for a subset of students through an intervention lens but could impact the design and success of entire schools.

The second takeaway I want to drive home is collaboration. None of our partners were able to do this alone. They had to think about the expertise and skill sets that they could access outside of the traditional paradigm of education. That doesn’t mean having a consultant come in at the beginning and give some guidance and maybe periodically check in. It’s authentically resetting the table of partnership to really reflect the holistic development of students with deep expertise. That’s part of those spaces.

The final note is creativity. None of this will be possible if we don’t access and allocate resources. We’re very encouraged by funding that we’re seeing at the federal grant program level and across states. There are significant resources that are being allocated toward mental health in schools. There are also resources within your own district. A number of the schools that we partner with have been able to leverage those school psychologists, those social workers to, again, impact the entire environment, and not just work with subsets of students. Getting creative about the resources that are within your district, in your organization, is just as critical.

I’ve been in this work for over 20 years. And every day, I’m very mindful of the massive amount of work that we need to do to reach all students. I’m also incredibly optimistic because the hunger that we’re seeing from students, from families, from educators to focus on that more holistic approach to education is real, and it’s reinforced by the science. I really believe with those authentic innovative partnerships that we can reimagine what school can look like for all of our students through a more holistic lens.

I feel pretty strongly that the future of learning is actually grounded in why I came to this work and why many of us came to this work. It’s to support the healthy, holistic development of our children.

Thank you so much for listening.

Dr. Brooke Stafford-Brizard is Director of Whole Child Development at the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Continue to watch this space for more from her 2019 Aurora Institute Symposium keynote address. See more highlights from the entire conference on this page.