10 Principles of Proficiency-Based Learning

CompetencyWorks Blog

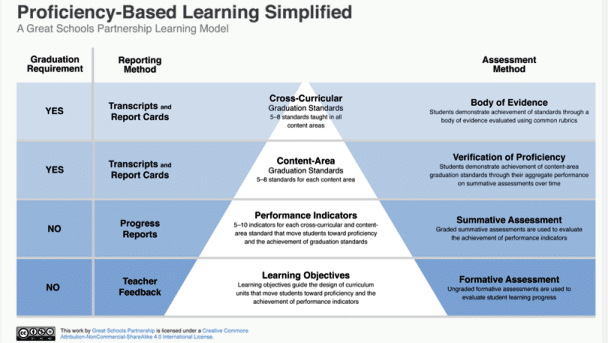

Great Schools Partnership continues to produce great resources to support states and districts converting to competency education. They have drawn from what districts are doing in New England and have created Proficiency-based Learning Simplified resources. They are a good resource for states, districts and schools to start the conversation about the new policies and practices that need to be put in place. We know that we are on a journey, and its a creative one, so don’t be surprised if you find that you want to take these ideas further or that you come up with other ways to address the policy and practice elements. No matter what, these resources will save you time in getting started and structuring the conversations needed to build clarity and consensus.

Great Schools Partnership continues to produce great resources to support states and districts converting to competency education. They have drawn from what districts are doing in New England and have created Proficiency-based Learning Simplified resources. They are a good resource for states, districts and schools to start the conversation about the new policies and practices that need to be put in place. We know that we are on a journey, and its a creative one, so don’t be surprised if you find that you want to take these ideas further or that you come up with other ways to address the policy and practice elements. No matter what, these resources will save you time in getting started and structuring the conversations needed to build clarity and consensus.

Here’s GSP’s 10 principles of proficiency-based learning:

In practice, proficiency-based learning can take a wide variety of forms from state to state or school to school—there is no universal approach. To help schools establish a philosophical and pedagogical foundation for their work, the Great Schools Partnership created the following “Ten Principles of Proficiency-Based Learning,” which describe the common features found in the most effective proficiency-based systems:

- All learning expectations are clearly and consistently communicated to students and families, including long-term expectations (such as graduation requirements and graduation standards), short-term expectations (such as the learning objectives for a specific lesson), and general expectations (such as the performance levels used in the school’s grading and reporting system).

- Student achievement is evaluated against common learning standards and performance expectations that are consistently applied to all students, regardless of whether they are enrolled in traditional courses, pursuing alternative learning pathways or receiving academic support.

- All forms of assessment are standards-based and criterion-referenced, and success is defined by the achievement of expected standards, not relative measures of performance or student-to-student comparisons.

- Formative assessments evaluate learning progress during the instructional process and are not graded; formative-assessment information is used to inform instructional adjustments, practices, and support.

- Summative assessments evaluate learning achievement and are graded; summative-assessment scores record a student’s level of proficiency at a specific point in time.

- Grades are used to communicate learning progress and achievement to students and families; grades are not used as forms of punishment or control.

- Academic progress and achievement is monitored and reported separately from work habits, character traits, and behaviors such as attendance and class participation.

- Students are given multiple opportunities to retake assessments or improve their work when they fail to meet expected standards.

- Students can demonstrate learning progress and achievement in multiple ways through differentiated assessments, personalized-learning options, or alternative learning pathways.

- Students are given opportunities to make important decisions about their learning, which includes contributing to the design of learning experiences and personalized learning pathways.