Deeper Student-Centeredness: Where Cultural Heritage and Mastery-Based Learning Meet

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post about the importance of cultural heritage originally appeared in December 2024 on the MBLC Community Site blog, which is part of the Washington State Board of Education’s Mastery-Based Learning Collaborative project.

In May I had the opportunity to speak with two exceptional Indigenous educators in Washington State about the interplay between cultural heritage and mastery-based learning (MBL). Robin Pratt, Native American Education Coordinator in the Auburn School District, and Sui-Lan Ho’okano, Cultural Support Program Manager in the Enumclaw School District, bring a combination of personal and professional experience to helping schools lift up the cultural heritage of their students. The conversations were a true gift: My eyes were opened up to a much deeper understanding of culture heritage and its power to shape our experiences. Below are a few highlights from our fascinating discussions.

Background: Combining Two Powerful Learner-Centered Strategies

The Washington State Board of Education (SBE) broke new ground in state policy when it designed the Mastery-Based Learning Collaborative (MBLC) to be rooted in both mastery-based learning and culturally responsive-sustaining education (CRSE).

SBE modeled the MBLC on New York City’s Competency Collaborative, a network of 80+ public K-12 schools that use both CRSE and competency/mastery-based, with guidance from Joy Nolan of New Learning Collaborative, co-founder and longtime Director of the Competency Collaborative. For the first three school years of the SBE’s MBLC, Nolan has served as a professional learning provider and school coach for the initiative.

“While equity is named as one of the 16 quality principles of mastery/competency-based learning, the field of mastery/competency education has been largely silent on how to recognize, value, and incorporate students’ racial, cultural, and social identities into learning,” says Nolan.

Like with any school change effort, MBL implemented without a clear focus on equity, will continue to reproduce achievement gaps. Systemic inequality and bias based on race, class, gender, and/or other markers will find a way to corrode improvement strategies. By laying the foundation with CRSE, SBE hopes to catalyze more equitable student-centered school culture and instruction, leading to positive outcomes for learners.

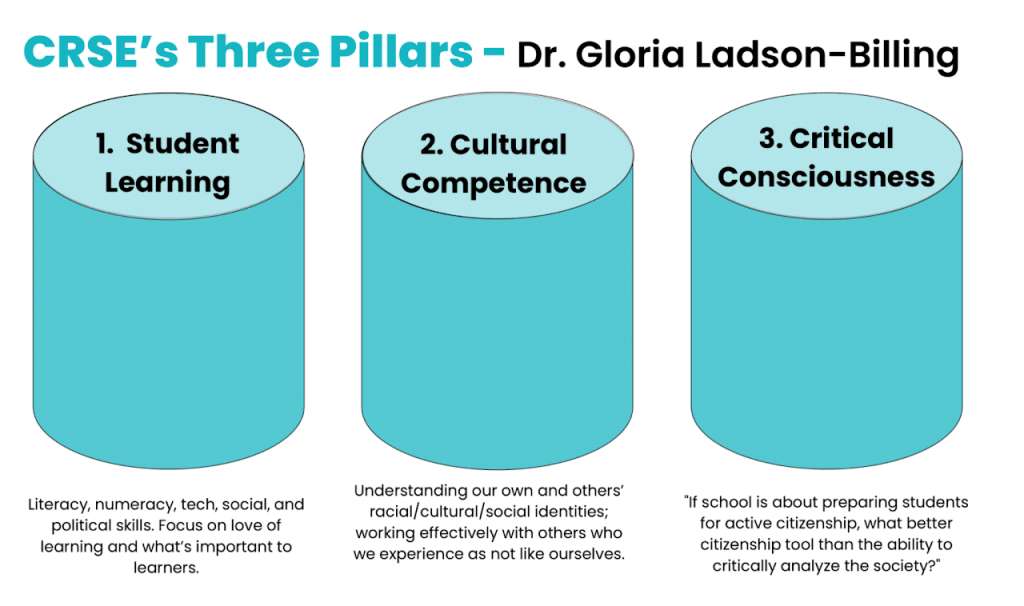

CRSE is grounded in the three-pillar Culturally Responsive Education framework developed by Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings:

“After Dr. Ladson-Billings offered her groundbreaking theory of CRE (Culturally Responsive Education) in the mid-90s, the field developed and evolved. In 2010, Dr. Geneva Gay brought in the concept of responsive pedagogy, saying that education needs to be responsive as well as relevant to young people’s racial and cultural identities,” says Nolan.

“In 2014, Dr. Django Paris and Dr. H. Samy Alim named the importance of sustaining learner’s identities, as well as being relevant and responsive—so we now have the current set of research and practices that is culturally responsive-sustaining education (CRSE)—all premised on Dr. Ladson- Billings’ original 3 pillars.”

CRSE as Scaffold for Learning

In the cultural tension that can bubble up in our communities, it’s easy to lose sight of why it’s important for schools to consider students’ cultural heritage in terms of student learning. There is plenty of research indicating that respecting and responding to students’ cultural heritage benefits all learners. However, science and research are frequently dismissed in the debates about education. So let’s look at some ways culturally responsive-sustaining approaches make a difference for student learning and wellbeing.

Every student carries their cultural heritage with them, whether schools recognize it or not. Ho’okano explains, “You can’t remove cultural heritage from a person. It is inherent in each of us. It’s who we are when we walk into the classroom.”

Pratt notes, “We can’t expect kids to shave off parts of their identity. Instead, we can create environments where it is cool to have culture and learn from each others’ culture; we can see cultural heritage as an asset.”

When students feel personally connected to the academic content, they can more easily tap into prior knowledge. Furthermore, academic knowledge and skills that feel relevant to students’ lives increases intrinsic motivation. That drive sparks students to strive for excellence, not just for the grades.

Ho’okano points out, “Fifty percent of the curriculum walks into the classroom, the other 50% is outside of the classroom. Learning occurs through experiences. When we allow learning in our schools to reflect students’ environments, cultural, and lived experiences, we lift up the plethora of knowledge they already come with. We create connections, students see themselves in the learning, relationships are built. When systems curricula and content is shared with the experiences of diverse cultures and environments, we begin to eliminate power dynamics between educators and learners, we provide access and opportunities for unrepresented learners to be seen, sought, heard, and listened too. As educators you eliminate the weight of thinking you have to carry this all on your own. You are in a shared learning experience that is beneficial for all.”

Furthermore, ignoring the cultural heritage of students is likely to cause harm, Ho’okano says. “If we aren’t lifting up students’ cultural heritage, we are doing a disservice. It suggests that there is no other knowledge than what is in the classroom. Instead of a teacher role modeling curiosity and exploration, it signals that learning is something given to you rather than something you discover yourself. Worst of all, it can maintain stereotypes and perpetuate oppressive systems. It signals that students don’t belong.”

It’s time to make room for a truce in our culture wars to do what is best for kids. There are too many benefits culturally responsive-sustaining classrooms benefit students—all students. “Even if you only care about academic performance, CRSE is a powerful scaffold,” Joy Nolan explains. “Student-centered learning is a popular movement right now. We can’t put students at the center unless we understand who those students are. If your goal is to put students at the center, you can’t disregard large parts of their reality, their identities, and their experiences.”

Exploring Commonalities Between Indigenous Ways Of Learning And Teaching And Mastery

Both Pratt and Ho’okano were drawn to join the Washington MBLC because of the similarities of the principles of MBL and Indigenous ways of learning. Pratt turns to the Circle of Courage, a youth development framework based in Indigenous knowledge, that highlights belonging, generosity, independence and mastery. These are very similar to the concepts of self-determination theory that describe the conditions to create intrinsic motivation: autonomy, mastery, and connectedness.

The Circle of Courage is foundational to the work in the Native Education program in the Auburn School District. Instead of pulling students out to do extra worksheets where they are struggling, Pratt and her colleagues seek to form respectful relationships and connect students with the things in their lives that are important to them. Drawing upon MBL practices, they look for ways for students to earn credits for learning and applying academic skills in real-world experiences such as working at a tribal wildlife office, speaking publicly in front of hundreds at a pow-wow, or navigating a waterway in a canoe they made themselves.

Pratt encourages educators to understand how students are participating and demonstrating leadership in their families and communities. She says, “Students may be bringing funds of knowledge into the classroom about fishing, weaving, and community organizing. It’s a real loss for everyone if teachers don’t take the time to get to know their students. Watch out if students don’t have belonging, autonomy, meaningful ways to show their learning, and opportunities to contribute. It’s likely there will be some reaction such as defiance.”

It can be very frustrating to cultural practitioners to hear effective instructional strategies such as MBL framed as new and innovative. After centuries of having been told that Indigenous culture and practices were wrong-minded and primitive, American education is now embracing those very same concepts that are at the heart of Indigenous educational strategies. Ho’okano explains, “ MBL has worked for Indigenous communities for centuries before the efforts to replace it with a system that demanded memorization and compliance. At its essence, MBL is drawing upon the very practices that Indigenous communities have been using since time immemorial. Interdisciplinary learning, learning by doing, transfer of knowledge, rigorous ways of knowing and being are all part of our traditional practices.”

Nolan agrees, “The field of MBL as it has developed over the last 15 years is largely white. It developed primarily in white communities. When we began doing this work 10 years ago in New York City schools serving a diverse array of students, it soon became clear that MBL was missing a key element: culturally responsive-sustaining education. Sui-Lan does us a great service by asking us to consider that MBL owes a great debt to Indigenous education practices, as Robin does by connecting MBL to the Circle of Courage.” That’s why it is important to humbly recognize that MBL is a comprehensive approach that is grounded in what Indigenous cultures have always known as well as the growing body of research about how we learn.

There was one area where there seemed to be some difference between the discourse in the field of MBL and the Indigenous perspectives brought by Pratt and Ho’okano. Whereas the goal of MBL is the achievement of individual students, Pratt and Ho’okano often referred to the process and purpose of education as the wellness of the community. Their experiences and those of their ancestors would rightfully place survival, strength and self-determination front and center.

There are places in MBL where the value of community well-being can be found. For example, in many schools, teachers take the time to cultivate communities of learners where students are dedicated to the success of each other. In addition, there are districts that are creating Portraits of a Graduate that emphasize the importance of being able to collaborate, value diversity and take leadership in solving community problems. However, most of the MBL field focuses on student achievement and college readiness.

CRSE offers a bridge. The designers of CRSE, Dr. Ladson-Billings, Dr. Gay, Dr. Paris, and Dr. Alim, see education as a method to prepare students to be active citizens in a democracy. Zaretta Hammonds, author of Culturally Responsive Teaching and the Brain, also advocates for preparing students with the skills to understand interdependence and work collaboratively. When you consider the lifelong skills highlighted in Portraits of a Graduate, cultural competence and critical consciousness are important skills all students need for working together towards addressing complex community issues.”

Deepening our Understanding of Student-Centeredness

One of the big shifts happening in education is moving from a teacher-centered approach to a student-centered approach. This effort involves more active learning, high engagement and interest-driven learning experiences and increased responsiveness. Nolan explains, “We aim to make school more welcoming and effective for each learner. We seek to make school a place of belonging, discovery, and growth—so that every student will feel like their school is for them, in as many ways as possible. We want them to experience/assume their school is for them and other kids like them, rather than their attending a school every day that feels like it was made for someone else.” As I listened to Pratt and Ho’okano, I began to wonder: Is the field of education missing some important elements of what it means to be student-centered?

- Bringing Your Whole Self: Pratt and Ho’okano argue that it is imperative that students bring their whole self to learning. This means that our schools and educators will need to be very comfortable getting to know students who may have very different experiences and cultures. They’ll need to think about how to support students in their lived experiences, not just those in the classroom—this is the essence of cultural competence. Ho’okano clarifies, “No one is expecting every teacher to know everything about every culture of the students in their classroom. Rather we hope teachers are asking the question: What can I learn from my students? What might they know or think about that can teach me and the other students?”

- To what degree are schools shifting to student-centered creating school cultures that celebrate their children and teens for their unique selves including their cultural heritage? Are advocates including identity development and cultural heritage as part of defining and measuring student-centeredness?

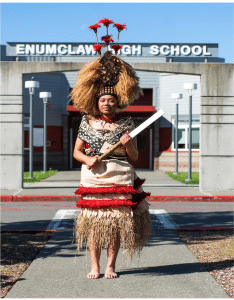

Photo courtesy of Enumclaw High School

- To what degree are schools shifting to student-centered creating school cultures that celebrate their children and teens for their unique selves including their cultural heritage? Are advocates including identity development and cultural heritage as part of defining and measuring student-centeredness?

- Relationships: Indigenous ways of learning and teaching assume that those doing the teaching are in relationship with the students. Certainly, the mantra of relationships, rigor and relevance has been chanted in education for over 30 years. However, in too many high schools, teachers have 150 students in their classrooms each week with new ones flowing in the next semester.

- Can schools be student-centered if teachers don’t have adequate opportunities to build relationships with their students? What is preventing us from organizing our schools so that relationships are prioritized?

- Belonging: When students are able to bring their whole self and relationships are in place— requiring a combination of comfort/familiarity, caring, respect, trust—students feel that they belong. They are part of the community, not ‘other’ or ‘outside.’ Nolan emphasizes, “Integrating CRSE and MBL strengthens both frameworks. CRSE-MBL seeks to foster both wellbeing and academic success. Even if you only care about academic growth and success, attending to wellbeing and belonging is a powerful way to get there.”

- Is the goal student-centered or student-empowered? Do we want to make decisions about students or have mechanisms in place where students are taking responsibility for their education and the well-being of the community?

Pratt cautions educators that to be student-centered is to always remember that children and teens are much more than just students. They have rich lives with robust learning taking place outside of school. Pratt says,“MBL is about demonstrating what we are learning no matter where we learn it. That means we are bringing the inside out, and the outside in. Students shouldn’t have to give up the ‘real world’ to learn in school. Nor should they ever be asked to give up part of themselves.”

In Closing

As Pratt and Ho’okano shared their beliefs, perspectives, and knowledge, I had moments when it felt like mainstream culture was being peeled back so I could see it more clearly. Ho’okano sprinkled Hawaiian concepts along the way that required me to pause and in most cases shifted my perspective. For example, kuleana is a term that means that once you have knowledge you are responsible for passing it on. What a difference it would make if instead of running home to tell my parents that I got an A, I might have thought about how I might pass the knowledge on to someone else.

One of the most powerful was the concept of kaona, which is best understood as the hidden meanings in words and phrases that are to be discovered. Certainly, this conversation about cultural heritage has left me brilliantly aware that I still have much more to uncover. I am left wondering a series of important questions: How might my own cultural heritage be leading me to overlook or underestimate possibilities of what a high quality mastery-based system might look like? How might mainstream culture be getting in our way of transforming schools? If I increased my awareness in other cultures how else might my perspectives shift and my understanding deepen?

The leadership of Pratt and Ho’okano and the efforts of the Washington MBL Collaborative fill me with hope. With each day, and as more states and districts embrace the importance of cultural heritage and culturally responsive-sustaining education, we will create more and more room for students to bring their full selves and their full curiosity.

Learn More

- School and State Transformation in Washington: Lessons from the Mastery-Based Learning Collaborative’s First Three Years

- Voices of Indigenous Educators Series: “We’re all in this canoe together.” – Sui-Lan Hoʻokano

- A Primer to Indigenous Education: A Case for Tribal Competency Crediting

Chris Sturgis is principal of LearningEdge, a consulting firm advocating for aligning schools with research on learning.