WestEd’s Student Agency in Assessment & Learning Project

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post is adapted from the Next Generation Learning Challenges‘ Friday Focus.

This post is adapted from the Next Generation Learning Challenges‘ Friday Focus.

Last week I had the pleasure of joining about 30 educators for the summer leadership session of WestEd’s Student Agency in Assessment & Learning (SAAL) project. Like many professional learning experiences, we spent some time watching classroom videos. But this time, we were instructed not to focus on instruction. Instead, we watched the students, who were giving each other feedback about strategies to decompose three digit numbers. Not checking answers, not checking procedures — discussing the pros and cons of how each student approached the problem.

Though there are many definitions of student agency, there’s nothing like seeing it in action.

WestEd’s SAAL project is a part of the Assessment for Learning Project (ALP), an initiative led by the Center for Innovation in Education in partnership with NGLC. The projects in the ALP network range from individual schools to state-level initiatives, but from different vantage points and with different levers to pull, they’re all asking the same core questions:

- How can we design and implement systems of ongoing formative assessment that support student learning, rather than simply evaluating students?

- How can we go beyond academic achievement to measure a broader range of the skills and dispositions necessary for success in college, career, and community?

- How can assessment empower students to develop greater agency in their own learning?

The SAAL project asks how formative assessment practices — at both the teacher and student level — can contribute to learner agency. WestEd is working with three districts – Chandler Unified and Sunnyside Unified in Arizona, and Blachly School District in Oregon – to explore how teachers can cultivate student agency in learning and assessment. All of the participant teachers in these districts completed the six-month online digital learning experience, Formative Assessment Insights developed by the SAAL team and funded by the Hewlett Foundation, which laid the foundation for the current project.

Like all ALP projects, SAAL is testing a hypothesis, and it’s too early to draw final conclusions. But I was struck by the way that the WestEd team is structuring their inquiry. Through action research in close partnership with teachers and instructional leaders, they’re examining two essential issues: What does is truly mean to be “student centered?” And, how we need to think differently about instructional design and assessment to cultivate student agency?

The Power of Focusing on Student Learning

As part of the SAAL project, teachers will record videos of their classrooms, and use these videos to reflect on the learning behaviors students are engaged in. Specifically, teachers will focus on the degree to which students are self-assessing, and engaging in peer feedback discussions. The WestEd team has developed a prototype “continuum” of observable student behaviors related to these two learning practices. The project lead at WestEd, Margaret Heritage, noted that when people “rate” the teacher in the video we watched using rubrics for instructional practice, the ratings are uniformly high. But when they use the continuum of student behaviors, the result is much more mixed.

While focusing on quality instruction is crucial, this observation illustrates that great instruction doesn’t necessarily lead to deeper learning for every student. As the WestEd team points out in their research brief How Students Learn…To Learn, deeper learning truly takes hold when the student herself perceives a gap between where she is and where she wants to be, and takes action to close that gap. In other words, great instruction only takes a student so far. Agency, cultivated over an extended period of time, allows students to make the most important connections and decisions themselves.

As one participant in the summer leadership session told me, “The focus on learning rather than teaching forces us to think about how to engage with students in real time — on how to make students creators rather than consumers of learning.”

The Power of an Explicit, Coherent Research-Based Theory of Learning

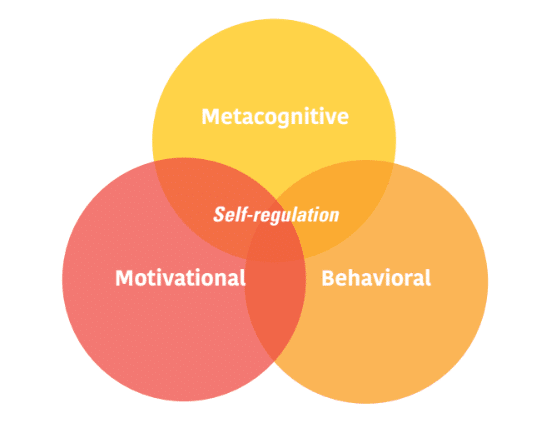

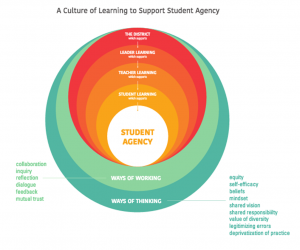

The distinction between “learning” and “teaching” is at the heart of the NGLC vision, and at the core of most NGLC school designs. What makes the WestEd project so powerful, in my mind, is how clear and coherent the project is about the theory of learning at the center of this work. Drawing on the research base for “self regulated learning,” WestEd summarizes their framework for student agency in the following diagram:

How Students Learn…To Learn gives a very accessible summary of the research base behind the SAAL team’s theory of student agency. As explained in the brief, student agency emerges from the interaction of three factors (rather than any single factor alone):

- Metacognitive practices (e.g. goal setting, monitoring progress toward these goals, reflecting)

- Motivation and feelings of self-efficacy

- Behavioral changes (e.g. seeking out help, finding a quiet place to work).

To paraphrase one of the participants in the leadership session, the aspiration to have students take ownership of their learning is nothing new – we’ve been talking about it for years. But by being clear about what we really mean by agency, we can explicitly draw it out to drive our classrooms. As the December 2015 NGLC Twitter Chat illustrated, there are a multitude of conceptions of student agency. Finding an entry point can be a challenge.

The SAAL team’s framework for student agency helped them prioritize self-assessment and peer feedback as the focus of the project. These are by no means the only practices that contribute to agency, but they are sufficiently specific, observable, and research-based that any teacher can begin them to design learning experiences that cultivate student agency.

The Power of a Learning Culture

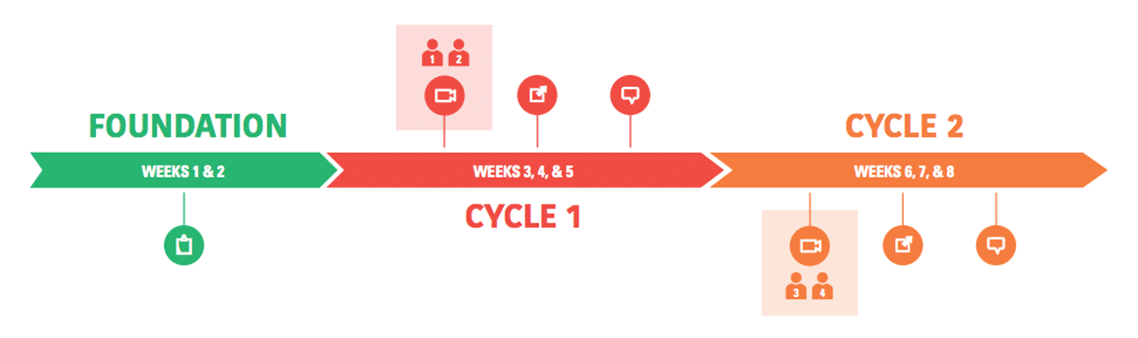

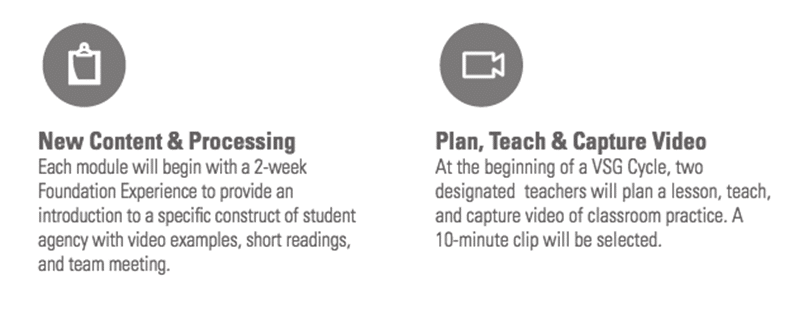

The SAAL project is built around 8-week Video Study Group modules, illustrated in the diagram below:

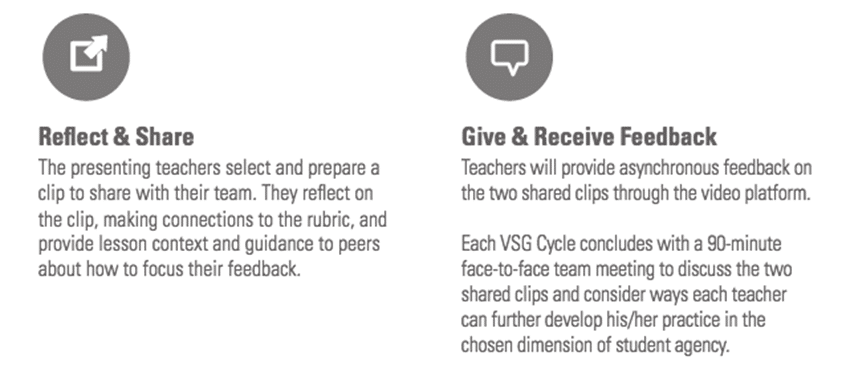

In small teams, teachers spend the first two weeks (“Foundation”) learning about the project’s construct of student agency. Then, pairs of teachers run through two three-week cycles in which they capture video of their classroom, self-assess using the continuum, and then give & receive feedback. The continuum is structured like a rubric, but it is not designed for evaluation or scoring. Instead, it’s a tool for teachers to self assess, and to have peer feedback discussions about learning in their classrooms which lead to next steps in teachers’ practice.

It’s not coincidental that self-assessment and peer feedback are at the heart of the adult learning model, too. The project’s theory of action is based on research showing that student agency emerges from a culture of learning, as shown in this diagram:

As detailed in WestEd’s brief Teacher Learning: Your Link to Student Learning, a learning culture is fed when adults and students engage in certain ways of thinking and ways of working. The WestEd team referenced the work of scholar Sue Swaffield from the University of Cambridge England, who has argued that teachers who develop their own practices (rather than following scripted instructional guidance) are more successful in implementing formative assessment, and their students display more self regulation. In other words, adult agency leads to student agency. Instead of recommending certain instructional practices, the Video Study Group protocol provides a structure for teachers to collaboratively generate their own strategies, fueling a true culture of learning.

My Reflections

None of these concepts were wholly new to me, but seeing them all together in a way that so coherently links research on learning to actionable strategies for cultivating learner agency was incredibly powerful. Throughout the Assessment for Learning Project process, we have sought to “walk the talk” by committing to a learning culture. The SAAL Leadership Session pushed my thinking about what it really means to support this culture.

When I talk about what we’re learning as an initiative, am I referring to a collection of best practices, or to how we grapple together with complex questions (without necessarily finding answers)? How can I be more intentional about assessing my own contribution to this learning and creating spaces for authentic feedback with my colleagues? I’ve never been afraid of not knowing “the answer,” but after learning with the SAAL team, I’m redoubling my commitment to plunge into the most challenging questions – because the more we all do this, the more the students who depend on us will, too.

See also:

- How Next Gen Learning Can Support Student Agency

- NGLC Schools Take On Competency-Based Learning

- Supporting Student Agency Through Student Led Conferences

Tony is a Program Officer for NGLC.