Warning: Delayed Graduation Possible

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post originally appeared at the Foundation for Excellence in Education on February 23, 2015.

MINIMUM GROWTH WARNING: AT YOUR CHILD’S CURRENT RATE OF PROGRESS AND ACHIEVEMENT LEVEL ON THE STATE ASSESSMENT, THE PROBABILITY OF YOUR STUDENT GRADUATING ON TIME IS _____ %.

What if parents received these notices on their child’s report cards?

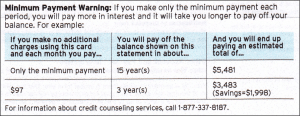

Since 2009, every credit card bill in the United States has been required to notify consumers exactly how long it will take to pay off the debt if making only the minimum payment. This was mandated by Congress in order to establish fair and transparent policies related to consumer debt.

Isn’t a child’s education just as important? Don’t we owe full disclosure to parents and educators? Don’t they deserve fair and transparent information?

As Julia Freeland from the Clayton Christiansen Institute properly notes, “Annual expectations for student progress are deceptive because they are benchmarked against the assumption that students begin each year having mastered the previous year’s material. However, for students who do not make a years’ worth of progress in a given year, they will need to make that up in subsequent years. Indeed, the further behind a student falls, the more progress he will need to make annually to graduate on time. For many students, this does not add up to a diploma. But worse, few receive the warnings—or the necessary supports—ahead of time to prevent this.”

As soon as the reality of school accountability set in, the debate over proficiency versus growth began in earnest. The goal, and I believe, the greatest feature of school accountability was to bring transparency for the first time to the academic performance of ALL kids.

Many people still believe the expectation of 100 percent proficiency set by No Child Left Behind was unrealistic. But maybe the conversation should have less to do with our preconceived notions about the ability of children and instead focus on whether our decades old, one-size-fits-all model of education can accomplish the goal. Being serious about proficiency for ALL students will require a system with enough flexibility to meet the needs of all students.

Fortunately, we now have more innovative, personalized approaches that allow students to demonstrate what they know and to progress at a flexible pace. But such an approach raises new questions over how to measure and ensure sufficient progress towards proficiency.

But what is sufficient progress? Is one-year’s growth enough? It’s definitely a minimum expectation. What about 1.5 years? At a given rate of growth, how long will it take to achieve proficiency? To graduate? Students in states with high-stakes exams have been acutely aware of this tension. Can we give the allowance of time without slipping into the temptation to lower expectations?

Care is needed to balance the desire to allow students to progress at a flexible pace with the need to ensure that all students will achieve proficiency and graduate on time. And this will exacerbate the tension between an emphasis on achievement or growth in accountability models.

I am confident that new types of growth measurements will be developed, but in the meantime can’t we start with increased transparency? Let’s be honest about a student’s trajectory, and then maybe we can have an honest conversation about what it will take to actually help students achieve proficiency.

Transitioning to a competency-based system of education will provide the framework and context necessary for this conversation. Requiring actual demonstration of proficiency for student progression, credit and ultimately diploma decisions will increase transparency and force us all to recognize where students really are and what they really need to succeed.

Karla is the State Policy Director of Competency Based Learning for the Foundation for Excellence in Education. Previously, she served as Special Assistant to the Deputy Superintendent of Policy and Programs at the Arizona Department of Education. Karla also served as the Education Policy Advisor for Governor Brewer and as the Vice-Chair of Arizona’s Developmental Disabilities Planning Council. Her experience includes serving as Director of State Government Relations for Arizona State University (ASU) and as a senior policy advisor for Arizona’s House of Representatives. Karla received her B.A. from Indiana University and an M.P.A from Arizona State University. Contact Karla at Karla (at) excelined (dot) org.