How Being in a Competency-Based Learning Environment Prepared Me for College

CompetencyWorks Blog

My senior year of high school was big for me: AP classes, two internships, leadership roles in clubs, and a spring musical. Yet, despite those things, only one stressor truly haunted my mind: where I would go to college the following year. I attended Kettle Moraine School for Arts and Performance (KM Perform), a competency-based learning environment, in Wales, WI, for high school, and I wanted a similar experience for college. So naturally, my laundry list of possible colleges included primarily small, private, liberal arts colleges with comparable learning environments. It was a shock to all (myself included) when I chose the University of Wisconsin-Madison, a large state school, to continue my education.

Going to college is a big adjustment for any student in more ways than just attending (and passing) classes. The excitement of new people, places, and things can be overwhelming. As a rising junior, I am still learning new things, seeing new places, and constantly meeting new people. On a Friday afternoon during my freshman year, as I discussed football games and upcoming weekend plans with new friends, I received a 67% on my first midterm. I was devastated. I didn’t understand what happened; I did everything I was supposed to: quizlet, practice questions, and re-reading our two ginormous textbooks. I even followed my professor’s study guide with terms to know and concepts to understand. Many adults from my hometown had been skeptical about competency-based learning environments adequately preparing students for university, and it was something my family and I had considered when I enrolled in high school. Had I made the wrong choice?

Making Sense of My Midterm

At KM Perform, we did not take tests. In fact, my ACT was the most recent test I had taken before my first midterm. Instead, we presented our learning through projects and hands-on experiences. Rarely did I ever fill in a circle with a number two pencil or circle “true” or “false.” I expressed my fear to my roommates and discovered I wasn’t the only person who had done poorly on my first exam. All four of us had. Upon further conversation with peers in my class, I found out many more could have done better. While I wasn’t the only one who had done poorly on the exam, I was undoubtedly the only one who attended a competency-based learning environment.

I only had a little experience demonstrating my learning through exams, but there were other ways I had presented knowledge throughout high school. So I began using those experiences and skills to my advantage instead of trying to reorient myself to a traditional banking model of education and losing many of the skills I left high school with. Kettle Moraine School District created a graduate profile that requires all students to graduate with the following skills: Continuous Learner, Communicator, Collaborator, Creative & Critical Thinker, Engaged Citizen, and Self-Directed & Resilient Individual. Whether you’re good at Algebra or struggle with US History, these graduate-profile skills translate across all academic and real-life situations.

Putting My Graduate Profile Skills to Use

At a school with 30,000 students, you must advocate for yourself. Being in university quickly affirmed that just attending a class in a lecture hall with 500 students isn’t enough. Class participation, asking in-depth questions, creating in-depth projects, and communicating with faculty and colleagues set you apart from 500 other students. Education needs to prepare students to be able to do that successfully in their post-secondary careers, which involves having a diverse skill set like Kettle Moraine’s graduate profile.

In my political theory class, we had weekly discussion sections that we were expected to attend and participate in. Some activities included regular discussion, group work, and occasional role-playing as different political theorists. While other students looked like deer in headlights when asked to do these tasks, I had already been doing activities like this for years. My professor was so impressed with my participation in the discussion section and lecture that he told me I had shown him I knew the material and that I didn’t need to take the final exam. Getting a 67% in my other class, to say the least, sucked. Tears were undoubtedly shed, and my roommate most certainly needed to talk me off the ledge of returning to my hometown job. Despite this, having skills like thinking creatively, communicating effectively, collaborating with others, and advocating for yourself are crucial tools for post-secondary success, both academically and socially, and can help you in some of the least expected ways.

Hope for Higher Education

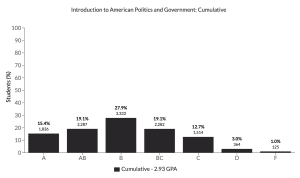

Later, I discovered that only 15% of the class I got my first (and only) 67% had finished the course with an A. I finished with a B, which was pretty average for the course. While highly knowledgeable and respected, my professor preferred a more traditional banking approach as his teaching style. The only way we demonstrated learning was through multiple-choice tests. My only audience was a scantron.

The most confusing part of the class was that 60% of us got less than an AB (UW-Madison’s version of an A-) in Introduction to American Politics in Government. Admittedly, I went into it a little overconfident (I thought I could do it with my eyes closed), but I failed to understand how most of the class did poorly. Everyone in the class had resided permanently or temporarily in the United States to attend UW-Madison. American politics and government affect each of us every day differently. Yet, our collective, experience-based knowledge was disregarded and not valued during the entirety of the course. Instead of learning from each other, fostering new discussions, and finding new perspectives, we memorized the same topics most of us likely covered in our U.S. elementary, middle, and high schools. Despite repeating this topic for 12 years, many students didn’t do well in the course. What does this say about our current education system?

Since my first semester, I purposely try to take classes where it looks like tests aren’t involved (because…how boring, right???), but I have taken courses since then that are more test-driven. Not just using resources like Quizlet and readings to study but also communicating through office hours, collaborating with others, and creating my own practice problems have helped me tremendously in test-driven classes. Despite this, we are starting to see changes in higher education. At UW-Madison, most lectures are accompanied by a discussion section incorporating skills like communication, collaboration, critical thinking, and creativity. Without this skill set going into college, more challenging to succeed in discussion sections.

Additionally, I have noticed many professors asking students to do projects, craft essays, or have hands-on experiences to demonstrate learning objectives designated to the course. Most recently, in my Education Policy course, our teacher presented us with a final project worth 30% of our grade. She explained the assignment description to us, in which the expectation was to create a real-world application of our knowledge of social justice in education, and provided a rubric that defined the assignment’s expectations. So many students in my class, including many future educators, were taken aback by this like it was something they had never been asked to do before (This was what every day looked like in KM Perform). If there isn’t an expectation for high schoolers and undergraduates to create real-life application projects, what does this mean for their future?

The Final Verdict: CBE or Traditional Learning?

Before I went to KM Perform, I had little confidence in myself. I had difficulty speaking in front of large audiences, participating in class, and working with others. However, the nature of competency-based learning pushed me to work on these skills, which have prepared me tremendously for my post-secondary education. Even though many colleges are very test-driven and data-oriented, that doesn’t mean that the skill sets mentioned in Kettle Moraine’s graduate profile, and other skills created through competency-based learning, aren’t valuable during and after post-secondary education. Despite UW-Madison’s semi-traditional model of education and my upsetting 67% from freshman year, I have earned myself a spot on the Dean’s list every semester since and am involved with many extracurriculars and groups on campus. These skills have helped me navigate many different areas of my post-secondary career and will continue to help me throughout the rest of my life. I am the student I am today because of my competency-based learning experience, and I am excited to see where CBE takes other students in the future as well.

Before I went to KM Perform, I had little confidence in myself. I had difficulty speaking in front of large audiences, participating in class, and working with others. However, the nature of competency-based learning pushed me to work on these skills, which have prepared me tremendously for my post-secondary education. Even though many colleges are very test-driven and data-oriented, that doesn’t mean that the skill sets mentioned in Kettle Moraine’s graduate profile, and other skills created through competency-based learning, aren’t valuable during and after post-secondary education. Despite UW-Madison’s semi-traditional model of education and my upsetting 67% from freshman year, I have earned myself a spot on the Dean’s list every semester since and am involved with many extracurriculars and groups on campus. These skills have helped me navigate many different areas of my post-secondary career and will continue to help me throughout the rest of my life. I am the student I am today because of my competency-based learning experience, and I am excited to see where CBE takes other students in the future as well.

Briana Medina joined the Aurora Institute in May 2023 as a CompetencyWorks intern. She is a junior at the University of Wisconsin-Madison studying Political Science and Education Studies. She is committed to educational equity and is passionate about its relation to competency-based learning.

She currently serves on the UW-Madison College of Letters and Science Curriculum Committee, where she reviews and recommends course and program additions, revisions, and policies relating to academic offerings. In the past, Briana has worked as an intern at Kettle Moraine School for Arts and Performance, giving tours and teaching in a competency-based learning environment. Additionally, she worked with the Institute for Personalized Learning on panel discussions, high-level presentations, and blog posts.