How Do You Measure Competency? Curriculum Can Help Guide the Way

CompetencyWorks Blog

Competency-based education is not about reformation – it is about transformation. Old processes and models of teaching and learning do not get at the intrinsic value of teaching and learning with a targeted focus on standards and mastery. If how we teach must change, then how we plan for instruction must change, too.

Competency-based education is not about reformation – it is about transformation. Old processes and models of teaching and learning do not get at the intrinsic value of teaching and learning with a targeted focus on standards and mastery. If how we teach must change, then how we plan for instruction must change, too.

Curriculum can no longer focus solely on content – it must shift to encompass skills. But which skills? What will enable students to attain high standards and expectations? Currently, the most efficient way to understand which skills will result in higher levels of achievement comes from the process of unpacking standards.

Ainsworth (and Reeves before him) realized that no teacher – and certainly no student – can expect mastery of more than fifty educational standards (in English/Language Arts alone) in one school year. When our district piloted a curriculum that encompassed all ELA standards in the Common Core for tenth grade, we found that each standard could only be directly addressed about four or five times a year. No one can master the ability to identify a theme and track its development over the course of a text by practicing it four times a year for about forty minutes per session (CCSS ELA standard RL9-10.1). Not only did we ignore the research regarding how the brain learns (Sousa 2011), we also ignored the interconnectivity of ideas and concepts and its power in acquiring new knowledge and skills (Demarest 2010).

Our efforts defied the heart of competency-based education – adaptable pacing, multiple and flexible pathways, reflection and practice, and differentiation that is personalized. It became very clear that the old ways of creating a curriculum could not communicate the tenets of this educational belief system. In fact, the good intentions behind the curriculum development talked a good game – “all students can learn at high levels” – but then it forced both teachers and students to move at a pre-determined pace and measure progress at pre-determined intervals. Our curriculum was communicating that all students who could keep up could learn at high levels. Some schools interpreted curricular imperatives even more narrowly – teachers of the same subject and level should be teaching the same thing on the same day in the same way. So in addition to keeping up, students who needed alternative modalities were out of luck.

Designing curriculum in a competency-based system means exploring flexibility as well as accountability. Unpacking the standards is an activity that communicates two important ideas about competency-based education.

First, if our focus is on the standards, then our concern should center on the skills students need to attain those standards.

Second, if we want all students to find success, then we have to allow time, opportunity, and a variety of methods for students to demonstrate those skills.

Curriculum development needs to encompass this philosophy, and it can do this most effectively when the developers have a philosophy of curriculum aligned with the district’s mission and vision, and the development plan encompasses a clear focus on skills that promote attainment of standards through competency-based assessment and practice.

Effective Curriculum Development

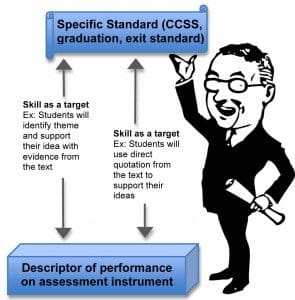

In a competency-based environment for teaching, learning, and assessment, the focus is on the skills students need to attain state-adopted standards. For most of us, those standards are the Common Core State Standards. For most of us, we design learning targets to address the standards, but that can be the problem with curriculum and competency-based systems: the standards aren’t necessarily the targets. They are the goals we seek to attain. Instead, the targets address the skills that students need to master in order to reach competency in the standards.

Think of it this way: your school could have graduation standards or competencies that were written to encompass and address the learning outcomes expressed in the Common Core State Standards. How will students attain those competencies? And when will you know they have attained them?

Curriculum needs to address that issue, no matter the grade level. In order for a student to successfully complete first grade, what competencies (or standards) should be mastered? How about when that first grader graduates from elementary school? What competencies should be mastered?

The first structures in competency-based models, then, are those explicit exit standards, defined at specific intervals in a child’s education – especially graduation. Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium has created “claims” that guide their assessment practices. These “claims” reflect and measure – according to SBAC – the Common Core State Standards.

The targets, therefore, are not the standards themselves, but the actual skills necessary to achieve that standard. These targets are what define coursework, assessment practices, and student achievement progress.

They also should define what and how you assess student progress toward a standard or competency.

Interconnectivity: Curriculum and Assessment

Teachers, then, look to the curriculum to help guide them toward Common Core State Standards that require their focus and attention. The only way curriculum can accurately diagnose these needs is through aligned assessment. In a competency-based system, assessment and curriculum must work coherently. It is also critical that assessment instruments – rubrics, for example – be descriptors of performance (Brookhart 2013). Students’ performance, then, would be the skills they will use to demonstrate their competency with standards.

Curriculum for a competency-based educational system must be linked closely and strategically with assessment that is designed to develop skills that will ultimately be the tools students use when working with standards. How that curriculum is developed is wide open to those who would create it. Ainsworth’s model of rigorous curriculum design (2010) lends itself nicely to a competency-based model, but others (i.e., Jacobs 2010, Erickson 2001) can work as well and efficiently for students.

What is more critical than the curriculum model is the curriculum itself: an inquiry model (Kuhlthau, Caspari & Maniotes 2007), for example, allows students opportunities to explore information and develop their own strategies for how it is interrelated to their personalized avenues of study. For example, instead of a high school English unit on the Steinbeck novel Of Mice and Men, a unit could begin with an exploration of the American Dream, or poverty in America. Students could have voice and choice, selecting from a variety of books that document how poverty has influences migration across the nation: from The Grapes of Wrath to House on Mango Street, Maus, or the nonfiction Nickel and Dimed. Students are researching, engaging in meaningful dialogue about an issue or theme rather than a book. Students can present their findings and their research – and cover more Common Core standards in a few weeks than a teacher could reasonably address if she targeted them systematically and individually. The model here also encourages deep exploration and the use of sophisticated, developing skills that will only become more developed and precise through authentic use.

John Dewey, nearly 100 years ago, observed that education should not be preparation for life: education should be life itself. Competency-based learning exemplifies Dewey’s philosophy through its emphasis on student voice and choice, authentic learning experiences, and personalization that focuses on student success. Curriculum is a guide and a tool – it embraces standards and promotes skills needed to achieve them. But without quality assessment instruments, the best curriculum may never be fully lived or realized by teachers and students.

If education should be life itself, so should curriculum. Its assessments, as well as the philosophy and values that helped shape it, can be truly transformative for students.

References

Ainsworth, L. (2010). Rigorous curriculum design: How to create curricular units of study that align standards, instruction, and assessment. Englewood, CO: Lead Learn Press.

Ainsworth, L. (2013). Prioritizing the common core: Identifying specific standards to emphasize the most. Englewood, CO: Lead Learn Press.

Demarest, E. J. (2010). A learning-centered framework for education reform: What does it mean for national policy? New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Erickson, H. L. (2001). Stirring the head, heart, and soul: Redefining curriculum and instruction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Jacobs, H. H. (2010). Curriculum 21: Essential Education for a Changing World. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Kuhlthau, C. C., Caspari, A. K., & Maniotes, L. K. (2007). Guided inquiry: Learning in the 21st century. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Reeves, D. B. (1997). Making standards work: How to implement standards-based assessments in the classroom, school, and district. Denver, CO: Advanced Learning Centers.

Sousa, D. A. (2006). How the brain learns. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Caroline Gordon Messenger has taught English for grades 6 through 12 for the past 14 years. Before earning her teacher certification, she was a professional journalist. Messenger holds a Master of Arts in Oral Traditions and a research Master of Philosophy in the Sociology of Education from Lancaster University in Lancaster, U.K. She currently teaches English and Journalism at Naugatuck High School in Naugatuck, CT. Reach her on Twitter: @cjmessenger