Performance-Based Learning in a Dual Immersion School

CompetencyWorks Blog

This article is the twelfth in the Designing Performance-Based Learning at D51 series. A reminder: D51 uses the phrase performance-based learning or P-BL.

This article is the twelfth in the Designing Performance-Based Learning at D51 series. A reminder: D51 uses the phrase performance-based learning or P-BL.

The Dual Immersion Academy (DIA) is not one of D51’s performance-based learning demonstration schools – it’s one of the schools that is going forward and building the effective practices because it simply can’t wait. Bil Pfaffendorf, a professional learning facilitator, and I made a quick stop to learn about how the efforts in building the effective practices were going. I am so glad I did, as I realized that the deep conversations about teaching and learning are rippling throughout the district – not just in the demonstration schools.

Principal Monica Heptner outlined the structure of the school: Of the 285 students K-5 that DIA serves, approximately 50 percent are English Language Learners and the other half are there to learn Spanish. Language is an intentional set of skills developed at DIA, with students building their skills in both languages. There are two language progressions, and students are tracked on both. Students come to school with different levels of familiarity with each of the languages. Students receive literacy in both languages, with math and reading in English and science and social sciences in Spanish.

Heptner provided examples of their progress in incorporating the effective practices, some of which had been previously used in the school to some degree:

- DIA has started the process of learning the fundamental skills for performance-based learning. Last year, the teachers focused on integrating Habits of Mind into their work. This year, they are focusing on growth mindset with an enhancement – they want students to be thinking about what it means to have a mathematical mindset.

- The workshop model allows the teacher or instructional assistant to pull a few students to work with more closely. The other students work at the tables with the assumption that they will help each out, both in language development and the task at hand. They’ve learned that everything works more smoothly if teachers make sure that every table has a “leader” – not an appointed leader, but one who fully understands the task and can guide other students.

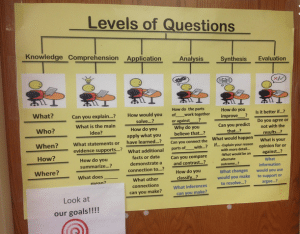

In the fifth year, students begin to use Thinking Maps and learn how to ask quality questions. They learn about Bloom’s taxonomy to help them understand the depth of knowledge of the questions. Heptner noted, “One of the most important things is to make sure that students are learning the academic language and how to use it in academic conversation.” DIA uses strategies from La Cosecha to build academic conversation in both languages.

In the fifth year, students begin to use Thinking Maps and learn how to ask quality questions. They learn about Bloom’s taxonomy to help them understand the depth of knowledge of the questions. Heptner noted, “One of the most important things is to make sure that students are learning the academic language and how to use it in academic conversation.” DIA uses strategies from La Cosecha to build academic conversation in both languages.

- Opportunity to apply skills to real-life problems is important. Last year, students examined water distribution of the Colorado River, which cuts through Grand Junction. After mapping the river and looking at distribution and implications for Mexico, the students presented a redistribution plan to the mayor.

- Teachers at DIA are able to select from the menu of Design Labs on the specific skills they want to develop. Gallery walks have become a very helpful tool for cross-fertilizing ideas and spreading effective techniques. Heptner explained, “We are always helpful, asking teachers “What do you notice?” to be able to draw out awareness of practices and what it means to implement them effectively. Our teachers are becoming more intentional.”

She commented that the school is becoming better at “failing forward” so that students are able to learn from errors and mistakes. In language development, this includes “hearing forward,” as students are exposed to more and learn to use vocabulary in both languages. Mistakes are common, so the environment is bubbling over with learning.

Our conversation turned to growth as Heptner explained DIA’s practice of data digs: After each twenty-one-day cycle, teachers look closely at how students are doing. Heptner explained that this process is increasing inter-rater reliability as teachers look at student work during this process. Bil emphasized that in a fully developed performance-based system, it is important to have continuous improvement processes like the data digs to ensure every student is demonstrating growth as well as processes that help the school look at its performance. He emphasized, “The only way you can tell if you are going in the right direction is to monitor student growth and respond immediately when there is a suggestion that there is a problem.”

Our conversation also turned to the question about making sure students fully understand the core concepts that undergird the foundational skills in literacy and math. For example, in kindergarten, drawing is the beginning of writing. Children learn about symbols, which will help them understand the power of letters (and numbers) later on. They can begin to think about the flow of a story by creating storyboards for the beginning, middle, and end. Heptner mentioned that one of her concerns is that students have to have enough exposure to a set of concepts and skills to get to mastery. Doing something once, even if students do it correctly, isn’t enough. Given that children develop differently during childhood (and in adolescence, for that matter) it is important that students who need more opportunity to explore the fundamental concepts do so until the concepts are fully ingrained in their understanding.

Bil noted that math requires vigilance in ensuring students are mastering earlier steps, as these become prerequisites for more advanced learning. “The math learning progressions are highly interdependent,” he said. “Students need to deeply understand the early concepts, otherwise they are simply memorizing procedures later on.” Heptner added, “We are locked into a traditional way of teaching math. As we think about the communities of our students, we want to be open to differences in how language and culture shape learning.” (Recently, I listened to a Students at the Center webinar with Rochelle Gutierrez that opened my eyes to how narrow our approach to mathematics is.) One of the ways they weave the language learning component in mathematics is by having students defend in English the answer to the word problems, a good practice for any school. DIA is using Advantaged Math Recovery to help support students who need more opportunity to practice and reinforce mathematical concepts.

Heptner raised an important insight about what it means to have more student ownership in learning when they are learning both another language and other academic domains. “Our teachers think about two types of scaffolding,” she said. “One is for language and one is for content, with rubrics in both languages. Students need to have a strong set of Habits of Mind to make sense of the scaffolding, especially meta-cognition. They need to be able to think, “Do I need help with the language or with the content in order to take advantage of the different scaffolds?’” Thus, students learning a language while also learning within the academic domains are going to have an even more refined set of metacognitive skills. If performance indicators included this capacity, it’s easy to say that our ELL and dual language students would outperform others.

Read the Entire Series:

Post #1 – Designing Performance-Based Learning at D51

Post #2 – Building Consensus for Change at D51

Post #3 – The Vision of Performance-Based Education at D51

Post #4 – Holacracy: Organizing for Change at D51

Post #5 – Growing into the Framework: D51’s Implementation Strategy

Post #6 – Laying the Foundation with Culture and Climate

Post #7 – Supporting Teachers at D51: A Conversation with the Professional Learning Facilitators

Post #8 – Creating a Transparent Performance-Based System at D51

Post # 9 – New Emerson: Learning the Effective Practices of the Learner-Centered Classroom

Post #10 – Transparency and Trust

Post #11 – Lincoln Orchard Mesa: What Did You Notice?