The Young Women’s Leadership School of Astoria

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the third post of my Mastering Mastery-Based Learning in NYC tour. Start with the first post on NYC Big Takeaways and the second on NYC’s Mastery Collaborative.

The classrooms are buzzing at The Young Women’s Leadership School in Astoria (TYWLS). It’s one of those schools that brings tears – tears of joy as students feel cared for, respected, supported, and challenged throughout their learning. It feels as if students and teachers alike are in what athletes refer to as the “flow state” or the “zone.” Everywhere you look is deep concentration, deep learning, and deep satisfaction.

TYWLS is using mastery-based learning to break out of many of the organizational structures that bind, and one could argue constrain, our education system. Thanks to Dr. Allison Persad, principal; Caitlin Stanton, arts teacher; Christy Kingham, ELA teacher; Scott Melcher, social studies; Katherine Tansey, math teacher; and Greg Zimdahl for sharing their insights and wisdom.

The Power of Performance Levels

The Young Women’s Leadership School of Astoria, serving 600 students in grades 6-12, is ten years old. Watch the film to hear from the young women of TYWLS directly.

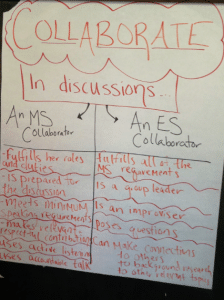

The Young Women’s Leadership School is focused on skills such as Argue, Be Precise, Collaborate, Communicate, Conclude, Discern, Innovate, Investigate, and Plan. These skills are the primary organizing structure for the school. ELA teacher Christy Kingham was the first to explain the TYWLS strategy. “We began to integrate project-based learning and performance tasks at the same time as we came to mastery-based learning,” she said. “We stay focused on helping students build skills, as those can be transferred into other domains. Content in each of the disciplines is very important, as that is what students use to engage in projects and performance tasks. However, we separate skills from content because of the importance of transferrable skills.”

All teachers use the same rubrics for each of the ten skills that indicate performance levels 6-12. In some cases, such as ELA, they are organized around bands 9-10 and 11-12 rather than grade levels as indicated by the Common Core ELA standards. TYWLS refers to these as spiraled rubrics that are organized and vertically aligned so that students can see their skill development over different performance levels. Thus, an eighth grade student can meet the eighth grade performance level, or they can exceed by meeting the ninth grade performance level. When they enter ninth grade, if they have developed any additional skills, they are now meeting the ninth grade performance level and can strive to meet the tenth grade level. One teacher explained, “Spiraled rubrics allow you to batch by skills, not just age. We can work strategically to help students move from one performance level to the next.”

The TYWLS commitment to personalizing instruction is reflected in the design of the rubric. The Not Yet category on the rubric is left blank, with descriptions for only the meet or exceed categories. Kingham explained, “There are a million reasons why a student is not meeting a learning target or what they could be doing on the way to meeting it. We leave it blanks so that teachers can give individual attention and feedback.”

Benefits of Skills-Focus

There are several other benefits from this focus on skills and schoolwide spiraled rubrics. First, the skills-based learning targets aren’t just for grading students. They become “teaching points” that help teachers become more intentional in their instruction and in preparing for helping students in the places they are most likely to struggle. Second, it lends itself easily to interdisciplinary learning. “We all can access the learning targets across the school,” drama teacher Caitlin Stanton explained. “It makes it easy to figure out ways to create joint targets. For example, in science, students are formulating an argument and defending it with evidence, as are students in a social studies or English class. Shared targets create shared language and expectations and push students to truly transfer these 21st century skills.”

The skills-focus also offers teachers flexibility in content as well as opportunity for substantial voice and choice. As one teacher put it, “The content choices can be externally driven by state policy or internally by the interests of students. The content lives in the evidence that students create to demonstrate their learning.” Teachers draw on content in terms of what they think will engage students and offers opportunity for exploring issues and building skills. Of course, in New York, teachers are also cognizant that they have to cover the content as required by the Regents exams. History teacher Greg Zimdahl explained, “In my US History course, I use a project entitled ‘Becoming American,’ which uses six different genres to explore immigration with students making presentations to an audience. We are folding in all the content they need to cover for the Regents and students will be able to co-design projects.”

The number of learning targets is also kept at very manageable numbers. TYWLS largely annualizes learning targets, which range from nine to fifteen per year. There have been concerns that using standards as the primary organizing structure in any school (and especially in competency-based schools) creates too much granularity if teachers are assessing for every standard.

Benefits for Students

It makes a difference for students to have a sharp focus on such a powerful set of skills. For starters, interdisciplinary courses are going to have more depth, especially when driven by fascinating essential questions. Second, reflecting on and building a small set of skills gives students confidence. As Greg Zimdahl explained, “Test anxiety can go away when students are confident they have the skill. So many exams are about content and trying to remember all the content. We remind students that if you forget the facts, you still have the skill.”

Students can also build up evidence of meeting targets in one class and submit to a teacher of another class. This is particularly important when students are coming from behind and have performance levels significantly lower than grade levels. Teachers can see each other’s learning targets and enter information on students’ progress in JumpRope, their grading information system.

A conversation with Rodyna, Misbah, and Naimah, students who range from eighth to twelfth grade, illuminated the value of the mastery-based grading practices. Misbah explained, “Mastery-based grading makes the relationship between the student and teachers more intimate. It becomes a two-way relationship rather than a one-way relationship where the teachers just give you the grades. I can talk about my struggles with my teacher in a very clear way that is focused on specific skills and specific performance tasks. I know what I need to do in order to get the grade I want.” Rodyna added, “The mastery-based grading helps me understand what I need to learn or do differently. In the old way, when I got a number, I wouldn’t know what to do differently. With the learning targets, I can make better choices and revise things.”

All three young women chimed in when we talked about how grades reflect them as learners. “A number can’t represent a person. An average doesn’t reflect who you are. Mastery-based learning shows how we are doing in our learning.” Misbah also pointed out that “the numbers can get in the way. I just wanted to get higher and higher numbers. I wasn’t very interested in building my skills. It was the easy way out. It’s harder this way, to really make sure you are learning, and it is better.”

Beneficial Schoolwide Practices

The spiraling rubrics for skills require two schoolwide practices, not usually found in traditional schools, that can help drive toward mastery-based learning. First, ongoing calibration is particularly important for teachers to credential the different performance levels of each skill consistently. Second, given the flexibility in content, TYWLS is beginning a process of curriculum mapping to look at what content is being covered in each grade. Teachers are beginning to capture the overall curriculum, including topics, essential questions, performance tasks, and the evidence of learning submitted by students. Kingham said, “We are trying to capture the overall student learning experience so that we can become more intentional.” This is an important practice for several reasons: to avoid unintentional duplication, to seek out opportunities to build upon and connect with interdisciplinary curriculum, and to ensure enough breadth.

As TYWLS continues to fine-tune their processes, the teachers are also building confidence. Kingham reflects, “Mastery-based learning help to put to rest the anxiety we feel about how we can know what our students know.” Relying on processes that allow superintendents, principals, teachers, and parents to have confidence that teachers know what students know is one of the cornerstones of embedding accountability into our schools rather than depending on policy to drive it.

Insights and Inquiry: Of course, when students have choice within their performance tasks, there will also be differentiation about the background knowledge (content) that each student brings to the classroom. It’s important for skill-focused schools to keep an eye on the content that is being used – not covered, but used – in the classroom. I can also imagine students beginning to map out the content they are familiar with so they have a growing understanding of the background knowledge they have learned from their life experiences as well as in school.

Simultaneous Skill Building and Preparing for the Regents

Wherever I went in NYC, all schools said the same thing. The global history Regents exam is considered a barrier to mastery-based learning. One teacher explained, “You get students in ninth grade and you have two years to flood them with content regardless of what their skills are.” TYWLS’s skill of “Be Precise” is one of the ways they help students build a skill and come to terms with the idea that they are going to have to remember a lot of facts. Stanton noted, “Discern is also a powerful skill for preparing for the Regents. Students need to be able to read text and make meaning from it.”

Students’ reading skills are important in this process. Zimdahl explained, “We have had to build our ability to support literacy across the curriculum using guided text and close reading.”

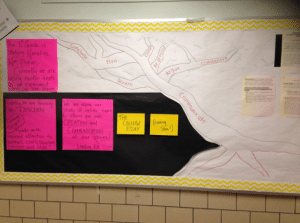

You can get a glimpse at how this all comes together by looking at Zimdahl’s course on The Story of American Freedom for eleventh graders. At the end of the course overview, Zimdahl explains that he’s designed for three purposes: to engage in a study of America’s past, to prepare you for college-level work, and to prepare for the American History and Government Regents. However, note that the goals of the course are for students to become skilled, lifelong learners. If you go to unit one on the colonies, you can see how he organizes units so that they are “asynchronous” (i.e., students have flexibility about pace with the understanding that every student needs to be planning for what it will take to complete the course). There is also a performance tracker for students that lists the performance tasks in each unit and an example of a rubric that shows the three categories of Not Yet (open for teachers to provide feedback to students), Meeting, and Exceeding across four skills: collaborate, conclude, discern, and plan. Again, given the spiraled design of the rubrics, Meeting equals eleventh grade and Exceeding means students are demonstrating at the expectations for twelfth graders.

Intensives for Deeper Learning

Twice a year for two full weeks, cross-disciplinary teams of teachers create intensives for students to take a deeper dive into project-based learning. Students get to do things they might not otherwise (given the constraints of school schedules) while also earning one elective credit. Students get to choose among all the intensives, although teachers will encourage students weak in an academic area to focus on something that will allow them to build their skills.

The intensives, like the classes, are organized around essential questions, performance tasks, and assessments of the ten skills. For example, the essential questions driving the intensive Citizen Food 2.0 are:

- How is food a reflection of a society’s values and priorities?

- How does food serve as a foundation for individual, community, and environmental well-being?

- How can food be an avenue to empowerment, citizenship, and social justice?

The performance tasks or deliverables (that’s the first time I’ve seen that word used in a school) include:

- “What I Eat” Photo Essay

- Journal Entries

- Farmscape play performance

- GMO Debate

If you are interested in creating intensives for your school, check out Kingham’s resources available to support teachers in creating their intensives.

Meeting Kids Where They Are

Kingham was adamant, “I do not change my text for any student.” As we entered the conversation about how to meet the needs of students with significant gaps in their learning, Kingham described her approach. “Students have to have text-rich experiences and lives. We want them to have the skills and attitudes that allow them to read anything. I design scaffolding strategies to do close reading for those students who are challenged by complex text. They have to be practicing the skills and performing the skills all the time. Students who struggle with reading have to practice and perform reading strategies the same way that we have our ELL students practice and perform Romeo and Juliet.”

Zimdahl explained that this approach does require “smart planning,” as she has to be prepared for multiple things to be happening in the classroom. In addition, she has to think about the pacing for the class, knowing that some students may take longer to read the central text. Thus, she needs additional activities for other students when they have finished the text. Stanton explained “We lean hard on the Weebly for each course to make it easy for students to find out what other activities they can do. We strive to make our courses completely asynchronous. In order for teachers to personalize in the classroom, we have to hand over the keys to learning. We want students to be responsible and purposeful in their learning. It can be stressful for teachers and students when you do it for the first time. It doesn’t feel or look like learning, but then the products start rolling in. Students can do so much more than we think they can.”

Preparing Teachers for Personalized, Mastery-Based Learning

Our policy talks about all students being ready for college and careers, but we don’t talk as much about what it takes for all teachers to be ready to succeed in a personalized, mastery-based school. At TYWLS, all the teachers have embraced mastery-based learning. However, Kingham noted, “There is a difference between your mastery infrastructure and the school capacity. As teachers, we are always building new skills – that’s an ongoing process, but we are all in.” One teacher described their culture as, “There are always a few teachers who are cheerleaders helping to carry the others through any new change or improvement. Each improvement means we need to learn new skills. So it helps tremendously when we support each other.”

When they hire new teachers, TYWLS seeks those with an open mind, a shared understanding of pedagogical approaches, and a willingness to learn. However, it can still be a bit of a struggle as teachers shake off the assumptions and routines of the education system that they themselves learned in. Principal Allison Persad noted, “We are asking people to go beyond the history of their life experiences. We are asking them to change how they think about teaching, learning, and their role as teachers. We are asking them to make the mindshift to mastery.” Kingham continued, “If a teacher’s mind and heart is in the right place, and once we give them time to see mastery-based learning in action, they can move forward. The other teachers will support them.”

The team at TYWLS pushes themselves to improve the models and processes. Persad noted, “We expect students to revise and revise and we ourselves are in a constant process of revision. How can we deepen the learning? How can we better engage students? How can we offer them even better learning experiences? There isn’t a perfect mastery-based system. It’s a process of continually improving.”

It was interesting to hear about the steps TYWLS has taken in their continuous improvement efforts. Starting with support from Grant Wiggins of Authentic Education, they learned how to develop outcomes and essential questions. Purchasing JumpRope allowed them to track student progress on outcomes. They also realized they were missing the 21st century or higher order skills, thus the shift to using the ten skills as outcomes. Along the way, they introduced student-led conferences. Only last year they realized that the ten skill outcomes were too broad, so they created learning targets. Every course has about nine to fifteen learning targets for the year (three to five per trimester). They created the spiraled rubrics. And now…beginning the process of curriculum mapping across the school.

See also: