School and State Transformation in Washington: Lessons from the Mastery-Based Learning Collaborative’s First Three Years

CompetencyWorks Blog

A new report from the Aurora Institute highlights Washington’s deep investment in expanding competency-based education across the state. The centerpiece of this work has been the Mastery-Based Learning Collaborative (MBLC), a demonstration project with 47 schools in 28 districts. The schools receive funding and participate in coaching and professional learning events to deepen their work in MBL and culturally responsive-sustaining education (CRSE). The events bring the MBLC schools together virtually and in-person, building community and a sense of common purpose.

The Mastery-Based Learning Collaborative Evaluation Report – Cohort 1, Year 3, developed with support from the Washington State Board of Education, shares lessons learned from the MBLC’s first two-and-a-half years. It provides evidence and guidance for educators, school leaders, district and state education leaders, and policy makers working to deepen equitable, student-centered learning.

The MBLC’s overarching goal is “to inform future policy by helping decision makers better understand what quality mastery-based learning looks like, how long it takes to implement, and what resources are necessary.” The initiative focuses on advancing MBL and CRSE, which they see as deeply interrelated.

The Aurora Institute has conducted interviews, surveys, school visits, and observations for three years with Cohort 1, the first 23 MBLC schools. The state launched Cohort 2 in January, with 24 additional schools, and Aurora is continuing the evaluation with both cohorts.

Major Findings

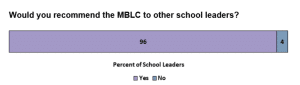

The MBLC showed evidence of promoting deeper MBL and CRSE implementation and positive impacts on early outcomes such as increasing student engagement and ownership, improving school climate and cultural responsiveness, and making learning more authentic and engaging. Almost all school leaders said that they would recommend participating in the MBLC to other school leaders who are exploring transformation to a more student-centered and equitable learning approach.

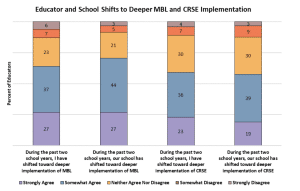

About two-thirds of educators agreed that they and their schools had shifted toward deeper implementation during the past two years, as shown in the figure below. The figure combines all schools, but some schools reported much larger shifts than others due to many interconnected issues such as change management strategies, the school selection process, school size, school leadership, staff readiness and mindsets, and engagement with professional learning.

These figures show just a few out of dozens of areas where the evaluation looks at impacts across key elements of competency-based education. More than 80% of the shifts in knowledge, attitudes, practices, and policies were in the direction intended by the initiative, which strongly suggests that the MBLC is contributing to schools moving toward deeper MBL and CRSE.

The report also shares extensive quotations and insights from interviews with students, educators, school leaders, and state leaders about what’s working, what challenges schools are facing, and their strategies for going deeper and managing change.

Students shared their perspectives on four key MBL and CRSE strategies: selecting learning opportunities based on their interests, learning at different paces, celebrating diverse cultures and traditions, and fostering a more welcoming and affirming school environment. These approaches made students feel more engaged and invested in their learning. Most students wanted schools to expand their use of these strategies, which they said they had experienced at low to moderate levels.

Almost all students agreed that being able to choose important aspects of their learning increases their level of engagement. “Doing my own topic makes me way more motivated,” one student said. “When it’s something I’m genuinely interested in, I put the time in.” The same was true of strategies to create a more welcoming and culturally responsive school climate. Many students made comments such as: “When I feel that a teacher cares about me personally, I am way more likely to be engaged in their class and listen to what they’re teaching me and also do my work at the same time.”

Professional Learning and the MBLC Network

During Year 3, the Great Schools Partnership and the New Learning Collaborative, the initiative’s professional learning providers, offered 27 virtual and live events, provided coaching at each school, and expanded the MBLC website with many resources. School leaders said that the existence of a statewide network has helped them make a case locally for the value of transformation toward MBL and CRSE. The coaching and events also informed and inspired school staff, enabled connections with other innovative schools, and provided guidance that accelerated the schools’ transformation. A fundamental MBLC benefit is that the grant pays for professional learning and collaboration time for school staff.

A school leader said, “The work we’ve done with our coach has been fabulous. It would be very difficult for us to try to do this on our own.” Another school leader added, “The community connection and networking have been the most valuable things for [our redesign process] – being paired at professional learning events with amazing teachers and principals from other schools who are doing innovative work … being able to see tangibly what other people are doing and what’s possible.”

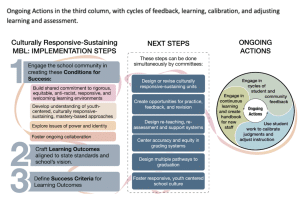

The model guiding the MBLC’s professional learning is summarized in the graphic below.1 The professional learning providers have focused on the first column – creating conditions for success and crafting learning outcomes and success criteria. After schools have those substantially in place, they are better positioned to work on the Next Steps in the second column, although most schools are working on aspects of both columns at the same time. The whole process is accompanied by the Ongoing Actions in the third column, with cycles of feedback, learning, calibration, and adjusting learning and assessment.

Culturally Responsive-Sustaining Education

Most school staff support deepening their CRSE practices, and they described a wide range of activities to improve learning, assessment, cultural responsiveness, and school structures and climate accordingly. In most schools, this work was in its early stages, with deep work still needed to learn more about CRSE principles and practices, use school data to address inequities, and provide needed curriculum, resources, supports, schedules, and planning time.

Some educators and school leaders have experienced pushback or bigotry from staff and community members who object to certain CRSE perspectives or strategies. This has impeded transformation efforts and has prompted some school and state leaders to explore new strategies and messengers in their attempts to shift the mindsets of school staff and community members.

One student made an eloquent case for his school to focus on CRSE more deeply: “We don’t really prioritize being sensitive towards others enough. If we prioritized culture over learning for a few days, we would make way more strides than just focusing on education, because it’s preparing us for the future … and contributing to society.

State Policy and Supports

Washington has several state policies and supports that facilitate MBL and CRSE, including mastery-based crediting, waivers from credit-based graduation requirements, a performance-based graduation option, and the state’s Cultural Competency, Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (CCDEI) Standards for Educators. Recent updates to the state’s teacher evaluation system added elements that align with MBL instruction and assessment practices. Finally, the Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction’s current review of Washington’s learning standards may move the state closer to having an approved set of higher-level competencies and success criteria, which would be a potent catalyst for MBL transformation.

Conclusions and Next Steps

Reflecting the MBLC’s goal to inform practitioners and education leaders at the school, district, and state levels, the evaluation provides more than 20 recommendations for improving the MBLC network, professional learning, and the state’s policies and supports. The lessons shared throughout the report also offer insights for educators and school leaders to support specific practices in areas such as cultural responsiveness, mastery-based crediting, student agency, responsive pacing, habits of success, MBL assessment and grading, and educator collaboration and supports.

While almost all shifts in mindsets, practices, and policies were in the intended direction, it’s also clear that most MBLC schools are in early stages of transformation. This is consistent with the time frame observed nationally for schools to reach deep levels of MBL and CRSE implementation. Washington’s decision to fund Cohort 1 for a fourth year and to launch Cohort 2 signal that the state has seen the MBLC’s early outcomes as favorable enough to continue the pilot, and they recognize that MBL and CRSE transformation is a long-term, iterative process.

¹Created by Great Schools Partnership, Inc., and New Learning Collaborative, LLC for the Washington State Board of Education and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Learn More

- Mastery-Based Learning Collaborative Evaluation Report, Year 3

- Mastery-Based Learning Collaborative Evaluation Report, Year 2

- Community Website of the Washington MBLC

- Washington State Board of Education’s MBLC Web Page

Eliot Levine was Research Director at the Aurora Institute and designed and led the evaluation of the Mastery-Based Learning Collaborative during the three years featured in the report.

Eliot Levine was Research Director at the Aurora Institute and designed and led the evaluation of the Mastery-Based Learning Collaborative during the three years featured in the report.