Time to Tackle the Elephant

CompetencyWorks Blog

Why do we continue to teach students grade-level standards based on their age when their skills are actually two, three, or more academic levels lower?

Why do we continue to teach students grade-level standards based on their age when their skills are actually two, three, or more academic levels lower?

In states and districts across the country, educators are frustrated and wondering why their students aren’t able to learn algebra as demonstrated on state accountability exams. There are conversations about redesigning the courses, more remediation, and even questions about whether the exams are too hard or the expectations too high. All of it assumes that algebra should be taught in a specific grade and that we will just keep teaching it to kids over and over again until they get it. What’s that saying about insanity – Doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results?

Competency education suggests another solution: Ensure that students have all the pre-requisite knowledge and are able to engage in skills based on where they are, not where they should be. When we teach them in their “zone” of proximal development, it is personalized learning (or student-centered if you prefer that language). When we teach students based on their grade, we are using the batch method of the antiquated factory model. It may help some students just to have more time and instruction to learn algebra. But for some who may have been passed on to the next grade without becoming proficient or who may have missed concepts along the way due to lack of class attendance because of housing instability, being in the child welfare system, or suffering from poor health, they may need to work in their zone to build up the pre-requisite skills.

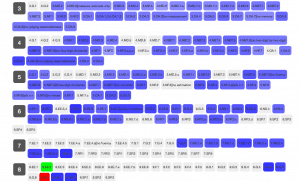

For example, if you are going to dig into learning how to create equations in high school algebra, you are going to need to draw on a lot of skills you learned in early elementary school. (Check it out on the flow view of interdependencies of math standards.) Depending on where students are in building up their toolbox of standards, they are either ready to tackle algebra, need a bit of brushing up, or need to develop additional tools.

Is it really the best idea to use the precious time and resources of the school year to cover a set of standards knowing some students are going to be unlikely to become proficient because they are missing the pre-requisite skills? Shouldn’t we be spending those same resources helping students build their skills starting where they are, and making progress from there? In the first scenario, students continue to feel that they “dumb,” teachers are frustrated, and there is little organizational learning or instructional improvement. In the second scenario, students feel successful, are more motivated to keep trying, are learning the skills they need for the next set of learning…and who knows? They may have one of those big leaps of learning and start to catch up. Teachers will feel that warm glow that brought them to teaching in the first place when students are learning and taking pride in it.

Seeking Better Understanding and Solutions

In my travels this year to competency-based districts and schools, I was a bit taken back that proficiency-based districts and high schools continue to feel pressured to “cover” the grade level standards even though students are entering school with significant gaps or skills at elementary level. Even first grade teachers described the pressure to cover the standards when students’ development suggested a different instructional path.

I think it’s time we tackle this problem. It’s hurting kids and it’s undermining the belief in adults that we are “doing right by kids.” However, it’s not necessarily an easy problem, as there are multiple components and perspectives. Here is a quick breakdown of the issues I think we need to begin to think through:

1. What makes the most sense in terms of instruction? The current practice in serving students who are behind is to engage them in instruction around grade level standards with a combination of scaffolding, double-dosing, and/or additional support such as afterschool tutoring. How effective are these strategies? Does the effectiveness vary whether the student is operating at a much lower academic level as compared to only one grade level lower? Does it make a difference if the student has some familiarity or if it is an issue of fluency? And….how might this vary across disciplines and topics within a discipline?

How do these traditional strategies compare to more personalized ones? Might we see greater gains if students receive instruction in their “zone” as compared to grade level? How might we build in greater instructional time without the expectation that students must fail in order to access summer school or additional tutoring?

I also wonder how much the research on learning progressions might help us in creating new solutions for students who are at lower academic levels than their age-based grade. Are there instructional strategies that can help students build up the pre-requisite skills specific to the standards? Or do we need more research to better understand how a ninth grader might revisit fractions to build up their understanding of the mathematical concepts as compared to when they first were supposed to encounter them in elementary school? Are there instructional strategies that can help accelerate learning for students who don’t have the skills they need for their grade level?

2. Social-emotional learning, rebuilding a growth mindset, and maturity. In the traditional system, by middle school (or tragically sooner), there is a group of students who think they are dumb. They may even think of themselves as losers. Perhaps they just don’t think they are good at math or reading. To help them fully engage in learning, we have to not just help them learn the growth mindset, they have to build up the social-emotional skills and courage to overcome their own fear of failing and taking risks. For students whose lives have been shaped by trauma, the emotional reaction to failure may be much more than an adult might imagine.

We need to begin to think more deeply not only about engagement and motivation, but about strategies for those who have already disengaged. How might we think about their trajectories? Are there strategies and practices that help them build up their social-emotional skills more quickly? Perhaps we should look outside the education system to better understand the youth development strategies that could be beneficial.

3. Policy barriers and new policy constructs. It is very clear that the state accountability exams (especially in conjunction with the current policies around teacher evaluation) are holding “coverage” in place. It is imperative that we create adaptive systems of assessments so students take summative assessments after teachers have determined they are proficient. It is a total waste of resources and likely damaging to children to be forced to take a test that does not contribute to their learning when everyone knows they are going to fail.

What other policies need to be looked at? Certainly we need to think more creatively about how high school and high school diplomas. What happens if a student reaches proficiency in college and career readiness in most but not all domains? If a student enters at the sixth grade level and reaches proficiency at eleventh grade but not twelfth, should they be awarded a diploma? Might we create personalized trajectories where students who enter without adequate skills have opportunities for more instructional time on Saturdays, in the summer, or during additional years? Might we create diplomas that indicate what students know and can do, clarifying if they are ready for college level courses without remediation or access to technical courses or training?

Of course state and district budgeting is an important policy to reconsider, as we want to make sure that students who are over-age and undercredited (students in foster care, with high mobility, who had to take time to work or take care of siblings, or who simply got lost along the way in the transition to high school) have opportunities to re-engage and complete their education.

4. Framing. It’s hard to talk about these issues because we don’t have common language in either general or specific terms. A starting point might be the following three frames:

- A personalized approach where students receive instruction based on where they are on a continuum of expectations (i.e., standards). We could talk about a student’s zone as the academic level and specific standards they are working on.

- The traditional, batch-approach of the factory model driven by the age and grade of the students. This is the “coverage” strategy we are currently in that is reinforced by the state accountability exams.

- A “recuperative approach” that is in some ways a hybrid that would strategically organize learning based on where the student is in terms of age and grade level, the amount of time they have left before they age-out of the K-12 system (and their ability to continue to pursue their education), and the necessary learning for them to get as far as they can as fast as they can.

Are there other frames that help us to challenge assumptions that shape our understanding of what is possible? What are the other elements we would need to create common language around to help us understand each other as we talk about how we are helping students who are “off-pace?”

Tackling the Elephant

When I look at this list, it is clear to me that one convening or paper isn’t going to resolve these issues. We need to be the blind men with the elephant. We need to gather together people with lots of different expertise and perspectives to explore these issues in bits and pieces and then put our ideas together.

This would be a complex inquiry over a year or two (we can’t wait for one of these five year processes) to explore the leg, trunk, body, and tail of the elephant. If we share our insights along the way, we can generate even more inquiry and, with the help of creative designers, thoughtful practitioners, and open-minded experts, we can figure out how to organize learning that really and truly meets the needs of students who happen to be where they are in their learning and not where we expect them to be.

My suggestion is to organize four to eight organizations, with each working on two of these chunks of the problem. Their goal would be to convene people with diverse expertise and perspectives (and that would include racial and culture diversity as well) to deeply understand the different aspects and, if needed, develop further research agendas.

Anyone want to join us in this inquiry?