How Do We Know Where Students Are?

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the thirteenth post in the blog series on the report, Quality and Equity by Design: Charting the Course for the Next Phase of Competency-Based Education.

To meet students where they are, districts and schools need to create the culture, the structure, and build a shared pedagogical philosophy that will enable much stronger relationships and much greater responsiveness than the traditional K-12 education system was designed. Before meeting students where they are, we must first understand where students are academically, emotionally, developmentally, and experientially.

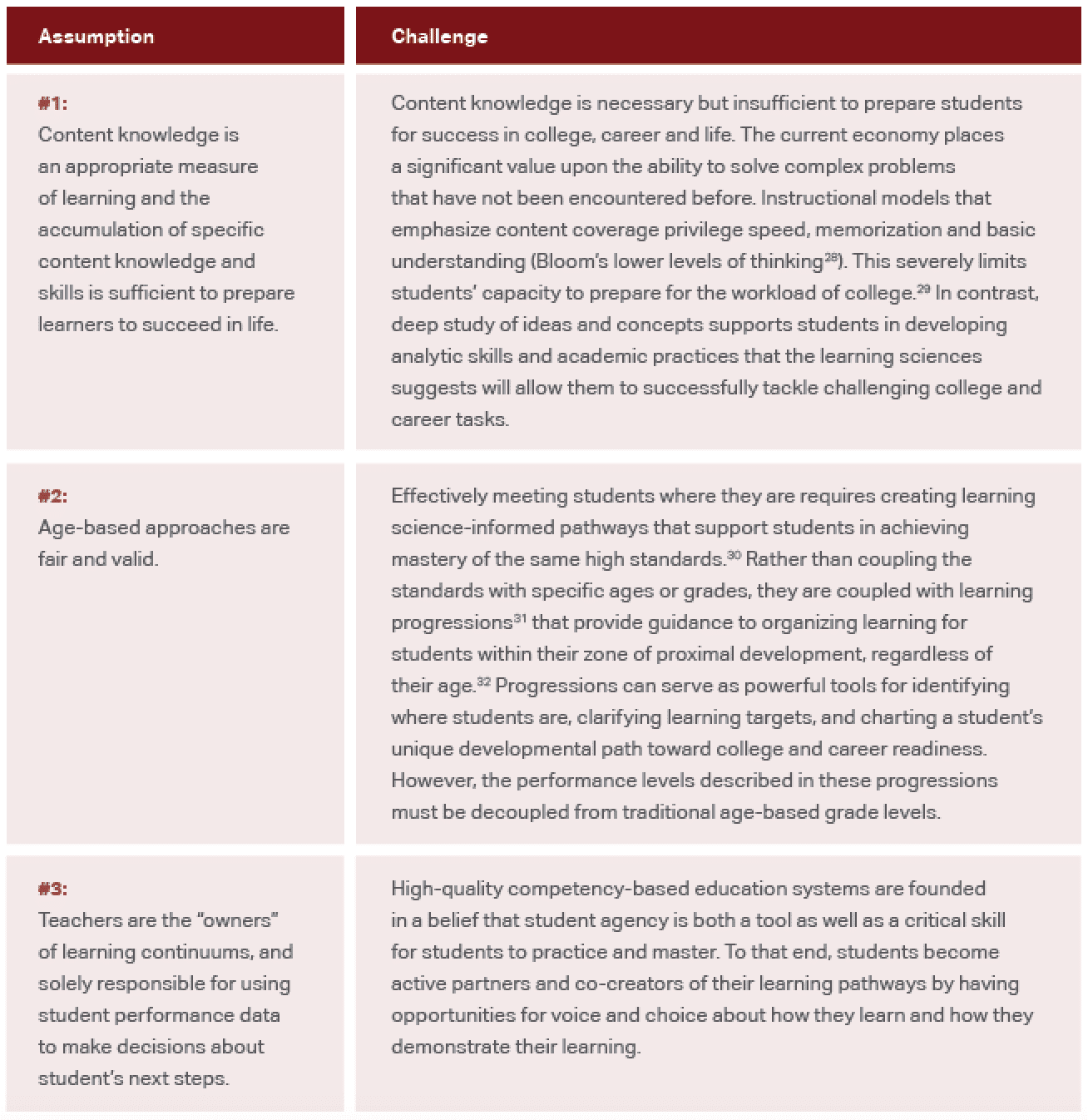

Understanding where students are requires honesty and objectivity. With that in mind, let’s start first by challenging some key assumptions within the current traditional system:

Next, a range of structural, pedagogical and relational shifts that are essential to identifying where students are in a learner-centered, equity-oriented model are described. These shifts are organized around three domains:

- First, internalizing and enacting a strengths-based, culturally responsive, inclusive and relationship-centered approach to knowing and caring for our students;

- Second, creating the equity-oriented structures that enable educators to know students and where they are; and

- Third, implementing a set of key practices that enable teachers-as-researchers to generate a rich, actionable stream of data to help them engage their students in identifying where they are and how to advance their learning.

Domain 1: Internalizing and enacting a strengths-based, culturally responsive, inclusive and relationship-centered approach to knowing and caring for our students.

Our goals for learners in a high-quality competency-based system go beyond the acquisition and ability to apply knowledge and skills to include self-efficacy and agency; as a result we must attend to knowing who are our students, in terms of both cognitive and non-cognitive circumstances. Knowing our students requires us to acknowledge and understand that students exist in dynamic contexts that mediate their lives and daily experiences, both inside out and outside of school. At the heart of an effective learner relationship is the primacy of a strengths-based approach to cultural competence, cultural relevance, and “funds of knowledge” in relation to working with communities. While cultural, social and economic challenges are real, and cast long shadows on our lives, the strength of communities and the strengths of individual students must sit at the heart of our thinking with regard to competency-based models and pedagogical practice. Creating an equitable, competency-based learning environment for all students requires adults to:

- Deepen our awareness and understanding of the impacts, for example, of culture, privilege, race and racial stress, as well as poverty and immigration, as they are experienced by learners and adults. Knowing our students means working to deepen our awareness of these complex factors — first in our own lives and also in the lives of our students — and constructing learning experiences and communities that meet students where they are, at the intersection of their complex identities and contexts.

- Cultivate relationships with students that are characterized by an “ethic of care.” This moves the work of identifying where students are beyond a purely diagnostic practice so that we also notice, acknowledge and respond positively to students’ feelings and desires.

Domain 2: Creating equity-oriented structures that enable educators to know students and where they are.

Structures in a high-quality competency-based system create the conditions for deep, purposeful and preparatory learning that is accessible to all learners. The four structural shifts discussed below are systems-level changes, although many schools operating with autonomy may be positioned to enact some or all of these changes.

- Hone indicators and measures for student learning to shift from credit acquisition to depth of knowledge, skills and dispositions. This means distilling our academic goals to a set of essential academic and lifelong learning competencies (in many schools and districts, these are coupled with developmental benchmarks or competencies to track physical and emotional development, particularly in younger children). Each competency is accompanied by a student-facing learning continuum that articulates what proficiency looks like at each performance level on the path to mastery. These skill-based progressions or continua become central tools to support instruction, inform student feedback, guide student self-monitoring, and help identify when students are ready to advance to the next level.

- Move from cohort-based grade levels to individual real-time progression through cognitive and non-cognitive mastery levels. Schools all over the world have implemented these “stage, not age” approaches. By contrast, competency-based systems in the the United States typically push up against policy that assumes age-based groupings. Despite this push, there are schools in the United States that have adopted this “stage, not age” approach. In some schools, this takes the form of multi-age “performance bands” (multiple years within which students can become competent in identified content and skills) as a way to organize capacity to meet students where they are.

- Personalize student pathways, reflecting an understanding of each student as an individual including their unique needs, assets and aspirations to inform selection, sequence and pace of learning. This is not an attempt to “lower” standards or track students, but rather to acknowledge that learners enter classrooms with a range of skills, and that learning itself is not a linear process. A personalized pathway accommodates and appropriately supports the “jaggedness” of each learner, while holding the end goals fixed.

- Strengthen structures currently in place that undermine strong relationship-building between learners and adults. In most traditional elementary schools, students are able to develop relationships with their teacher only to move classrooms and teachers each year. In high schools, sustained relationships are often only supported through a “homeroom” or advisory model (though even the composition of these groups can be changed year to year). These structures may cut short the time needed to deepen relationships. At Noble High School, a human capital strategy is purposefully designed to support long-term relationship building as part of their academic model. Specifically, interdisciplinary teaching teams stay with the same student cohort throughout their entire high school experience, a structure that they have designed to optimize their ability to provide timely, differentiated supports to all students.

Domain 3: Implementing a set of key instructional practices that enable teachers-as-researchers to generate a rich, actionable stream of data to help them engage their students about where they are and how to advance their learning.

Once we know our students and where they are, acting upon that information requires teachers to become action researchers and facilitators for learning. Practitioner research involves constantly posing questions about who are our students, where are they, what strengths can we build upon, and how to most effectively identify and respond to the next step in their learning. On a daily basis, educators in learner-centered classrooms put into practice the following pedagogical strategies designed to help identify where students are:

- Assessment is treated as a learning experience: an opportunity to take stock of what one has learned, synthesize ideas and apply them to new contexts. Formative assessments are available in daily, moment-by-moment occurrences: conferences, peer feedback, observations, and self-reporting cues, as well as oral or written forms. These embedded opportunities are often coupled with more formal formative assessment opportunities that provide students with additional learning moments and provide both teachers and students with critical data about student understanding.

- Student discourse offers a rich, often overlooked, stream of data for diagnosing student needs and gauging understanding in real time. The more teachers can observe students as they make meaning of new information, draw connections to their existing schema, and identify gaps or misconceptions, the more promptly teachers can seize the opportunity for providing responsive, tailored supports. Expanding productive student talk also reduces barriers that struggling writers often face when asked to provide written responses to show their thinking or ability to synthesize ideas.

- Students co-own the process of identifying where they are and in shaping the path ahead, and practice student agency in their own learning journey. Students should have the opportunity to access and interpret their data in real time, participate fully in the planning and decision-making process for their learning pathway, and be encouraged to reflect on past decisions and outcomes. This participation allows students to further their learning and use metacognition to inform future decisions.

- Educators create ongoing metacognitive and reflective experiences for learners in order to position them as developing experts. As John Dewey reminds us, “We do not learn from experience. We learn from reflecting on experience.” One of the critical tools that supports students in becoming independent, self-regulating learners is the development of metacognitive skills: the capacity to monitor their learning, identify the limits of their knowledge or ability, and identify and use strategies and tools to expand their capacity. This is one of the critical distinctions between novice and expert learners. The stronger students’ metacognitive skills are, the stronger their capacity to “know where they are” without depending on teachers or others for this information. These pedagogical shifts begin the work of creating learning spaces in which both teachers and students know “where they are” and can make informed decisions about how to move forward.

- The label “failing students” is replaced with terms that describe students’ progress and skills (rather than their character). Students’ skills and knowledge are described as “emerging,” “proficient,” “college-ready,” etc. as reference points for where students are. In a true competency-based system, students cannot fail.

Follow this blog series for more articles charting the course for the next phase of competency-based education, or download the full report:

- Quality and Equity by Design

- Readiness for College, Career and Life: The Purpose of K-12 Public Education Today

- Why A Competency-Based System Is Needed: 10 Ways the Traditional System Contributes to Inequity

- How Competency-Based Education Differs from the Traditional System of Education

- Competency-Based Education and Personalized Learning Go Hand-In-Hand

- Building Shared Understanding of Quality through Design Principles

- 5 Quality Design Principles for Culture

- 7 Quality Design Principles for Structure

- 4 Quality Design Principles for Teaching and Learning

- Designing a Competency-Based System for Equity

- An Equity Framework for Competency-Based Education

- Meeting Students Where They Are So That Everyone Masters Learning

Learn more:

- Meeting Students Where They Are

- Readings on the Development of Children (2nd ed.)

- What Does It Mean to Meet Students Where They Are?

- Researchers Find That Frequent Tests Can Boost Learning (Scientific American)

- The Role of Advisory in Personalizing the Secondary Experience (Getting Smart)

- How does ‘toxic stress’ of poverty hurt the developing brain? (PBS News Hour)

- Adolescent Trust in Teachers: Implications for Behavior in the High School Classroom (National Association of School Psychologists)

- Funds of Knowledge for Teaching: Using a Qualitative Approach to Connect Homes and Classrooms (JSTOR)