The Overwhelming Act of Assessing Writing in a CBE School

CompetencyWorks Blog

If you’ve ever been an English teacher, you know what it’s like to teach writing to 95 students who all hold different skill sets in writing.

If you’ve ever been an English teacher, you know what it’s like to teach writing to 95 students who all hold different skill sets in writing.

You know what it’s like to helplessly stare at a pile of 95 essays, knowing that your students need immediate, detailed feedback to guide their revision process.

You also know the frustration of grading those 95 essays, feeling hopeless and disappointed when students are still making the same mistakes as they were on the last essay, even though you went over it hundreds of times during class.

And then revision, arguably the most important piece of the writing process, never happens, because you ran out of time and they had to do it on their own.

And the cycle repeats on the next essay. You cry. You emotionally eat lots of cheese and chocolate.

But because you believe in a competency-based system, and you know that students need to continually practice their writing skills to get better at it, you figure out a better way to teach it.

When I decided to move into a full-press reading/writing workshop with my juniors, I knew what I wanted to happen. I wanted most writing to happen during class, to foster useful and genuine peer feedback, and to make revision a natural part of the whole process.

Before this shift to a workshop model, I’d walk them through the prompt, the rubric, hand out an organizer, model paragraphs, give sentence starters, and do anything else I could think of to help the composition process.

I’d circle the room while students were writing, and then, after a first draft, prompt peer editing groups to stay on task. In pairs, students were hesitant to discuss their partner’s paper beyond spelling errors.

Very few changes would be made from the rough draft to the next. I felt frustrated. Yes, they were “editing and revising,” but their work wasn’t improving and they were still making the same errors, again and again. They weren’t reaching competency.

In this new model, they do.

Typically, a writing workshop looks like this:

I give a prompt. Sometimes it’s analysis, sometimes it’s narrative, and sometimes it’s research based. (I’ve been using Kelly Gallagher’s Write Like This to guide my class this year.)

In class, we all write together. I craft my own piece as my students work, and I talk myself through it alongside them.

We normally spend the first three periods of the process working on brainstorming and writing sloppy, “worst drafts ever.” Some (rare) students write and finish by the second day, spending the next day with their choice books. Some space-out and think on that first day and start a draft the second.

We normally spend the first three periods of the process working on brainstorming and writing sloppy, “worst drafts ever.” Some (rare) students write and finish by the second day, spending the next day with their choice books. Some space-out and think on that first day and start a draft the second.

I still provide everyone with graphic organizers, but everyone uses them in different ways. Some fill it out completely, while others leave it blank and use it to guide them as they write.

By the third day, everyone has something (even if it’s a terrible something) to bring to our editing workshop.

On workshop day, we join together as a class with anonymous drafts. We have a protocol of rules and norms to follow, and we maintain our anonymity by keeping names out of their pieces.

(I credit this anonymous, whole-class model to my former college professor, Liz Ahl. We used it in our creative writing courses at Plymouth State University.)

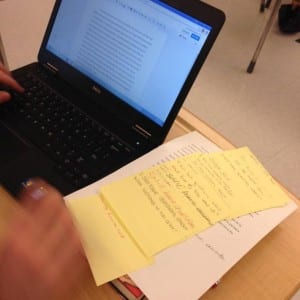

To start our review process, we pass the papers a few times around the circle. First, we mark up the paper we receive with corrections in spelling, grammar, and punctuation. I’ve found that students have a hard time recognizing their own errors in a self-edit, but the act marking up another student’s paper also helps them eventually reflect on errors in their own piece.

Then, we read the lines they loved out loud to the whole group. Compliments in the form of well-written and beautiful lines fly around the room, and then, after we compliment, we begin our constructive criticism.

Then, we read the lines they loved out loud to the whole group. Compliments in the form of well-written and beautiful lines fly around the room, and then, after we compliment, we begin our constructive criticism.

We pass the paper once more for another set of eyes on our conventional errors.

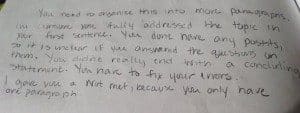

We look at the drafts against the rubric, and the editors are required to write one sentence for every category on the rubric.

The anonymity aspect to our editing workshop is important. Without names in the equation, my students give each other very honest, focused (and respectful) feedback. We talk about the importance of separating our emotions from the work in front of us, and I also remind them when they receive their paper back that their peer-assessed rubric score is not permanent.

Sometimes, we’ll read every draft out loud to the group and critique the piece together. It all depends on what I’m noticing (and looking for) as we’re working through the pieces.

After the drafts are run through our peer workshop, they’re returned to their authors and we pause for a day of in-class revision. Most times, we run papers through our workshop circle just once, with a day of class revision before the papers are published to me.

Sometimes, especially for more complex papers, we’ll run through workshop circle twice, and revise twice before it officially comes to me.

Almost all of our writing and revision happens in class. This causes our deadlines to occur naturally. When everyone’s final draft is done, we move onto the next task.

Because all of our writing happens during class, different classes finish at different times. This means that I no longer have a pile of 95 essays on a hard-and-fast due date. Now, I have a pile of 20 that I can usually get back to them before the next class period.

The workshop-generated feedback is invaluable. It’s more detailed and focused than I could reasonably give on 95 essays, and because of that, my students know exactly what they need to do to make their writing better.

The workshop-generated feedback is invaluable. It’s more detailed and focused than I could reasonably give on 95 essays, and because of that, my students know exactly what they need to do to make their writing better.

I normally spend seven class periods in a full-press writing workshop, which is actually less time than I would have spent if I approached writing tasks in the same traditional way I had before.

After three runs through a full-press, whole-class workshop, I can safely say that this method has produced the Best Writing I’d Ever Graded.

Sitting together in a circle, modeling, and talking together has worked better than any other method I’ve ever used to teach writing, including peer and teacher one:one conferencing.

Even if this process took 17 days, I’d still do it. Because it works.

See also:

- The Power of Choice: Increasing Novel Reading From 21 Percent to 87 Percent

- Choosing and Organizing Content in the SBSC Environment

- Teaching: The Most Intellectual Job in the World

Crystal Bonin is an English teacher as Sanborn Regional High School in Kingston, New Hampshire. She is strong advocate for student choice in reading and writing, and regularly reads and writes obsessively inside and outside of her classroom. In her seven years at Sanborn, she taught for six years within the award-winning Freshman Learning Community, developing competency-based curriculum and assessment. This year, she has been working to overhaul her Junior Lit classroom into a full-press readers/writers workshop. She lives in Kittery, Maine with her husband and cats. Follow her on Twitter at @_readreadwrite or on her blog at www.readreadwrite.wordpress.com.