Flushing International’s Three Learning Outcomes: Habits, Language and Academic Skills

Education Domain Blog

This post first appeared on CompetencyWorks on July 26, 2016.

This is the fourth post of my Mastering Mastery-Based Learning in NYC tour. Start with the first post on NYC Big Takeaways and then read about NYC’s Mastery Collaborative and The Young Woman’s Leadership School of Astoria.

Magic. I think magic happens at the International Network of Public Schools (INPS). How else can they take a group of ninth graders who have newly arrived to the United States – with a range of English skills and academic skills – and within four years have them speaking and writing English, passing the New York Regents with their archaic focus on content (they require students to learn and regurgitate content knowledge about the Byzantine empire in order to graduate), and completing all the high school credits?

So why would an International School that is already performing magic with students want to become mastery-based? Flushing International’s principal Lara Evangelista was perfectly clear on that point. “We started along the path toward mastery-based learning when we began to ask ourselves why we assess,” she said. “Why do we grade? We realized that every teacher did it differently. The transparency and intentionality of mastery-based learning makes a huge difference for our teachers and our students. Our teachers are much more intentional about what they want to achieve in their classrooms. It has also opened up the door to rich conversations about what is important for students to learn, pedagogy, and the instructional strategies we are using. For students, the transparency is empowering and motivating. They are more engaged in taking responsibility for their own education than ever before.”

How Mastery-Based Learning is Making A Difference

The value to teachers was very clear. Math teacher Rosmery Milczewski explained that she was unsure at first, as she wasn’t familiar with mastery-based learning. “The thing that convinced me is that in the traditional grading systems, when a student would come and ask how they could do better in a class, all I could really say was study more,” she explained. “The grades didn’t guide me as a teacher. There was no way to help students improve. With mastery-based grading, we talk about specific learning outcomes. I know exactly how to help students and they know exactly where their strengths and weaknesses are.”

Science teacher Jordan Wolf explained how mastery-based learning helps on a daily basis with, “It only makes sense. If we don’t let students know what the expectations are, then we have to explain it by giving lots of comments as feedback. If we just let them know up front, then they can work harder to get it right the first time around.”

Several teachers remarked that mastery-based learning has both improved project-based learning and increased the value of it within the school. Assistant Principal Kevin Hesseltine noted, “Our projects are teacher-designed. The intentionality has made a huge difference on the quality of our project-based learning.” Wolf explained, “The question of how you judge what mastery is has made a huge difference for me. I don’t use quizzes any more. I would rather spend a day working on project with students than designing and grading a quiz.”

Evangelista explained that there is no expectation that every discipline team or every teacher be at same place at the same time. They are all learning more about mastery-based learning and how to better support students. To support teachers in this process, the school runs a RFP process every year. Teams develop proposals that are aligned with the schoolwide goals. They have the year to implement and present their work at a retreat in June. Evangelista explained, “Our teachers are inspiring each other. The RFP process helped us allow teams to work together based on where they were and what they thought needed to be the next step while also helping us push the work together into a schoolwide strategy.” At the staff retreat this year, Flushing International will be using the rubric developed by Brian Stack at Sanborn Regional High School to reflect on their progress in implementing mastery-based learning.

Starting With A Strong Foundation

Many schools I visit are not intentional about their school culture and pedagogy, and only discover that they need to tend carefully to culture and articulate a theory of teaching and learning after they have spent several years doing competency education. Not so at Flushing International. The school culture is organized around twelve principles: collaboration, peace and justice, self-expression, academic excellence and learning, love and belonging, holism, respect, caring for our environment, honoring diversity, community building, leadership, and creativity. The INPS pedagogy is organized around five core principles :

- Heterogeneous, collaborative classrooms

- Project based, experiential learning

- Integrating language and content integration

- Leveraging native language

- Local autonomy and responsibility

With 450 students and 28 teachers, the school is structured so that a team of five to six teachers work with a group of 75-100 students with ninth and tenth graders heterogeneously mixed. The small size of the school means that the school can practice democratic decision-making with most decisions made by the teachers, including the decision they made several years ago to move to mastery-based learning.

Learning Outcomes

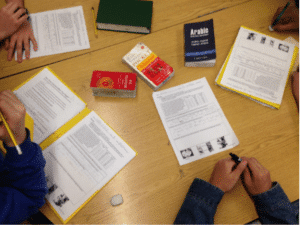

Flushing International organizes its teaching cycle around three types of learning outcomes: work habits, language, and academic disciplines. Teachers meet once a week within their academic disciplines and their cohort teams. This has allowed the academic teams to do norming around the learning outcomes, and the cohort teams to create more interdisciplinary projects. Given that language development is so important within the school, there are cross-cutting language outcomes:

L1. Student reads and/or writes in English for information and understanding .

L2. Student listens and speaks in English for information and understanding.

L3. Student reads and/or writes in English for critical analysis and evaluation.

L4. Student listens and speaks in English for critical analysis and evaluation.

L5. Student reads, writes, speaks and/or listens in English for classroom and social interaction and response.

Rubrics are organized around four levels: needs improvement, competent, good, and outstanding. Rubrics are used extensively at Flushing International – for specific outcomes (e.g., math outcomes), for products such as research papers, and for graduation portfolios (see science graduation portfolio). (Here is an example from mathematics.)

Even physical education has learning outcomes. Notice that they are broader than learn to play volleyball or participate in activities. This is important, as several educators have told me that the New York graduation requirements for gym have been the downfall of many students on their way to graduation. By having broader physical education outcomes, there are multiple ways for students to demonstrate mastery:

Content Outcomes for Physical Education

Demonstrates knowledge and skills to create and maintain physical fitness.

Develop the knowledge and ability necessary to create and maintain a safe and healthy environment.

Understand and be able to manage personal and community resources to engage in physical activity.

Learning Outcomes and Essential Questions

Many schools I’ve visited emphasize the transparency of mastery-based learning by putting the outcomes or standards up in the classroom. Transparency can be helpful in motivating students, but it isn’t the same as engaging them. At Flushing, there is a combination of essential questions that get the students thinking about clear outcomes.

- In a classroom made up of ninth and tenth graders, we watched students discuss the essential question, “How can folktales enrich and transform our lives?” They had seen The Lion King and their task was to write and perform a puppet show of their own exploring the essential question.

- In a science classroom, essential questions for evolution included, Why does an organism evolve?For biometrics, it was, How does an understanding of body systems increase one’s ability to make informed decisions on health issues? The learning outcomes included: I can explain evolution and the mechanisms of evolution; I can draw conclusions; I can read and write in English for critical analysis and evaluation; and I can collaborate with others.

Using Grading As Part of the Learning Process

Flushing International has created a reflective process for students to use after the release of progress reports (otherwise known as report cards). This helps students to better understand the grading system, celebrate their achievements, and address the areas they need to strengthen.

In a conversation with students, we asked, “How do you feel the scores in JumpRope reflect on what you know and can do? Is it capturing who you are as a learner and where you are in your learning process? In what way is it not accurate?”

Student responses included:

- The grading helps you realize when you don’t know something and need do something about it.

- Sometimes teachers give me more time at end of class to go back and demonstrate my learning at a higher level.

- I can tell when something is missing and I can talk to my teacher about ways that I can demonstrate that I have learned it.

- It accurately reflects that I struggle in chemistry sometimes.

- How do you know if I am prepared for college? I can look at JumpRope and know exactly what I need to learn and know. It tells me what to work on and where I need to ask for help.

- It gives you hope. I always have the opportunity to improve my grades.

Parents receive training in JumpRope, as well. Given that many parents have no English or limited English, the color-coding JumpRope uses for levels of mastery is especially useful. Green for “good” and “outstanding,” yellow for “approaching competence,” and red for “needs improvement.”

How Is Mastery-Based Learning Helping Students and Teachers Improve?

“A teacher will never say no to you when you ask for help.” That principle, emphatically stated by a student, captures one of the core values of competency-based education. Students can ask for help during Team Intervention periods twice a week as well as after school.

The topic of how to help those students who are really struggling ran through the conversations. Milczewski explained, “I am much more focused and goal-oriented when I’m conferring with students. In my advisory, mastery-based grading has changed how I talk to them about how they are doing in other classes. We always look at their work habits. That is going to tell you everything.” For students who are really struggling, Jordan Wolf suggested that the key is seeking ways to build success, “Sometimes it is important to find small chunks that give a roadmap to success for students. In JumpRope, I can expand down to a much more granular level until I can find a place to focus in which the student can build success on one or two things. After they realize they can be successful, they’ll be willing to try a little more.”

To make sure students get extra attention when they are having difficulties, a policy has been developed where a 1.7 triggers an intervention. There is also a policy for course extensions when students have not been able to reach all the learning outcomes. The expectation is that students will finish everything by the end of the following semester.

Summer school has changed, as well. Hesseltine explained, “Summer school is very targeted and highly personalized. Each student, focuses intently on outcomes he or she needs to master.“

Mastery-based learning is also helping teachers improve their own learning. Milczewski explained, “When I look at JumpRope and I see that a majority of students are having difficulty with a specific outcome, it tells me two things. One, I need to re-teach it, and two, I need to reflect on my own teaching to find a better way to reteach it.”

The Power of Performance-Based Assessments

Flushing International has been investing in building up performance-based assessment tests (PBAT).

The Flushing International team see PBATs as a much better strategy than exams because students are required to make presentations and communicate their findings. The mastery-based structure has worked well with PBATs, as teachers have had to calibrate what competent, good and outstanding look like for the 9th-10th grade band as compared to the 11th-12th grade band. Flushing International’s language learning outcomes are assessed in all of the PBATs, as well.

Flushing International is part of an English Language Learners Regents waiver granted to the Internationals Network for Public Schools, which is similar to the Regents waiver granted to the New York Performance Standards Consortium. Consortium and International schools are empowered to use PBATs instead of Regents exams as culminating assessments in specific courses. At the International schools with the ELL waiver, students are required to take the English and Math Regents exams. In addition, at a minimum they need to pass PBATs in History, English, Science, Math and Native Language as well as other areas that can be decided at the school-level.

The schedule has also been designed so that teachers are able to help students prepare for the PBAT oral presentations. Each teacher mentors five students through the process. Students understand the value of PBATs. One student explained how important revision is in the process of the PBATs, “We plan out what we are going to do and then have at least two revisions. Our mentors give us feedback and then we do even more revisions. Every time you think you are done, we find that we need to continue working on it.” This focus on revision is one of the ways that Flushing International is able to perform their magic of helping students with little or no English skills learn to prepare college-level essays within four years.

Students value the PBATs. One student explained, “PBAT is way better than Regents. The PBAT shows that you understand because you have to explain it to five teachers. It better prepares you for college.” Another student added, “In the real world, we need to communicate with others. It’s preparing us for the real world, not just about taking a test.”

A Final Thought

At first glance, it is easy to categorize Flushing International as a specialized model that only works for new immigrants. However, that would be short-sighted. The International Schools model will work for all students. Certainly there are plenty of low-income students who do not have strong English language skills, and too many students are thrown into remediation courses when they arrive at college. Furthermore, communities across the country are finding themselves serving new immigrants. Although national policy may change the flow of refugees from poverty, war and drought probably won’t.

If we want to design from the edges to make sure that students with the largest educational challenges are well served, it is worth taking the time to visit a competency-based International School to see how you might strengthen language and literacy throughout your school.

See also: