Entry Points: Moving Toward Learning-Centered Practice

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the fourth post in a ten-part series that aims to make concepts, themes, and strategies described in the Moving Toward Mastery: Growing, Developing, and Sustaining Educators for Competency-Based Education report accessible and transferable. Links to the other articles in the series are at the end of this post.

This is the fourth post in a ten-part series that aims to make concepts, themes, and strategies described in the Moving Toward Mastery: Growing, Developing, and Sustaining Educators for Competency-Based Education report accessible and transferable. Links to the other articles in the series are at the end of this post.

“Development is a process, not a destination. Learning spans the course of a lifetime, and professional development spans the course of a teacher’s career as they try, test and extend new practices that help them improve student learning and advance equity. Like learners, teachers pursue learning progressions along competency-based pathways and are met where they are with timely, differentiated supports. Their personal learning is rooted in student learning and closely connected to improvement at the team, school and system levels. Competency-based approaches are supported by growth-oriented and flexible systems of support, feedback and evaluation. For students and teachers alike, teaching and learning are grounded in meaningful demonstrations of learning rather than seat time.” – Moving Toward Mastery, p.35

To adopt new practices and improve their instruction, teachers need to learn. Simple, right? And yet this often does not happen in the traditional education system. The majority of “learning” happens during teacher training. After that, most formal “learning” is constrained to mandatory professional development, while the on-the-job learning that teachers do on their own is rarely recognized, supported, or evaluated. The end result is that much time and money spent on professional development activities may do little to improve teachers’ knowledge or skill. This is a problem for any system trying to improve teaching and learning. It is a particular problem for systems trying to navigate the shift to competency-based education, because this shift requires so much learning for teachers.

So, what would it look like if education systems addressed these challenges of professional learning for teachers? And, how can you cultivate these conditions in your school or district? The next three paragraphs paint a vision of what a learning-centered system would look like. After that, I offer tools to help leaders and teachers assess learning practices in their school or district and identify entry points for action.

Vision

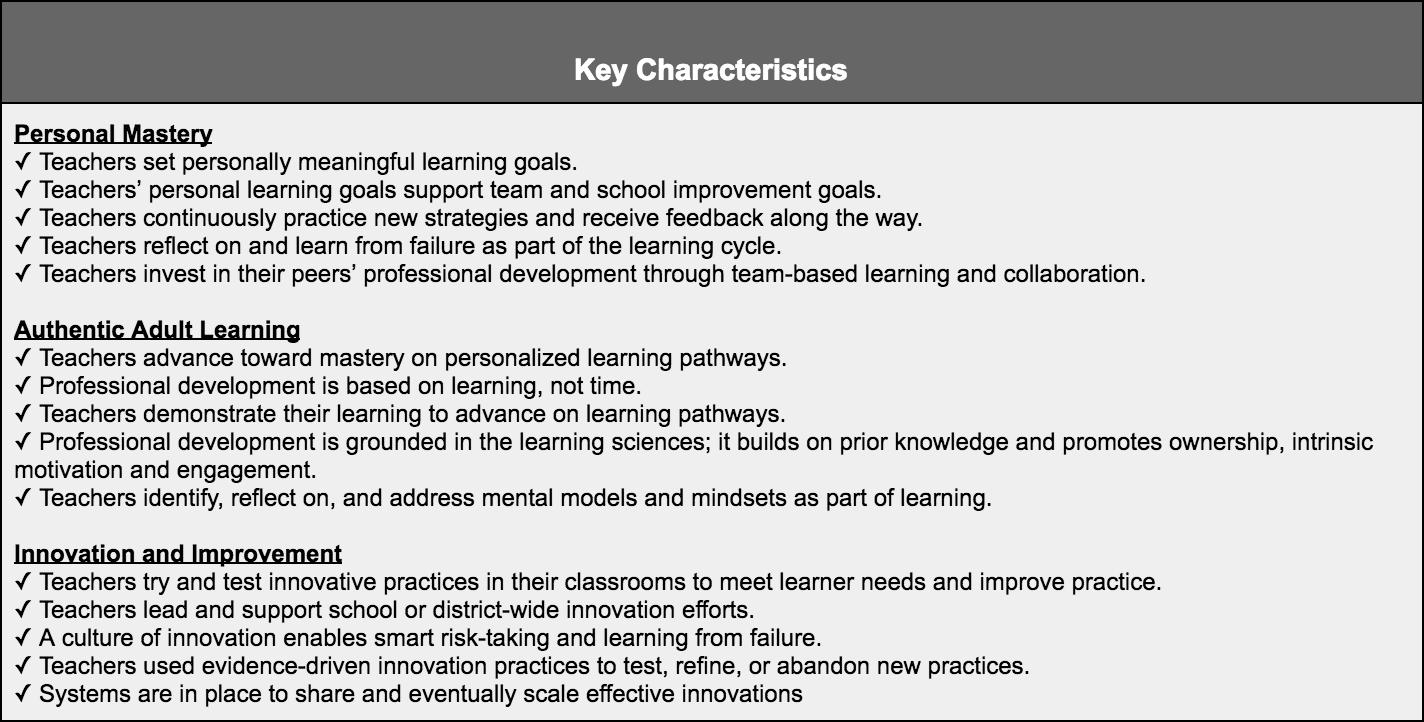

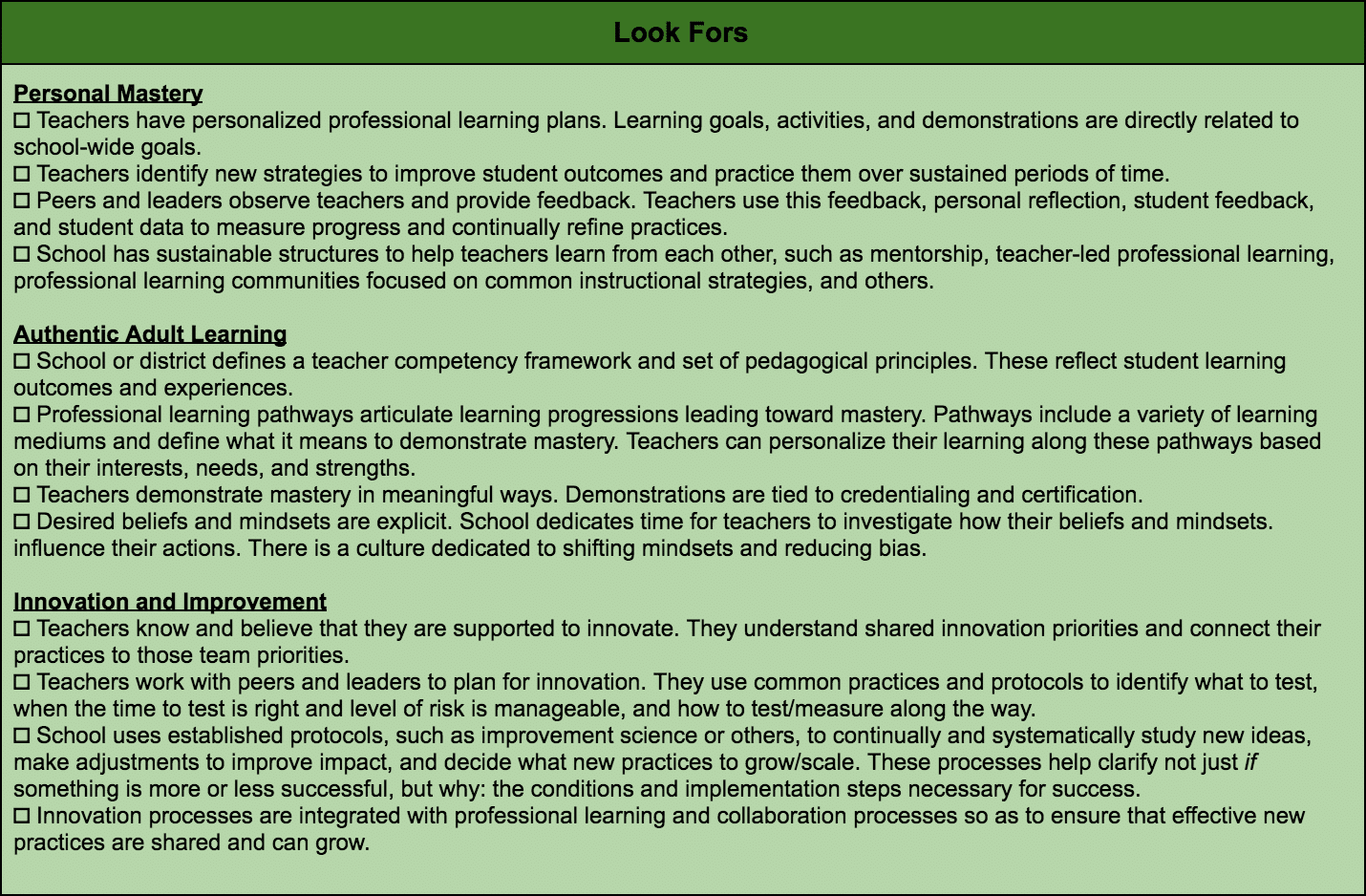

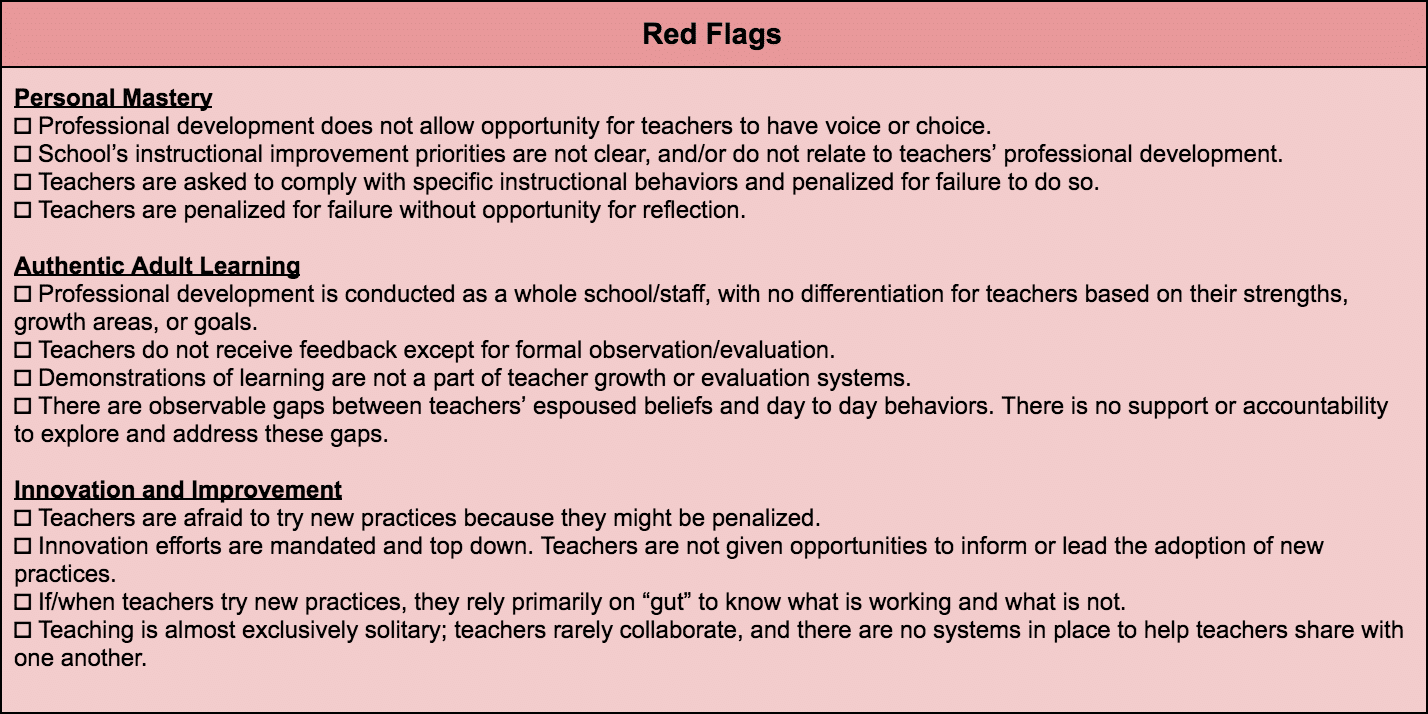

Learning develops personal mastery. In his book The Fifth Discipline (1991), Peter Senge describes personal mastery this way. “People with a high level of personal mastery live in a continual learning mode. They never ‘arrive.’ Sometimes, language, such as the term ‘personal mastery,’ creates a misleading sense of definiteness, of black and white. But personal mastery is not something you possess. It is a process. It is a lifelong discipline. People with a high level of personal mastery are acutely aware of their ignorance, their incompetence, their growth areas. And they are deeply self-confident. Paradoxical? Only for those who do not see that ‘the journey is the reward.’” What could this mean in education? To me, the idea of personal mastery would translate to education in one big way: it would mean recognizing that teachers are constantly learning and developing on personal pathways, and helping them do so.

Learning improves practice. In Getting to Scale with Good Educational Practice (1996) Richard Elmore explains how practice (observing and trying and testing new approaches) helps improve practice (instructional quality and student learning). “Teachers are more likely to learn from direct observation of practice and trial and error in their own classrooms than they are from abstract descriptions of new teaching. Changing teaching practice, even for committed teachers, takes a long time, and several cycles of trial and error. Teachers have to feel that there is some compelling reason for them to practice differently, with the best direct evidence being that students learn better. And teachers need feedback from sources they trust about whether students are actually learning what they are taught.” Here’s how I’d boil this down: if you want to help teachers change their daily actions, give them time and space to practice, give them feedback, and give them the opportunity to see (and then believe) that the changes make a difference.

Learning enables innovation and improvement. When you are shifting to competency-based education, you are asking teachers to try things that will seem radical. That’s innovation. When you are growing and sustaining competency-based education, you are asking teachers to continually adjust and refine what they do. That’s improvement. Innovation and improvement are constant states of being. To create those states of being requires specific cultural, learning, and structural conditions. In Reciprocal Accountability for Transformative Change: New Hampshire’s Performance Assessment of Competency Education (2017), the authors describe innovation and improvement this way. “Our teachers’ role was to embrace the uncertainty that comes with stepping out of their comfort zones, committing to working collaboratively with colleagues, and sharing our learning to benefit all.”

Tools

Key Characteristics, Look Fors and Red Flags

Reflection Questions

- Where are we in our practice today? Where are we on the continuum?

- Where do we want to be? What can equity-oriented practice look like in our system?

- What are we doing well that we can build on? What strengths can we leverage?

- What are we doing that will get in our way? What barriers will we need to address?

- Where can we begin?

- Who do we need to include in this work?

Read the entire series:

- Introducing Moving Toward Mastery

- Entry Points: Moving Toward Equity-Oriented Practice

- Voices: Developing Teacher Mindsets

About the Author

|

Katherine Casey

Katherine Casey