Redesigning the Syllabus to Reflect the Learning Journey

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post originally appeared at EdSurge on September 10, 2017.

Personalized learning is still in its infancy—as are the curricular tools and resources available to support teachers in implementing it.

Currently, there is no shortage of articles offering a high-level look at how and why personalized learning will impact student growth, and conference sessions where teachers are encouraged to change the way they teach, but not given the tools to modify their instructional practices. There are plenty of resources with step-by-step guides and blueprints designed to walk teachers through a process to personalize learning. Additionally, there is a growing number of online platforms and prepackaged curricular products (both free and at cost)—not to mention the new stamp on existing tools—you know, the sticker that says “personalize learning with (insert product name.)”

But, for personalized learning to be personal—it must be less formal and formulaic. We need to design student-centered learning experiences and that takes time, practice and support.

The Syllabus Gets a Facelift

If we think about learning as a journey that gets compartmentalized in formal education, then the first experience for middle and high school students is often the syllabus. In many ways, the traditional syllabus places restrictions on when, what and how students will learn. It sets expectations for how growth will be measured and what penalties will be enforced for late work or missing class. Most syllabi lack flexibility and aren’t very engaging; which contradicts everything we know about high quality teaching and learning.

I currently work at Allen Academy in Bryan, Texas, as the Head of Middle and Upper School and I teach one 8th grade geography class. Back in 2011, I was getting my feet wet with blended learning and experimenting with new pedagogical practices in my geography class. As a result of my recent transition to a blended learning environment and my desire to turn control of learning over to my students, I decided the traditional syllabus needed to be turned on its head.

Redesigning the Syllabus Starting With Student Experience

Conventional syllabi are developed from the perspective of the teacher—designed to present what he or she plans to include in a course. I wanted to develop an alternative version that looked through the lens of the student, and my vision was to tailor each one to reflect what a particular learner would be doing every step of the way throughout the course. This was not simply a more visually appealing version of a classic syllabus, it was a radical overhaul of the student experience with the primary goal of changing their perception of their role as a learner.

This drastic class redesign demanded that I ask myself some big questions: what content was required, what elements of learning could students control and what traditional and new measures I could use to gauge progress? Almost every question led to another. How much control could I give students over their modalities of learning, what would the challenges and successes of self-paced learning be, and if students had more control over how they demonstrated mastery, then what would rubrics look like?

Seven years ago, that first course redesign was a big shift for me. I had been teaching eighth grade geography for four years at that point, and historically, I had used a textbook and pacing chart to cover the curriculum. I used traditional grading practices, assessing student progress through quizzes, tests, project, midterms and finals each year. I was confident that students were learning and their grades supported that. There was little urgency for change—certainly not from my administration or peers. But I had this nagging feeling that my students deserved better. I knew they could make more progress if they had more flexibility to make decisions—but that couldn’t happen within the rigid structure that existed.

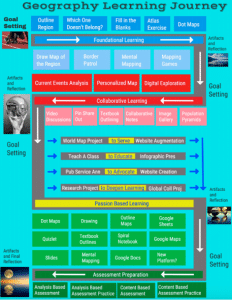

The heaviest lift for that first redesign was figuring out how to parcel out the course in a way that would give students more flexibility and choice. Abandoning traditional units and chapters and coming up with new potential segments of learning was a strenuous process. For that first one, I divided my class into three segments: Foundation, Content and Skills, and Assessment. I worked tirelessly to gather old and new resources, align them to each segment, and upload them to a website so that my students could access them at their own pace.

Once my course materials were online, I built out the learning experiences within those groupings and began to flesh them out—first on paper, and then using the program Piktochart, an infographic builder tool to design the visual.

In reflection, that initial redesign was a first step, but it needed to evolve. The course still put the teacher in the driver’s seat, but as I experimented, I learned that for this kind of learning experience to be effective, the student needs to drive it. There were some logistical barriers with the first design, primarily that it presented a limited view of assessment.Through an iterative process, it morphed into a more robust visual, with elements that broadened the scope of assessment options and focused more on learning and preparation for demonstrating growth. As I improved it, I also worked on developing a smoother flow and incorporating reflections into the course.

From 2011-2015, I continued to iterate on the course design for my class. Fueled by a combination of student feedback, parent input and new developments in education such as Carol Dweck’s Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, the learning journey was born.

Remember Life—the board game where you made decisions about going to college, stocks, insurance and having a family? I started thinking about how to transform our existing syllabus format to mimic elements of the game, specifically the idea of paths with choices. Giving students the opportunity to make decisions about what they learn, how they learn it and how they can demonstrate mastery seemed like a no brainer, so I began building a prototype. It has evolved over time, and now, along with me, some other teachers in our school refer to the revamped syllabi as “learning journeys.”

As part of another iteration, I started visually distinguishing required and optional activities, and embedded goal setting and reflections throughout. Perhaps the biggest change was that I replaced the content and skills portion with two new segments: collaborative learning and passion-based learning. Each of these changes put students at the center and supported them in their quest to make decisions.

I became the Head of Middle and Upper School at Allen Academy in 2015, and though I still taught one section of geography, I spent a good bit of my time leading workshops and supporting other teachers in curriculum development. That’s when the learning journey began to gain some traction.

How the Learning Journey Caught Fire

Seven years ago, I began developing my first learning journey, and today there are four other classes at our school using learning journeys to shape student experiences for the class.

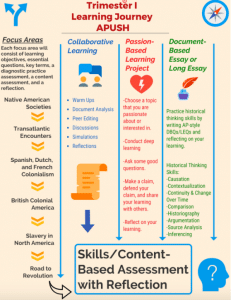

History Teacher and Department Chair Bryan Hunt was the second teacher at our school to adopt learning journeys. Inspired by a recent workshop he attended with Summit Learning in Pasadena, Texas and a personalized learning workshop I ran at Allen, he approached me in the late spring of 2017 about redesigning his AP American History course to give students more control over their learning.

Hunt needed very minimal support shifting curriculum. His greatest challenge was in designing a visual that matched the experience he wanted to create. After a few iterations, he landed on these segments: collaborative learning, passion-based learning project, document-based or long essay and content/skills-based assessment and added focus areas on the side.

Soon after that Hunt decided to build out learning journeys for all three of his classes. “They are the most concise and engaging way to visually explain to students and parents what learning will look like throughout the school year. A learning journey takes the place of a syllabus, a course outline, and a scope & sequence document in an eye catching way,” he says.

Since then, Hunt and I have teamed up with English Teacher and Department Chair Elizabeth Martin, to offer Allen’s first ever Humanities Seminar. We co-created a learning journey in that class as well, dividing the course into three segments: foundational learning, collaborative learning and demonstration of mastery. Just last week, a fourth teacher approached us to see learning journeys from our classes because she has been brainstorming what that could look like for her students.

We aren’t sure where Learning Journeys will take us at Allen Academy. We are excited about encouraging students to make decisions and take a more active role as learners, but recognize that the transition is massive for both teachers and students. Students need to shift their role from passive learner to active decision-maker, which includes a new set of responsibilities. Teachers need to do that heavy lifting to rethink curriculum and assessment, which isn’t easy when things are comfortable. The one thing we do know is that if we’re going to improve upon learning journeys, we’ll need to rely on feedback from students to help us recalibrate as we go.

This story is part of an EdSurge Research series about how personalized learning is implemented in different school communities across the country. These stories are made publicly available with support from Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

See also:

- 10 Simple Lesson Plans for Scaffolding Student-Led Projects

- Kids in the Pipeline During Transition to Proficiency-Based Systems

- Preparing to “Turn the Switch” to a Proficiency-Based Learning System

Mark Engstrom is the head of middle and upper school at Allen Academy in Bryan, Texas.