ACTIONS – Ideas and Strategies for School Leaders

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the fifth post in a 10-part series that aim s to make concepts, themes, and strategies described in Moving Toward Mastery: Growing, Developing and Sustaining Educators for Competency-Based Education accessible and transferable. Links to the other articles in the series are at the end of this post.

s to make concepts, themes, and strategies described in Moving Toward Mastery: Growing, Developing and Sustaining Educators for Competency-Based Education accessible and transferable. Links to the other articles in the series are at the end of this post.

School leaders are closest to teachers, who in turn are closest to students. As a school leader, your daily actions, the values you model, and the decisions you make about resources like time and people have a direct impact on teachers and on the quality of education. Toward the end of Moving Toward Mastery I describe the leverage that school leaders have in their roles (page 69). But, I stop short of describing specific actions leaders can take. This post picks up where the paper left off, offering three big ideas and ten action ideas for school leaders who are trying to grow, develop and sustain educators for competency-based education.

School leaders, my goal is not to tell you what to do — developing a change strategy is a very specific, local process. And, my goal is not to give you a lecture on what “should” be happening in your school. I recognize the complexity of the roles you play day to day. My goal is simply to offer ideas for actions that can serve as conversation points, entry points, or points of continuous improvement.

Three Big Ideas

Let me start with three big ideas about school leadership. These can be helpful as you reflect on your school and your role, as you engage your team in conversation, or as you prioritize starting points from the change strategies below.

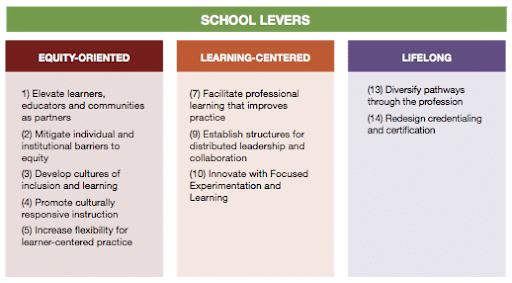

Schools are where equity is enacted. While district and state policy define systems, structures, and resources that enable equity, schools are where the real work is. As a school leader, you have significant leverage and power to cultivate equitable learning environments, experiences, and outcomes. There are several key aspects to this, including prioritizing diversity and representation in hiring, fostering equitable and inclusive conditions for your teachers, providing supports and enforcing accountability for teachers to become more equity-oriented practitioners, and allocating time for teachers to form relationships with students and families and work with one another.

Your leadership can model critical mindsets. Your leadership matters, and this starts with mindsets. In an earlier post co-authored with Transcend Education, Stacey Wang, Jane Bryson and I talk about the importance of teacher mindsets. What Transcend’s work also says, though, is that leader mindsets are critically important to shaping teachers’ mindsets. These include mindsets about adult learners and learning (e.g., “If adults get supportive feedback and coaching, they will grow in their productive mindsets and skills”) and mindsets about myself and my role (e.g., “I commit to having the appropriate levels of vulnerability and humility, while also recognizing that this is not at odds with having strength and clarity”). These mindsets get demonstrated in your daily actions and interactions, and in the decisions you make about resources like people, time, money, and space. Your teachers will grow (and so will your students) when your daily actions and decisions create the conditions for them to do so.

Time is a vital lever. As a school leader, you do not always have full control of every variable in your school, but you almost always have leeway in how you use time. Why does this matter? Too often, we expect that teacher learning and development — particularly around equity — is additional work. Talking to parents? That happens at night or early in the morning. Meeting one on one with students to understand what’s happening in their families? That’s over lunch. Collaborating with teachers, or taking the time to reflect about race and power in your classroom? That’s on your own time, or never. The truth is, the way we use time says a lot about what matters to us. As a school leader, you can create the conditions for the type of teaching you want to see and send a very clear message about values by allocating time for the following: regular and purposeful teacher collaboration, including co-planning, improvement activities, and calibration; time for teachers to observe each other’s practice, provide feedback, and engage in a purposeful community of practice; time for teachers to form strong relationships with students, families, and communities. Often, making time flexible is a key part of this effort. This might sound terrifying. For a lot of school leaders, nailing down a master schedule is a nightmare. But even within that master schedule you can create pockets of flexibility that allow you to be responsive to teacher needs, and allow teachers to be responsive to student needs. Flex blocks, personalized learning time, and other mechanisms can help you use time as a responsive resource.

Ten School Leader Actions

Get Started

- Engage your staff, students, and families. Your community has perspectives that you may not know about on the state of teaching and learning in your school. Engage their voices early on to support assessment and planning, and to enlist their partnership and leadership down the line.

- Assess where you are. Based on your community input, assess the current state of teaching and leading in your school. Where are you relative to the picture presented in Moving Toward Mastery? Where do you want to be? What problems are you solving for?

- Assess your own leadership. Community input, coupled with your own self-reflection and input from your supervisors and mentors, will help you get clearer on the state of your own leadership. What are you currently doing that will help you lead for the vision you hold? What strengths can you build on? What are you doing that will impede progress? Where do you need to grow? It’s not just knowing these strengths and growth areas that matters, it’s sharing them with your community. Doing so will model transparency and vulnerability and allow your community to hold you accountable.

Develop Key Learning Structures

4. Articulate an instructional vision and teacher competencies. The Learning Accelerator offers a starting point for this work. Ask yourself, “What do my teachers need to be successful within our model? And, what does mastery of each competency look like in action?” To these key questions I would add two more. First, “What instructional or pedagogical principles are most important in our school?” Second, “is there symmetry between teacher competencies and student competencies?” Make sure you engage teachers – and perhaps even students – in answering these questions.

5. Integrate choice for teachers. Traditional professional learning sits everyone in the same room to learn the same thing at the same time when the schedule says it’s time for PD. Get outside this box. Allow your teachers to identify their growth areas within your pedagogical framework and teacher competency model, and give them some voice in deciding how they want to learn.

6. Identify how teachers will demonstrate growth and mastery. Traditional professional learning is time-based: teachers get the credit for learning if they show up. But this (1) does not take into account what they already know and can do, and (2) does not allow them to demonstrate or measure their progress. Consider ways to integrate feedback and demonstrations of learning into teachers’ professional development. Microcredentials can be a great way to do this.

Foster Collaboration and Leadership

7. Prioritize time for teacher collaboration, including peer observation and feedback. Often when I ask school leaders if they make time for teacher collaboration, they talk about monthly staff meetings or trainings in the summer. Schools that truly prioritize teacher learning and development make collaboration a core aspect of regular practice. Teachers plan together, look at student work together, engage in improvement activities together, calibrate their assessments together, and observe each others’ practice. Make time for these activities in your schedule, and make sure the collaboration is meaningful. Clarify the purpose and use protocols to guide the practice.

8. Create structures to distribute leadership. Distributed leadership is key: it creates a culture of ownership, fosters collaboration, gives teachers opportunities to grow (which makes them want to stay!), and makes change processes more manageable. So, distribute leadership to teacher leaders, partners, parents, and others in your school. It will be helpful to read up on distributed leadership, as well, to understand what makes it successful and how your own leadership might adjust accordingly.

Create Conditions for Equity

9. Prioritize diversity and representation in your staff and foster inclusion for adults. If you have some discretion in hiring, prioritize diversity, representation, and cultural competency when hiring, and make concerted efforts to foster inclusion amongst your staff. Staff who do not feel safe, respected, or included in a multicultural community will have a more difficult time fostering that experience for students.

10. Allocate time and supports for teachers to address personal bias and hold them accountable for doing so. Almost all teachers will need to address their mental models and personal biases when making the shift toward student-centered and equity-oriented teaching. This does not happen by accident, and it does not happen overnight. One of the most important things you can do as a leader is to name and support these shifts: normalize them, explain why they matter, articulate their urgency, and tell teachers what you will do to help them. Then, make sure you hold teachers—and yourself!—accountable for doing the work.

Read the entire series:

- Introducing Moving Toward Mastery

- Entry Points: Moving Toward Equity-Oriented Practice

- Voices: Developing Teacher Mindsets

- Entry Points: Moving Toward Learner-Centered Practice

About the Author

|

Katherine Casey

Katherine Casey