Central Academy, West Ada School District

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the ninth post in a series on Mastery Education in Idaho. Links to the other articles in the series can be found below.

“I was badly behind. No teacher would ever stop to help me. I even had a teacher scream at me once when I asked a question. It’s different at Central. They listen. They walk me through things. They make sure I understand. I’ve gained confidence. And I’m more motivated. Even though I am only a sophomore I have enough credits to graduate,” explained a student at Central Academy in West Ada School District.

West Ada School District is one of the ten grantees of Idaho’s mastery pilots. Its plan is to draw on Marzano’s High Reliability Schools approach for its high schools and to transform three alternative academies — Central, Eagle, and Meridian — into mastery-based approaches. Before I begin the description of the conversation at Central Academy, let me begin by commending West Ada’s vision for offering a range of high quality schools designed for students who are ill-served by the comprehensive high school. Too many districts only offer a minimum of alternative schools with minimum expectations for students, whereas West Ada understands that a commitment to serving all students means offering a range of models and opportunities to meet the needs of all students.

Central Academy’s instructional coach Nichole Velasquez is an enthusiastic supporter of mastery-based learning, “There is so much more self-accountability in the mastery-based system compared to the traditional one. How have we ever been this granular and targeted in our feedback and instruction before? It makes a huge difference for students when they receive feedback on what they need to do to fully learn something. I love what I’m doing.”

Central doesn’t feel it needs to invent the wheel. They are drawing from other organizations as they move through their implementation plan. They are working with Building 21 and Bronx Academy, two schools that have designed around the need of teenagers who are entering high school or returning to high school with gaps in knowledge and few credits, to reconfigure their model.

Culture

Velasquez explained that principal Donell McNeal “promotes a culture of safety, humanity to explore what makes a good human being, effective teaching, and a future focus on college and career readiness.” She noted that McNeal had been a counselor before he was a principal and brings that orientation to his leadership. She added, “Donell sees every conversation with a student as an opportunity to reinforce skill development.”

A strong feature of the culture at Central is restorative practices. They have turned to a book called Better than carrots or sticks: Restorative practices for positive classroom management. Velasquez noted that behavioral issues are on the decline. She enthusiastically added, “Teachers have done a great job shifting the culture toward building restorative relationships with students.” I found this comparison of restorative approach to a non-restorative approach (what would we call that – punitive?) very helpful.

Pedagogy

Several years ago, Central made the shift to blended learning using a model in which teachers provide direct instruction with much of the content online. They originally had a curriculum from the Idaho Digital Learning Academy, but found it difficult as teachers weren’t able to modify it and it wasn’t aligned to competencies (i.e., higher order skills).

The shift to mastery is renewing the focus on instruction. Velasquez said, “Mastery exposes our weaknesses. I could stand up and deliver curriculum, but they might not be learning anything. Mastery-based education creates internal accountability. We have to constantly ask ourselves ‘Are kids learning?’ And it exposes where we need to learn when they are not.” I had a sense that this was causing agitation for some educators, as several suggested that they “have always been doing mastery.” This position is not what I usually hear from teachers in competency-based schools. In fact, it is the exact opposite, with teachers usually sharing what they are learning and what they are excited about. They also say it has meant that experienced teachers suddenly find themselves feeling like new teachers all over again. That’s not always a good feeling, especially when teachers in alternative schools face the enormous challenges of helping students build the academic and emotional skills that should have been developed in elementary school.

I had the opportunity to watch a math teacher work with seven students, each with a small handheld whiteboard, to learn how to change a fraction to a decimal. (Yes, it is shocking that a high school needs to teach this, but when students are passed on without actually learning, this is the result.) He was able to see how students were solving the problems and then provide appropriate feedback, hints, or questions to help them understand their missteps and misconceptions. He also often reminded them that they had the skills to do the problem, and that they can be confident and believe they can be successful. Later, the teacher explained how he uses hands-on activities to help students understand how the math is useful and how it becomes alive in the real world.

There is a strong emphasis on reflection in the cycle of learning used by Central: engage, explore, practice, apply, and reflect. This is particularly important in helping students understand how academic success is dependent upon the habits of success.

The next step in strengthening instruction will be focusing on learning strategies in mini lessons to ensure skill acquisition including meta-cognitive strategies and reading comprehension strategies. They will also be seeking to integrate Jim Knight’s High Impact Instruction strategies.

Structure

Central has made a number of structural changes that create transparency of expectations, multiple feedback loops on student progress, and strategies to meet students where they are academically and emotionally.

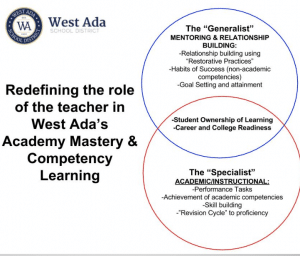

Staffing: After visiting Bronx Arena, Central has changed their staffing patterns to have generalists and specialists. There are mentors (many of whom are special education teachers, as half of the students at Central have an IEP or 504) building relationships with twenty to twenty-five students. At the beginning and end of each day, generalists hold restorative circles for personal reflection, check-ins, and opportunity to address important aspects of learning and development. The other role, instructional specialists, work with students individually or in small groups in response to students’ personal learning plans and where they might need more support. Students have started creating their own schedules to see instructional specialists. One way to think of this is as generalists meeting students where they are emotionally and specialists meeting students where they are academically.

Velasquez emphasized, “We have A-HA! Moments all the time. Something will happen with a student. There will be an emotional outburst of one kind or another. We try to understand what caused it and, most of the time, it goes back to one of the social-emotional skills. For example, students often give up too soon or get very frustrated when something doesn’t come easily. Then they feel bad about themselves and their confidence is undermined. This means we need to work with them on building perseverance.” The team at Central started paying attention to adverse childhood experiences (ACES) and learning about trauma-informed care after seeing the film Paper Tigers. “We are becoming more intentional in helping students build social-emotional skills. However, this is changing the teacher role. Teachers are learning at their own pace about how to better support social-emotional learning.”

Velasquez emphasized, “We have A-HA! Moments all the time. Something will happen with a student. There will be an emotional outburst of one kind or another. We try to understand what caused it and, most of the time, it goes back to one of the social-emotional skills. For example, students often give up too soon or get very frustrated when something doesn’t come easily. Then they feel bad about themselves and their confidence is undermined. This means we need to work with them on building perseverance.” The team at Central started paying attention to adverse childhood experiences (ACES) and learning about trauma-informed care after seeing the film Paper Tigers. “We are becoming more intentional in helping students build social-emotional skills. However, this is changing the teacher role. Teachers are learning at their own pace about how to better support social-emotional learning.”

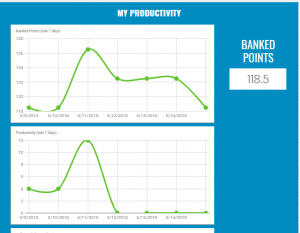

Personal Learning Plan and Points: Whereas many competency-based schools separate out the academics from behaviors in grading policies, Central is taking a step further in formalizing the behavioral arm of learning. Central has also adopted Bronx Arena’s point tracking system. The points are based on productivity in terms of submitting evidence of learning and habits of success. They are designed to provide points for effective effort as a way of helping students build those skills as well as extrinsically motivating them. From what I could tell, this meant helping students, or at least some, have a sense of success and pride even when they were still far from graduating. The PLP points were providing a shorter-term sense of success as students worked in the longer term to gain credits on the way to graduation. I couldn’t help remembering one point in the discussion on developing the logic model for competency-based education when a researcher reminded us that sometimes extrinsic expectations and motivation are internalized over time.

Velasquez said that teachers love the point system and that it has become a powerful tool for monitoring students. She explained, “When students are having a hard time outside of school, they may come to school but not be able to focus very effectively. The PLP Points tracking allows us to know what is happening with students. If there are few points over a number of days we call a meeting with teachers, parents, and the student.” Thus, Central is thinking about pace as an indicator of effort.

I can imagine CBE educators might have mixed feelings about using such an extrinsic motivational strategy. However, even credit completion becomes a form of progress tracking when credits are the proxy for learning. Central, like most any school designed to help students reach graduation when other schools may have given up on them, are designed around credit generation and credit tracking. However, they are equally focused on the development of competencies. Reflection: I would love to see an alternative school designed for over-age and under-credited (this term being deeply rooted in a time-based orientation) students that was only organized around building knowledge and skills. What might it look like if the focus was solely on learning?

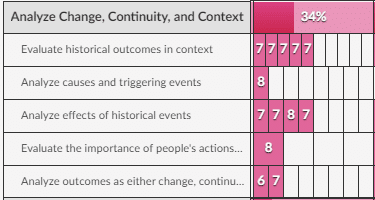

Competencies and Habits of Success: Central has adopted Building 21’s competency framework and its dual approach to monitoring both growth and grade level proficiency. Velasquez explained, “Growth is really challenging for teachers. Some teachers have a hard time getting beyond A-F grading and grade level standards. But we want to look at the continuum of where students are in their learning and how they are advancing. In order to succeed in a mastery-based environment, teachers have to develop a different understanding of accountability. It isn’t about reducing points for late work. As teachers, we need to become accountable for helping students understand the value of putting forth the effort toward learning.”

She added that people find themselves learning and changing once they have started working in a mastery-based environment. She explained, “My 14 year old told me the other day that she was glad I was doing mastery work because I’ve changed. It’s true my perspective has changed. I have more clarity about what is important. The most important thing is whether she is learning or not.”

Central’s Habits of Success are described as the “characteristics of an independent learnerer”: growth mindset; decision-making; self-regulation; work and time management; and social skills and awareness.

Information System: One of the most fascinating parts of this site visit was the information system that is being developed in partnership with the team of Building 21 and Slate. They are integrating several types of data on learning to monitor student learning and progress. First, there are the PLP Points tracking submission of evidence and habits of success. Second, the development of competencies are monitored through the grading system. Third, credits toward graduation are tracked. A fourth set of information, with the content organized around competencies, sits within a Google site.

What’s Next for Central Academy?

Velasquez suggested that they would benefit from building their capacity for diagnostics so that they could more quickly understand what students know, don’t know, and where they have misconceptions that are causing them to stumble. They are also building out a Maker Space for students to do hands-on learning, discovery, and invention.

Read the Entire Series:

- Part 1 – Mastery-Based Learning in Idaho

- Part 2 – Finding Synergy at Kuna Middle School

- Part 3 – Moving Forward toward Mastery at Kuna School District

- Part 4 – Increasing Credits Earned at Initial Point High School

- Part 5 – Finding and Fixing the Missing Skills at Greenhurst Elementary School

- Part 6 – Columbia High School: How a Comprehensive High School Becomes Mastery-Based

- Part 7 – Gathering Insights on Mastery-Based Learning from Columbia High School

- Part 8 – Slaying the Dragon: A Conversation with Cory Woolstenhulme on Mastery-Based Learning

- Part 9 – Central Academy, West Ada School District

- Part 10 – The Sharp Ones: A Few Takeaways from Idaho