Pace Yourself: Restructuring Content In A Competency-Based Classroom

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post was first published by Blend My Learning on July 30, 2013. It has been reposted here with permission.

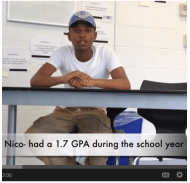

Nico scrunched up his face. He was working on standard twenty: solving free-fall problems. Math is tricky for him, so I anticipated that he might have questions. He sighed, put his pen down and asked me, “Mr. D., why did you become a teacher?” I did a small double-take, blinked a few times, and said I could give him the short answer now and the long answer after class.

“The short answer, Nico, is that our country is a place where certain people’s voices aren’t heard enough, and I thought that education might do something about that.” Nico smiled and turned back to finishing his calculations; about fifteen minutes later he had mastered the lab and the quiz for that standard. After class, he and I spoke about the George Zimmerman trial and what it meant to him as a black boy in DC. It was a fascinating conversation that I wish I had recorded.

I include this exchange because I have come to realize that one advantage of my summer pilot is that ninety-five percent of my interactions with students these past three weeks have been productive and directly related to learning. There have been only three occasions in the past forty-five hours in my classroom where a student was doing something that was distracting enough to a peer that I had to address it. This is not because I built phenomenal classroom culture in three weeks; it is because a competency-based curriculum values mastery over time. I don’t feel that terror that all teachers feel when a student misbehaves in a traditional classroom, that fear that if we don’t all get through this material, right now, we’re going to lose time. I don’t feel the need to have eleven arms dragging each of my eleven students through the same content at the same time for fear that they will drown. Instead of talking about how students are or aren’t “using their time well,” I get to discuss with them what they do or don’t understand right now.

I know that my curriculum needs more work, particularly with regard to differentiation, and that I need to do a better job explicitly teaching students how to be independent learners (three weeks is not enough for this metacognitive skill development when I have thirty-three physics standards and twelve labs to pack in on top). I do know, though, that I was able to talk to Nico about my motivation for being a teacher for two minutes in the middle of class. No one else had to stop and wait for us.

Nico is ahead of the pacing guide for the course and earned time to use at his discretion, and every other student was occupied in a relevant, though far from perfect, learning experience related to their personal level of progress in the course. I felt tremendous honor that Nico wanted to use his discretionary time to ask me that personal question, and lucky for me, I had the freedom to answer it in a way that may have enhanced his learning and deepened our relationship.

In great classrooms, one hundred percent of teacher-student interactions are invaluable to furthering the learning of students. Maybe one way to shift the needle in that direction is to re-imagine how we structure our classrooms. Let’s remove that time-bound stress from teachers so that they only have to think about learning. Doing so has helped me feel like I have the time to talk about what actually matters.