In Real Life: How Do We Know If Competency-Based Education Is Working?

CompetencyWorks Blog

This article is the eighth in a nine-part “In Real Life” series based on the complex, fundamental questions that practitioners in competency-based systems grapple with “in real life.” Links to the other posts can be found at the end of this article.

This article is the eighth in a nine-part “In Real Life” series based on the complex, fundamental questions that practitioners in competency-based systems grapple with “in real life.” Links to the other posts can be found at the end of this article.

Competency-based education (CBE) systems across the country share one ambitious goal: to have every child master the knowledge and skills essential for success in college and career. It is a bold North Star because it means every child and every essential competency.

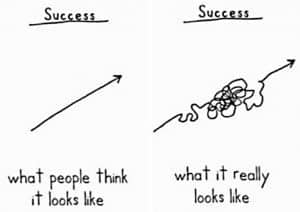

To succeed, CBE schools and districts must be able to determine how well their systems’ practices and structures are contributing toward this goal. Through the use of quality frameworks such as CompetencyWorks’ Quality Principles for Competency-Based Education and processes for ongoing continuous improvement and organizational learning, leaders of CBE systems can track progress and make adjustments to their systems in real time. After all, success doesn’t happen overnight. Instead, it looks more like the famed napkin drawing (above) attributed to comedian Demetri Martin: convoluted and full of setbacks and redirection. CBE systems must be able to determine when and how to make adjustments.

What can we learn from “real life” CBE leaders about monitoring the success of their systems and making adjustments when necessary? Three related pieces of advice emerged across the stories shared by the practitioners interviewed for this series:

- Collect and analyze multiple types of data throughout the year;

- Ensure reliability and consistency across the system; and

- Prioritize educator collaboration.

Robust Data Systems and Practices

The kinds of performance data that are typically collected by districts – such as achievement on standardized assessments, graduation rates, and dropout rates – are useful in benchmarking progress against expectations, typically at yearly intervals. However, continuous improvement requires additional data sets that are more nuanced and frequent in order to illuminate what’s working, what might need to change, and how.

Seeking greater nuance, many CBE systems survey stakeholders in order to understand how well their systems are working from diverse perspectives. For example, the Revere Public Schools in Massachusetts implemented a system of student, parent, and teacher surveys that are used to reflect on the school district’s High School Logic Model and identify areas for improvement. Similarly, Casco Bay High School in Maine launched a Student Data Task Force to conduct an informal data audit. They surveyed students and parent advocate groups and examined the data for any demographic patterns in which students drop out, are in student leadership roles, are in summer school, are making regular use of remedial structures, and so on. In addition to this evidence, they looked at patterns in quantitative data including suspensions and how many (and which) students are not meeting standards at the end of each trimester. Identified trends then became the subject of whole-faculty professional development.

Continuous improvement of the Linked Learning schools in the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) is supported by field visits by district staff and coaches conducted three times per year per site. The external observers visit classrooms, examine student work, talk with students, consult school staff, and evaluate what they find against Linked Learning implementation benchmarks. Each visit includes a consultancy with school staff to discuss areas and ways in which implementation can be strengthened.

Mechanisms to ensure consistency and reliability

If every child is to reach mastery, CBE systems must be able to ensure that the rigor of student learning experiences and expectations is consistent across the system. Without mechanisms to ensure consistency and reliability, students could be misled to think they are “proficient” or “competent” when in fact they have been held to a lower bar. Conversely, some students’ opportunity to reach proficiency could be compromised because they were not afforded the rich learning experiences of their peers in other parts of the system.

Last year, the Linked Learning schools in LAUSD took steps to ensure that the project-based learning (PBL) assignments across its schools were consistently high-quality by collecting and reviewing the rigor of over 120 PBL assignments (which they call “PBLs” for short). According to Esther Soliman, LAUSD’s administrator for Linked Learning, CTE, and Work Experience, the schools that had previously reached the highest level of certification in the Linked Learning program “have been practicing this for a while and had PBLs that were rich and exciting, the result of years of development and honing. For others, the rigor wasn’t quite there.” In response, schools are now focusing professional development on refining the PBLs in areas identified for improvement.

For Alison Kearney, Assistant Principal at Noble High School in Maine, cross-school calibration is an important means of ensuring equity. “We have a ‘school-within-a-school’ model with two distinct academies and two semi-autonomous groups of teachers. Teachers in either academy may be doing great things, but there had been no consistency with what was happening in the other academy.” To remedy this, Noble High School implemented common assessments. Teachers teaching the same subject across the academies now offer at least one common validated assessment per graduation standard. “This way it doesn’t matter which teacher a student gets,” says Kearney; “the system is more equitable.”

Teacher Collaboration

When it comes to ensuring quality, “one thing that’s been crucial is making sure that teachers have collaborative time,” says Dianne Kelly, Superintendent of Revere Public Schools in Massachusetts. “In the new contracts for our elementary and middle school teachers, we were able to ensure at least 40 minutes of collaborative time every day. We are still working this out for high school, but we know that teachers need to meet more than once a week to enable deep discussions around how to get this work done.”

Deep discussions among teachers are central to improving instruction. At Casco Bay High School, professional learning communities of teachers choose two students representing two different kinds of learner profiles to serve as “case studies” for improving their practice. Over the course of a year, teachers pair up and meet monthly to analyze samples of these students’ work and to collaboratively determine next steps to help the students meet or exceed standards. Casco Bay teachers also meet together for peer-to-peer curriculum reviews twice per year.

At Noble High School, teachers meet across grade-level partners to collaboratively score their large common summative assessments. They also routinely engage in data-driven dialogue exercises to examine their grading practices and determine whether grading is equitable across teachers.

As Kearney notes, “there are so many variables that can contribute to student outcomes, so it can be challenging to isolate what might be contributing to any success we’re having. We are continuing to look at how we know whether our system is working.” Like other CBE schools and districts, they collaborate to revise their processes according to what they find.

—

Read the rest of the “In Real Life” series at the following links:

- Series Introduction

- Part 1: Who Gets to Decide Which Student Outcomes Matter?

- Part 2: Designing Outcomes Aimed for Equity

- Part 3: How can CBE systems ensure learning is deep, ongoing, and integrated?

- Part 4: How feedback loops and student supports help ensure learning is deep, ongoing, and integrated.

- Part 5: How do CBE systems manage differences in pace?

- Part 6: How do CBE systems support all students to reach mastery?

—

Jennifer Poon’s mission is to effect social justice by modernizing the public education system to be more responsive to the needs of all learners, especially those most historically underserved. Currently, she is consulting on projects of interest while serving as a Fellow with the Center for Innovation in Education. Previously, Jennifer directed the Innovation Lab Network at the Council of Chief State School Officers. Prior to that, she taught at King/Drew High School in Compton, CA. Tweet to her @JDPoon.