Breaking out of the Boxes at Building 21

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the first post about my site visit to Building 21 in Philadelphia. Read the second here.

This is the first post about my site visit to Building 21 in Philadelphia. Read the second here.

Of all the schools and districts I’ve visited over the past four months, it has taken me the longest to write about my visit to Philadelphia’s Building 21 (there is also one in Allentown) because their ideas just blow me away. I’ve had to take time to absorb them and figure out how to describe them to you. I’m guessing I still don’t fully understand the rationale and implications of some of their design decisions. The team at B21, led by co-founders Laura Shubilla and Chip Linehan, have been so intentional, so thoughtful, so focused on drawing on what we know is best for helping adolescents learn, and so out of the box. As districts both big and small make the transition to competency-based education, Building 21 is one to watch as it cuts the path toward new ways of structuring how we organize learning and advance students.

A few of the big takeaways from my visit to Building 21 are:

- Designing for students with a broad spectrum of skills and life experiences

- Cohesive competency-based structure with a continuum of performance levels

- Two-tiered system to monitor student progress

- Information system that is designed to be student-centered and teacher-enabling (see tomorrow’s post)

This post will hopefully be helpful in explaining B21. However, if you are interested, I highly recommend taking thirty minutes to look through the Competency Toolkit and the Competency Handbook. They’ve done a fantastic job at making their model accessible for students, parents, teachers, and all of us who want to learn from them.

Building 21 Competency-Based Structure

B21’s design team – co-founders Laura Shubilla and Chip Linehan, Thomas Gaffey, Sydney Schaef, Sandra Moumoutjis, Angela Stewart, and founding principal Tara Ranzy – are upfront that, as they enter their second year of operation, the design remains ahead of implementation. They are also grateful for the opportunity to visit other schools, including Boston Day and Evening Academy, Summit, and schools that have worked with Reinventing Schools Coalition for inspiration, great practices, and insights into competency education.

Design Starts with Knowing Your Customers

One of the big starting points for any design process is to know your customers – in this case, the students. Designing schools that are truly student-centered isn’t as easy as one might think. In many of the most developed competency-based districts, schools are still structuring learning around grade levels and courses, not students. I can’t tell you how often I hear new school designers comment that their model didn’t work as planned, as they were overwhelmed by the fact that so many students enter high school with elementary or low middle school skills. They are either honest that they didn’t take that into consideration in their design or, disappointingly, seek to restrict who is able to enroll in their school (this is a huge red flag that they are constraining innovation and trying to control inputs).

The team at Building 21 brought deep knowledge about the young people in Philadelphia. I first met Shubilla in her role as co-director of the Philadelphia Youth Network. Gaffey and Sandra Moumoutjis both started as teachers in Philadelphia. They are designing for students to enter ninth grade with a Grand-Canyon-like spectrum of skills – they are designing for the student who didn’t receive an adequate education in elementary or middle school; who was repeatedly suspended; whose family moved a lot in search of better housing, better jobs, safer neighborhoods, and better schools; and who has incredible aptitude that may skyrocket forward in a few domains, but who may not want to work on the stuff considered uninteresting. They are designing for students who have suffered upheaval and violence in their lives. They are designing to meet kids where they are.

Values

You know right away that the design at B21 is going to be different just by glancing at the values that drive the school: power, responsibility, mindfulness, courage, interconnectedness, and transparency. The descriptions of each are powerful in and of themselves, tossing me into a moment of reflection about what it means for any individual, let alone an entire school, to embrace these values. Take interconnectedness: Learning involves the connection of ideas, information, people and experiences. We seek to find and build upon the points of connection in ourselves and in our community. We often talk about how important it is for teachers to form relationships with students or to have strong communities of peers for students. Yet bias, both implicit and intentional, still exists. The interconnectedness value takes us much farther as it encourages us to seek out connections. In an age where we find ourselves as a country having to openly face the different life experiences we have based on the color of our skin or our religion, this value can guide teachers, students, and parents to seek ways to understand different experiences, build strong relationships, and, most importantly, to listen to each other.

Interconnectedness also leads to cultural relevance and respect. B21 is dedicated to helping students create meaning and make connections. Teachers are encouraged to organize curriculum that speaks to student’s lives. For example, Amoreena Olaya, a social studies teacher, has organized an African-American history course that walks students through our nation’s history of enslaving Africans and the Civil Rights Movement, and leads up to the current movement to reduce police brutality. As the students practiced using Cornell Notes, the teacher used an asset-based analysis that emphasized how people who were enslaved grew different crops and highlighted their role in increasing the economic strength of the country. Across the wall, a banner carried a quote from Bob Marley, “Emancipate yourself from mental slavery. None but ourselves can free our mind.”

The Overall Pedagogy

Building 21 has designed an overall pedagogy based on what we know about adolescent development, learning sciences, motivation, engagement, and serving students who have experienced failure and trauma in their lives. The pedagogical strategy is based on a combination of the student as designer (think student agency and self-directed learning), problem-based learning, experiential learning, and personalized learning pathways. If it can be helpful, students have access to Compass Learning during a Flex period to provide additional support.

In addition to designing their entire model to meet students at their individual performance levels, B21 has invested in developing a strong focus on Habits of Success, including offering a course on mindfulness and hiring a social worker to help students build skills to navigate their lives.

Mindfulness: One of the things you notice at B21 is the difference between the ninth and tenth graders in terms of maturity. It’s even more remarkable because most of the tenth graders didn’t choose to come to B21; it was just one of the few remaining options available to them. B21 has a number of strategies to engage students in becoming more reflective and intentional about their behaviors. One is that there is a teacher dedicated to teaching practices to increase mindfulness to students.

Later in the week, I had the opportunity to attend the Youth Transition Funders Group meeting in Philadelphia and learned about the city-wide strategies to address the trauma that children endure growing up in communities with a high degree of violence. Developing mindfulness, or being able to know your own feelings and calm oneself when something triggers you, is a big step for any of us, but especially for students who have been witnesses or experienced violence.

College and Career Readiness Competencies

B21’s competency model is a “Learning What Matters” (LWM) competency model, jointly developed by the School District of Philadelphia. It was influenced by the simplicity of the Great Schools Partnerships model for graduation standards (although they point out that there are differences, such as keeping reading informational text and reading literature as separate skills to ensure equal emphasis). The competency model has eight domains: social studies, math, ELA, science, art and humanities, health/PE, world languages, and habits of success. All competencies were written in student-facing “I Can…” statements. These competencies make up the essential skills that students will need for graduating college/career ready. For example, English Language Arts has eight competencies and Habits of Success has five (growth mindset, decision-making, work and time management, self-regulation, and social skills and awareness). Within each competency, there are skills. Got it? Domain, competencies, skills. You can find all the competencies here.

Example

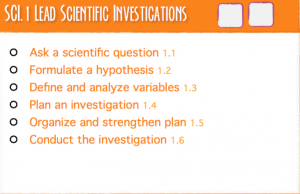

Domain: Science

Competency: Lead Scientific Investigations

Skills: (see below)

Continua of Performance Levels

Here is where it gets a bit different. B21 and the School District of Philadelphia designed it so each competency has a continuum of performance levels. I’m going to say it again – each competency is organized into performance levels. This is different from just having a lot of standards listed under a broader competency. B21 expects their teachers to be able to calibrate performance levels of students throughout the high school experience. The students’ focus is on building their skills of the overarching competencies, which always sound more meaningful than the list of skills or standards that make up each competency.

Example Continuum

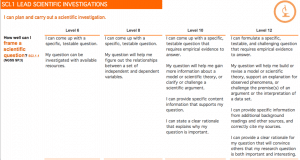

Competency: Lead Scientific investigations (SCI.1)

Skill: Frame a scientific Question (SCI.1.1)

The second design decision they made regarding the continuum is the structure. The levels form a continuum of six through twelve, with each student working in their individual zone. There aren’t indicators for meeting performance at every grade level, a structure that mirrors the standards from which their competencies are derived. For example, their ELA continua have levels 6, 7, 8, and 10 and 12 (based on the Common Core grade level bands at the high school level). Their science continua, as you see above, have levels 6, 8, 10, and 12, mirroring the grade level bands of Next Generation Science Standards for Science and Engineering Practices. For scoring purposes, they have designed it so that if you have demonstrated Level 8 but aren’t yet to Level 10, then you are at Level 9. It’s taken me a bit to get a grip on this idea. The B21 team explained that they wanted to avoid using rubrics that were either too vague or deficit-based. They wanted a structure that could inform instructional design, guide the provision of student feedback, and guide assessment design, all serving to provide a roadmap for students to move from one level to the next. Gaffey pointed out, “We would love to have every continua start with 1 where it makes sense. Even better, we dream about a time where performance level is separated completely from traditional grade levels. Imagine 1-8 or 1-10 where the levels are intentional and directly relate to the progression of the skill.” (B21 is continuing to refine their scoring guides. Here is an example for Making Presentations.)

Certainly one benefit of this model is fewer indicators to be assessing. It also helps to answer something I’ve really been struggling with – so much of high school is about strengthening skills and tapping into those skills, including analysis, synthesis, writing, technical skills, and background knowledge, to tackle problems with greater complexity. I still haven’t seen a model that is able to define by indicators the difference between tenth and eleventh grade writing, which is as difficult as defining the difference between eleventh grade analytical skills and those in twelfth grade. By reducing the number of indicators to be calibrated and assessed, B21 allows teachers to focus more deeply on working with students. We think about levels based on our understanding of age-based grade levels, but what if the levels were based on the domains, skills, and learning progressions instead?

Students have to move from where they start all the way to graduation levels. B21 is really upfront with their students: “If your performance level on the continuum matches your grade level (or higher!), then you are on track to college and career readiness.” The scoring guide for the performance levels are totally transparent, as you would expect in any competency-based school. More importantly, they encourage the students to become really familiar with the continuum as one of the ways to be successful in the school.

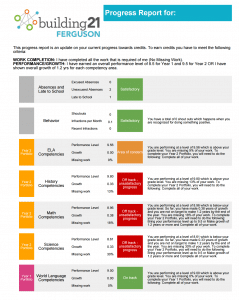

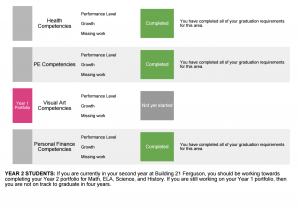

Students and parents have access to reports that are updated weekly (the progress reports are kept in Google Docs and data is exported by Slate weekly). Printed copies are sent to parents each marking period.

Tara Ranzy, founding principal of B21, reminded me, “Be sure to celebrate the competencies. When students progress to the next performance level, celebrate. Achievement always needs to be celebrated.”

Reflection: You can imagine that someday, districts might have a continuum of performance levels from K-12 or even first year in college. Given that higher education has yet to come to an agreement or be fully transparent about what freshmen level skills need to be, if we extend the B21 structure, I can imagine an introductory level 13 for most colleges and universities and an advanced level 13 for more elite colleges. Or perhaps we might see three or more tiers. The value is taking the mystery out of what it means to be college ready from the perspective of individual colleges and universities so we can create the transparency needed for a much more equitable education system.

Performance Levels through Assessments

Now it’s going to get even trickier – B21 doesn’t expect every skill or competency to have a different assessment. They design assessments in a way that allows students to demonstrate the level they are at. Thus, if they put in a lot of effort with plenty of practice and/or revisions, they may jump a level in writing in less than a year. If they turn in a shoddy draft without much effort, it might be leveled one or two levels below what they are capable of. This means students are going to be encouraged to do their very best.

B21 uses performance tasks to ensure that students are able to apply their skills. Students get credit for demonstrating grade level performance (with the exception of the credits based on growth for students with multi-year gaps as described below). B21 has three criteria for designing performance criteria:

- Rigorous: Performance tasks are challenging enough for students to demonstrate the competencies on grade level.

- Authentic: The tasks have meaning in the world beyond school, representing things that students will have to do in college, career, or life.

- Relevant: The tasks are making connection to the student’s life, interests, and goals.

Gaffey emphasized, “Relevance is a nuanced concept. Connecting to passions and interests is one way of creating relevance. The other is when students are motivated by or engaged with any problem, task, or activity, then it is relevant to them. We want to become great educators who are really good at engaging students with things like vocabulary and factoring polynomials.”

B21 directly links performance tasks to helping students prepare for college. In shaping their model, B21 looked at a study conducted by reDesign that had examined course syllabi from higher education institutions across the country to determine the types of tasks and typical workload for freshmen year. Here is what they found: approximately 90-100 papers, 6 presentations, 75 text-based discussions, 21 problem sets, 5,000 pages read, 12 argumentative essays, 8 examinations, and 6 lab reports. Students understand that each performance task is another step on the way to college. Example of performance tasks include essays, research projects, Socratic seminars, photography exhibits, design projects, annotated reading, science experiments, problem sets, film, engineering projects, and multimedia presentations.

The B21 team is continuing to think about how to build the capacity of students to produce at college level. How many arguments should a junior have to write compared to senior? Over time, they expect to refine the portfolio expectations they have developed so students can understand their own progress toward college readiness.

Scoring

B21 has three rules for scoring – I won’t go into detail because you can read about it in the Handbook on pages 7-12. First, they are explicit about how much evidence students need to show for each skill within a competency. Teachers then use three rules:

- Lowest Goes: If a student’s work is between two performance levels, they will get the lower one. Sounds terrible, but how else can you make sure kids are really proficient?

- Show Evidence: Students have to give evidence for the indicator (skill) at least at the lower level (level 6), or it shows up as insufficient evidence. Again, B21 is looking to make sure students are learning every skill within a competency.

- Level Up: To get that in-between level on the continuum, you need to meet all the expectations of the lower level plus some indicators on the higher level. You’ll get that higher level when you show evidence of all of the skills in the next level.

No grading or scoring system is perfect, with each having different implications or issues to resolve. Many schools turn to hybrid models that still draw on some elements of A-F to appease the high performing students’ need for extrinsic motivation, but often undermine the school culture of learning. B21 is creating a scoring system that fully embraces their core values and is meaningful and motivational for both students who are chugging through the foundational skills they should have been taught in elementary school and those who are ready to accelerate through the high school curriculum.

Now, none of this made 100 percent sense to me the first, second, or even fifth time I looked at this. But it is starting to sink in – B21 wants kids doing their best, especially in the domains that are the most challenging. The design is guarding against the tendency of teachers to let kids slide when they show effort but haven’t quite hit the mark yet in learning. One of the students helped me understand this a bit more as she reflected, “I miss the As and Bs in ELA because I was good at it. However, the grading system has been really helpful to me in science and history because they are much harder for me.” You can read in detail these three guidelines on pages 7-12 of the Competency Handbook.

Crediting for Growth and Grade Level

The challenge faced by all high schools serving students who are under-skilled is how to help them build their foundational skills and award the high school credit required for graduation. Just imagine the frustration and demoralization of students when they find out that they need to build their skills from levels 6 to 8 before they can even begin to earn credit.

Although ideally, B21 would prefer to focus only on student progress, they have tackled the traditional system’s credit requirements with a two-tiered system for converting competencies to credits. They have created a conversion table between the average performance level in a course (the Average Performance Level) and grades. To be awarded a credit, students need to provide adequate evidence for each competency for the grade level at a Minimum Average Performance Level. To get credit, students must be no more than half a level below the performance/grade level. For example, if my Minimum Average Performance Level is 8.2 I’m not going to be able to be awarded a ninth grade credit, but I will get the credit if it is 8.5 or above.

But what about the under-skilled students working to complete sixth, seventh, or eighth grade? B21 has also created a growth model in which students can gain credit if they show 1.2 years or more of growth for all the competencies for which they did not earn the Minimum Average Performance Level. Now you can quibble about the details, but the overall concept is powerful. We should begin to think about ways to get this concept into policy so that students who have been tragically (and I would say) horrifically under-served by our public education systems have a meaningful pathway to graduation. This strategy offers a motivating method to get the extra effort on the part of students who may feel helpless and overwhelmed.

B21’s formula for determining growth is the difference between the first rating and the average of the last ratings earned for all the skills of a competency. Receiving a credit for growth means students will receive a lower grade than if they met the actual performance levels for each of the competencies.

Moumoujis explained, “Students aren’t self-paced at B21. If they enter with gaps, then we work with them to create a personalized growth pathway. Their pace needs to mirror their plan so they are in their zone and on a path toward graduation. If they can get adequate growth per year we can get them on track to being college ready.”

Similar to any competency-based school in a district that is supporting innovation but hasn’t made the transition to creating a comprehensive competency-based system, B21 encounters many bumps, especially related to time-based submission of grades.

Reflection: B21, like many competency-based schools, wants students to be able to earn honors without being tracked into an honors course. For students progressing above grade level, they can earn Advanced and Honors credit, with the accompanying higher weights, by earning .25 and .5 respectively above their grade level. However, B21 has hit a bump with state policies requiring them to roster students in honors courses at the beginning of the semester. Let’s put this on the list of state policies that need to be updated for a competency-based world.

Instructional Choices

A tenth grader explained to me, “I came here to be able to express myself. I wanted to have choices that I can’t get in regular public schools. I’m interested in technology, especially hardware.” B21 expects students to “design their own learning and have choice and voice in how, what, and where they learn.” Advisors “meet on a regular basis with individual students to set and revisit goals, reflect upon successes and failures, and track progress. Advisors will also support students in designing their learning pathways to ensure students are choosing instructional opportunities based on interest as well as competencies needed for graduation.” Below is a quick summary of the instructional model:

- Studios are learning experiences that are designed around a set of competencies. Every studio starts with a problem frame and ends with a culminating performance-based assessment and exhibition. Studios can vary in length, usually lasting between 6-12 weeks. Studios are comprised of modules that are independent but interrelated learning experiences that are necessary components to complete the culminating performance-based assessment.

- Modules are independent units designed around competencies. The learning that takes place in each module is necessary for students to complete the culminating performance-based assessment. The number of modules in each studio can vary depending on the length of the studio. A module is typically designed to help students master a particular skill needed to address the original problem frame of the studio. A module consists of a playlist of activities that is similar to a weekly lesson plan.

- Community Partnerships with local community organizations allow students to achieve competencies by participating in community based-learning activities such as art, music, recreation, and culture.

- Internships in local businesses allow students to achieve competencies through practical work experience and gain exposure to career options.

- Online Courses are available to gain content skills and knowledge necessary for demonstrating proficiency in needed competencies.

- Dual Enrollment allows students the opportunity to get a head start on their college careers, obtain an associate’s degree, and prepare for the transition to college.

Each instructional learning opportunity (or course) is designed around competencies and levels. As explained above, to get a credit, students have to meet the evidence requirements (tasks or projects in which students practice or demonstrate performance) of the course and earn the minimum average performance level. A ninth grade course has an average of 8.5, which means students have to be demonstrating performance levels pretty close to Performance Level 9 (100 percent Level 8 and some of 10). If the MCA isn’t high enough, it means the student isn’t at grade level…yet.

What’s important to remember is that the MCA is calculated with the average of the best rating. Students can always go back and improve their work or complete new tasks to replace the lower ones.

You might find some of Building 21’s resources on competencies for teachers and instructional design helpful. FYI – they are works in progress.

Strong Partnerships

B21 has been able to take the time to learn, reflect, and design through funding from the Next Generation Learning Challenge and Carnegie Corporations Opportunity for Design. The Office of New School Models at School District of Philadelphia has also been an active partner in working with B21 and other innovative schools to begin to build the structures that one day might become part of a district strategy. ReDesign and Springpoint have both been thought partners in creating the B21 design.

What’s Possible

The structure that B21 is setting up makes it much easier to think beyond what we know as schools and schooling. Gaffey explained, “Age-based structures are mostly not needed once there is a competency-based education model in place. A studio can potentially have and will start to have students of different ages and different performance levels. For example, if a studio will focus on civil rights and police brutality and one of the performance tasks is to write an argumentative essay, then students of different ability levels can participate in the same studio because the continua is completely disconnected from content. A student in their first year trying to get an average of 8.5 will fall in the lower continua and a student in their third year trying to get a 10.5 will score higher. Because we think in 6-12 week studios rather than in terms of year-long courses, students can start to pick experiences based on content and competencies. At scale, we will hopefully have enough opportunities running for students to design their own pathway through the competencies by picking studios they are interested in.

“Now…

“Imagine we get really good at this and no longer expect these experiences to happen between the walls of one particular school. Imagine a network of studios happening across a city. What if we could break down the school from a building and build school into a set of definite experiences that can happen anywhere? The CBE model allows us to do this, potentially with complete fidelity.”

Concluding Thoughts

Building 21, as all competency-based schools, has to translate between their innovative student-centered model and that of the time-based model, including translating to credits and GPA, following state requirements to roster students for honors, meeting district timelines for turning in grades, and, of course, passing grade-based accountability exams. There are also issues impeding implementation of the model that can be found in most under-resourced big city schools. Thus, we may not see full implementation of the model for a couple more years (and I’m sure they will continue to work through the kinks along the way). Fingers crossed that Pennsylvania takes a big step forward to create more innovation space for Building 21 and the other schools in the state that are pushing the envelope so that we could see what is possible.

Disclaimer: I’m an advisor to Building 21.

See also: