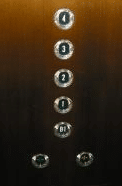

Next Stop, Level 4

CompetencyWorks Blog

Depending on which knowledge taxonomy you use, the highest level with the deepest learning is either Level 4 or Level 6. As we think about equity in a personalized, competency-based world, how do we ensure that all students – even those who entered school at an earlier point on the learning progression than their peers and are on a steeper trajectory – have the chance to deeply engage in learning? How do we make sure that students who want extra challenges but want to stay with their peers can continue to grow without advancing to the next level of studies?

Depending on which knowledge taxonomy you use, the highest level with the deepest learning is either Level 4 or Level 6. As we think about equity in a personalized, competency-based world, how do we ensure that all students – even those who entered school at an earlier point on the learning progression than their peers and are on a steeper trajectory – have the chance to deeply engage in learning? How do we make sure that students who want extra challenges but want to stay with their peers can continue to grow without advancing to the next level of studies?

The granularity of standards may be too fine to have students trying to do Level 4 for each one. Learning progressions organized around anchor (power) standards and essential understandings will lend themselves more easily to knowledge utilization. Still, we know that incorporating projects, designed by teachers, students or together, takes time, planning, resources and flexibility. So how are schools managing to create Level 4 opportunities and ensuring that all students have a chance to dive deep into their learning?

Schools are using a variety of techniques:

Periodic Projects: Boston Day and Evening Academy has a Project Month with a culminating symposium night during which students present their projects. Students choose among projects designed by teachers with the goal of applying what they have been learning and building their deeper learning (habits or 21st century) skills. In 2013, the projects included Darkroom Chemistry (Pinhole Photography); Rocketry; Psychology: Secrets of the Human Mind; Exploring Conflict Through Film; America Through the Eyes of a Street Artist; Swimming First Aid/CPR; Actors’ Shakespeare Project; and Less is More–a study of sustainable architecture

Casco Bay High School in Portland, Maine offers Intensives two times during the school year in which students study one topic for a number of days. According to Making Mastery Work, “Intensive topics range from Bridge-Building Engineering to Winter Sports.” However, it’s important to note, students that haven’t mastered all their work use this time to continue to work on specific standards. It’s certainly an incentive to keep pace, as students can lose out on the fun of the intensives.

Expanded Learning Opportunities (ELO): Pittsfield Middle and High School offers students ELOs for credit. New Hampshire state policy allows this, but not every district takes advantage of it. At PMHS, ELOs are personalized around students’ development, interests, and academic needs. For some, it is focused more on career development, for others, on a way to develop their skills and personal interests, and for others, a means to pursue advanced learning. The competencies/standards are used, including ELA writing standards, to design the ELOs. ELOs are not required, but available to struggling and high-achieving students alike.

Course Projects: Diploma Plus schools, such as APEX in California, serve students that are over-age and under-credited. The schools are very personalized because students enter with a range of skills and gaps in knowledge. Diploma Plus explicitly uses Bloom’s Taxonomy to manage depth of knowledge so students know what level they are working at. Each course expects students to participate in a project so that they have a chance to make connections within the course, to other courses and/or to their lives.

Honors Projects: Sanborn Regional High School in New Hampshire began thinking differently about honors. Instead of honors courses, the school began to focus on honors work. As described by Ellen Hume-Howard and Brian Stack, “ Instead of offering separate honors sections, we allowed students to contract for honors within their existing class. With each honors contract, teachers and students came to an agreement over what their learning plan would look like, how their work would differ from a student who was not contracting for honors credit, and how the teacher would be assessing their work. This shifted our thinking of honors, from a definition of where they learn to an articulation of what they produce.”

Post-Level 3: In some schools I’ve visited, once students demonstrated Level 3, they had the choice to move onto the next unit, work on other studies, or pursue Level 4. In some cases, teachers had developed Level 4 projects for students, in others students designed their own in consultation with their teacher. In some cases, this did open the door to Level 4, and in other cases it looked more like extra credit. One of the challenges in this approach is trying to determine when students delve into Level 4 – at the level of larger competencies or after reaching Level 3 at each granular standard or, in the language of many districts, “measurable topic” or “learning target.”

Project-based Learning: Schools that emphasize project-based learning organize their schedules and resources around Level 4 and back into standards. ACE Leadership, New Tech, and all the other schools start with project- and problem-based learning as the core instructional approach. Students build up their love of learning, their understanding of their learning process, and all those great deeper learning skills. The challenge, however, is how to make sure that students also build up all those foundational skills and content needed for knowledge utilization. Repeatedly I hear that when students enter without pre-requisite knowledge and skills, there isn’t enough time to do both so the priority is the deeper learning skills that will serve students well throughout life. However, I wonder – could blended learning and adaptive software help students build up their skills at Level 1 and 2?

Chris Sturgis is Principal of MetisNet, a consulting firm that specializes in supporting foundations and special initiatives in strategy development, coaching and rapid research. She is strategic advisor to the Youth Transition Funders Group and manages the Connected by 25 blog.