Michael Barbour: Distance Education, New Zealand

Education Domain Blog

First of all I would like to congratulate the International Association for K-12 Online Learning (iNACOL) on the creation of this research into practice blog. It is a positive resource that is long overdue. I would also like to thank Kathryn Kennedy for allowing me to post the first entry to this new blog. As a long-time K-12 online learning blogger (see Virtual School Meanderings), I am honored to be given this task.

Like many jurisdictions, distance education at the K-12 or primary and secondary level has a long history in New Zealand. The introduction of distance education to the schools sector (i.e., K-12 environment) began around 1922 with the introduction of The Correspondence School (Rumble, 1989). By the 1990s many rural area schools were facing challenges with providing a wide range of curricular opportunities, particularly in the senior secondary levels. These challenges led seven area schools in the Canterbury region to create the Canterbury Area School’s Association Technology project (CASAtech) (Wenmoth, 1996). The Kaupapa Ara Whakawhiti Mätauranga (KAWM) project began in 2000 and was the first e-learning cluster to develop (Roberts, 2009). Over the next decade, these early initiatives would serve as the model for approximate 20 e-learning clusters that would eventually become the Virtual Learning Network (VLN) – a loose coalition of individual providers of online distance education. At present, there are five main types of providers currently responsible for the delivery of distance education, including online and blended learning, in the schools sector in New Zealand: Te Aho o Te Kura Pounamu/The Correspondence School; approximately 20 VLN e-learning clusters; three regional health schools; 13 urban-based, regional fiber-based loops; and some tertiary institutions.

The past two years there have seen significant changes in the provision of virtual learning in the schools sector in New Zealand. During 2010 the Ministry of Education (MOE), along with CORE Education, revised and updated the Learning Communities Online Handbook – a document designed to provide e-learning clusters with guidance as they moved on their journey from a conceptual idea to a mature and sustainable cluster (Ministry of Education, 2011a). The MOE also announced its plans for the Ultrafast Broadband in Schools (UFBiS) initiative will ensure Internet access to 95% of the nation’s schools by 2016 (Ministry of Education, 2012). In 2011, the Distance Education Association of New Zealand (DEANZ) commissioned a study into the development of virtual learning in New Zealand (Barbour, 2011), while the Virtual Learning Network-Community (VLN-C) commissioned CORE Education provide future direction to this national virtual learning organization (Wenmoth, 2011). Later in the year, the MOE announced that it would create a Network for Learning to provide significant tools and resources for schools (Ministry of Education, 2011b). Finally, this past year a Parliamentary Inquiry into twenty-first century learning environments and digital literacy was conducted (New Zealand Parliament, 2012).

The purpose of the forthcoming CORE Education white paper is to examine the current state of virtual learning in the schools sector, as well as chart a vision for the virtual learning in 2016 and beyond (i.e., following the completion of the UFBiS initiative).

Primary and Secondary e-Learning: Examining the Process of Achieving Maturity

During the 2011 school year, as a study commission by the DEANZ, I examined the development of the VLN e-learning clusters and the barriers these clusters faced in achieving sustainability and maturity (Barbour, 2011). I recommended a significant re-organization to the way primary and secondary online learning was structured and supported. The organizational model recommended was focused upon expanding the brokerage role of the MOE, providing more regional support to allow for greater regional cooperation, and continuing to provide individual e-learning clusters the flexibility to address local needs.

Expanding the Brokerage Role of the Ministry of Education

At present, the MOE provides a brokerage of services that are focused on tools. The MOE currently supports a videoconferencing bridge that allows many of the VLN clusters to conduct their synchronous instruction. The MOE also provides support for the learning management system (LMS) Moodle, along with a variety of other tools that could be used for asynchronous online instruction. Finally, the MOE provides a registration system that allows schools to enroll their students into distance courses – both from the cluster that they may be a member of and also from other clusters that may have excess capacity (see http://pol.vln.school.nz/). The individual VLN clusters are responsible for course development and, in many instances, the teachers from those individual clusters had independently created multiple versions of the same course. This has resulted in two, three, four, five and, even, six different versions of a course being developed; which is a considerable waste of resources. It was recommended that the MOE‘s brokerage services be expanded to include the consolidation and further development of an online course content repository.

Providing More Regional Support to Allow for Greater Regional Cooperation

From 2007 to 2009 the MOE provided funding for 18 administrative positions for the leadership of the various VLN e-learning clusters. Barbour noted that each of the individual ePrincipals, along with the principals and deputy principals from schools participating in various e-learning clusters, all spoke of the need for one or more funded leadership positions with the e-learning cluster. However, the full-time equivalent enrolment for the individual e-learning clusters ranged from a low of 8-10 students to a high of 300-400 students. Yet there was value in having regional leadership that had a closer proximity to the individual e-learning clusters and was able to understand the local needs of each cluster. As such, it was recommended that the MOE fund five to eight part-time or full-time regional coordinators responsible for specific geographic regions.

Continuing to Provide Individual e-Learning Clusters Flexibility to Address Local Needs

Historically, each of the VLN e-learning clusters was initiated to address one or more specific local needs. In some instances, this was due to the criteria of a particular request for proposals from some national funding scheme. However, in many instances the needs being addressed were genuine needs that the geographic collection of schools felt existed. The growth of the VLN from two or three isolated clusters to approximately 15-20 individual e-learning clusters is an illustration of the importance of addressing local needs through the initial developmental stage. It was important that this local connection was not lost. While there was a call for a greater level of services to be provided at the national level, as well as the creation of regional coordinators and a call for increased rationalization of the existing e-learning clusters, it was recognized that the needs of local schools could not be met solely through a centralized, national structure. There was a need for local e-learning clusters that were organized around geographic or like-minded visions (e.g., boys schools, character schools, Mãori schools, etc.).

Business Case: Virtual Learning Network Community (VLN-C)

In 2011 the VLN-C commissioned Derek Wenmoth of CORE Education to prepare a business case that examined the future organizational and legal structure of a sustainable VLN-C. The timing of this request came shortly ahead of a review of the current funding support for the VLN, and the MOE were looking to the VLN-C to provide a substantive case for why funding should continue. Three options were presented as a basis for moving forward (Wenmoth, 2011).

Option One: Establish the VLN as a business unit within the Ministry of Education

This would involve the MOE taking responsibility for treating the operation of the VLN as a part of its own internal operations in providing services for schools. Funding would be provided through an annual appropriation that supported all areas of activity of the VLN. The VLN-C council would exist as an expert reference group to the MOE, and as a professional coordination and advocacy group within the VLN-C. This option would guarantee ongoing funding for the VLN and allow the VLN-C to remain influential at a national level, while focusing attention on operational issues and support. However, the overall locus of control would shift to the MOE.

Option Two: Establish the VLN-C Trust as an independent company.

This option would enable the collection of clusters nationally to operate in a federated sense – consistent with the notion of a “fractal” organization, or “network of networks.” This would require the VLN-C to establish a fully self-funded model, with funding coming through a variety of channels, including individual membership fees, cluster membership fees and fees for service through the brokerage model. The national organization would act as a broker on behalf of the member organizations, leveraging the scale of membership to negotiate deals on services for members. The company would coordinate the provision of advice for members, negotiating and providing professional development and other consulting services. A formally established governance model would be required, with a board and operations staff employed by the company. This option enables the VLN-C to operate independently from the MOE, in a sustainable business model.

Option Three: Establish the VLN Trust as a professional organization

The primary focus in this option is on representation and advocacy, along the lines of other professional organizations. This is essentially a representational model, focused on advocacy and influence. The interests of the constituent members are “held in trust” by the elected members of the professional organization. Funding for this model would come from the payment of a membership fee. As a professional organization funded by members the VLN-C would be able to provide an “independent voice” on matters relating to the operation of the clusters, and be strongly represented in all policy and strategy development.

Consolidating a Way Forward for New Zealand Schools

While the DEANZ report to the MOE (i.e., Barbour [2011]) and the business case for the VLN-C (i.e., Wenmoth [2011]) were tasked with separate goals, there is a great deal of overlap in the model proposed by Barbour and the first two options proposed by Wenmoth. However, one of the main limitations of both of these reports was the strict focus on the VLN e-learning clusters and the VLN-C. This VLN focus meant that the broader range of providers of primary and secondary a distance education were not considered in either of the proposed models. For example, the role and funding provided to The Correspondence School and the SuperLoops – along with the operation of the three health schools and the growing number of tertiary providers – are all a part of the context of virtual learning in New Zealand’s schools sector and should be considered within the context of a new organizational model.

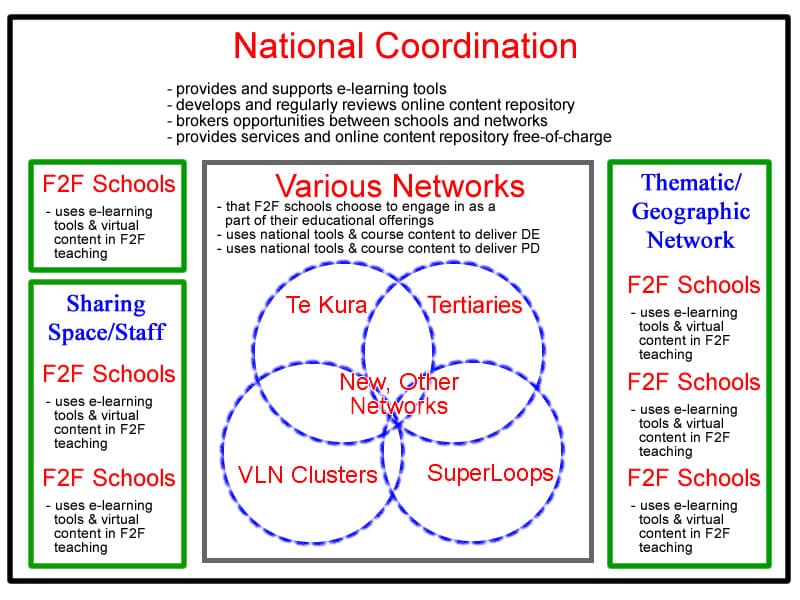

Given this multitude of differing players in the virtual learning environment in New Zealand, there is one potential organizational structure that could be accommodated within the existing and impending realities that allows schools to become more networked in their own orientation towards student learning.

Figure 1. Potential organizational structure for the delivery of virtual learning in New Zealand

Under this organizational structure, one or more (ideally one) national body would have three main responsibilities:

- provide and support asynchronous and synchronous tools for virtual learning (e.g., video-conferencing, virtual classrooms, LMS, student information systems, e-portfolio programs, etc.),

- develop and maintain a repository of online course content that is available to users free-of-charge, and

- provide brokerage services for users that wish to provide excess capacity to or collaborate with others.

This structure would allow existing distance education providers to focus specifically upon the provision of distance education and professional development (potentially even to specialize with certain geographic, pedagogical, ethnic, gender, etc. foci). It would also allow individual schools and teachers to use virtual learning tools and virtual learning content with their face-to-face students in a blended format or a “flipped classroom” model. Finally, it would allow individual or multiple schools to consider creative scheduling and delivery options (e.g., a course in a school where the teacher is scheduled in one slot and the students are scheduled throughout the day or where two teachers at two different schools collaborate to combine their students into a single class – see the “Opening Classrooms” section of Barbour [2011]).

Practical Implications

While the history, context, and recommendations this particular white paper are quite specific to New Zealand, there are some more generalized practical implications to a broader audience. Within the North American environment, we have seen number legislative and regulatory changes to encourage – as well as a general push for the greater incorporation of – online and blended learning in K-12 education. As Watson, Murin, Vashaw, Gemin, and Rapp (2012) have reported, district-based programs – particularly blended learning initiatives – appear to be the fastest growing form of K-12 online and blended learning. Further, Stalker and Horn (2012) have described several different models that these blended learning opportunities can be provided (beyond the traditional supplemental or full-time online learning).

The provision of access to the technology (e.g., LMS, student information system, synchronous tools, etc.), as well as technical support, from a centralized source removes one of the main barriers that prevent schools and school districts from implement online and/or blended learning. Another barrier to the implementation of these online and blended learning models is access to high quality virtual learning content. In most instances, school and school districts have to invest money to create their own content or pay annual fees to lease propriety content. The creation of a centralized online course repository that schools and school districts could access free-of-charge would remove a second major barrier.

There are some North American jurisdictions that can provide a model that could be implemented through Canada and the United States (and internationally). Canadian provinces of Ontario, New Brunswick, and Newfoundland and Labrador all provide a centralized learning management system and online course repository that all of the virtual learning programs and brick-and-mortar schools in the respective province can use free-of-charge. In the United States, iNACOL recently released a report entitled Open Educational Resources and Collaborative Content Development: A Practical Guide for State and School Leaders, which provided educational leaders with a guide describing the benefits of OER, a framework for planning, and strategies for successful collaborative content development. This was followed by a second report entitled OER State Policy in K-12 Education: Benefits, Strategies, and Recommendations for Open Access, Open Sharing, which provided a rationale for policymakers on why open education resources were important and recommendations on how to implement strategies to ensure greater sharing of learning materials. iNACOL has also been significant supporters of initiatives like the National Repository of Online Courses (NROC) and the open courseware initiative undertaken by the Open High School of Utah (now Mountain Highs Academy) – both of which have been featured in numerous webinars and presentations at the annual Virtual School Symposium (now iNACOL Symposium). The CORE Education white paper, which is available at http://www.core-ed.org/thought-leadership/research/virtual-learning-impetus-educational-change-charting-way-forward, provides a useful organizational framework and policy model that could be implemented at the state/province or regional level to encourage the growth of K-12 online and blended learning.

References

Barbour, M. K. (2011). Primary and secondary e-learning: Examining the process of achieving maturity. Christchurch, New Zealand: Distance Education Association of New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.vln.school.nz/mod/file/download.php?file_guid=114023

Bliss, T. J., Tonks, D., & Patrick, S. (2013). Open educational resources and collaborative content development: A practical guide for state and school leaders. Vienna, VA: International Association for K-12 Online Learning. Retrieved from https://www.inacol.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/inacol_OER_Collaborative_Guide_v5_web.pdf

Ministry of Education. (2011a). Learning communities online handbook. Wellington, New Zealand: Author. Retrieved from http://www.vln.school.nz/pg/groups/2644/lco-handbook/

Ministry of Education. (2011b). Innovative learning network to lift student achievement. Wellington, New Zealand: Author. Retrieved from http://beehive.govt.nz/release/innovative-learning-network-lift-student-achievement

Ministry of Education. (2012). Ultra-fast broadband in schools. Wellington, New Zealand: Author. Retrieved from http://www.minedu.govt.nz/theMinistry/EducationInitiatives/UFBInSchools.aspx

New Zealand Parliament. (2012). Inquiry into 21st century learning environments and digital literacy. Wellington, New Zealand: Author. Retrieved from http://www.parliament.nz/en-NZ/PB/SC/MakeSub/f/9/7/50SCES_SCF_00DBSCH_INQ_11275_1-Inquiry-into-21st-century-learning.htm

Roberts, R. (2009). Video conferencing in distance learning: A New Zealand schools’ perspective. Journal of Distance Learning, 13(1), 91-107. Retrieved from http://journals.akoaotearoa.ac.nz/index.php/JOFDL/article/viewFile/40/38

Rumble, G. (1989). The role of distance education in national and international development: An overview. Distance Education, 10(1), 83-107.

Stalker, H., & Horn, M. B. (2012). Classifying K-12 blended learning. San Mateo, CA: Innosight Institute. Retrieved from http://www.christenseninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Classifying-K-12-blended-learning.pdf

Watson, J., Murin, A., Vashaw, L., Gemin, B., Rapp, C. (2012). Keeping pace with K-12 online and blended learning: An annual review of policy and practice. Evergreen, CO: Evergreen Education Group. Retrieved from http://kpk12.com/cms/wp-content/uploads/KeepingPace2012.pdf

Wenmoth, D. (1996). Learning in the distributed classroom. SET Research Information for Teachers, 2(4). 1–4.

Wenmoth, D. (2011). Business case: Virtual Learning Network-Community (VLN-C). Christchurch, New Zealand: CORE Education.

Michael K. Barbour is the Director of Doctoral Studies for the Isabelle Farrington College of Education and an Assistant Professor of Educational Leadership at Sacred Heart University. He has been involved with K-12 online learning for over a decade as a researcher, evaluator, teacher, course designer, and administrator. His research has focused on the effective design, delivery, and support of K-12 online learning, particularly for students located in rural jurisdictions. Recently, Dr. Barbour’s focus has shifted to policy related to effective online learning environments, which has resulted in his testifying before House and Senate committees in several states, as well as consulting for Ministries of Education across Canada and in New Zealand.

– See more at: http://researchinreview.inacol.org/page/16/#sthash.eOy86BPG.dpuf