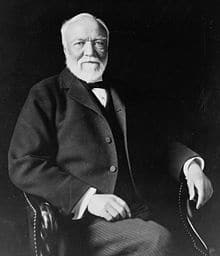

What Would Andrew Do?

CompetencyWorks Blog

(See the second post on this topic Beyond the Carnegie Unit)

Earlier today, the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching (CFAT) released their report The Carnegie Unit: A Century-Old Standard in a Changing Education Landscape. [Disclaimer: I was a member of the Advisory Committee.] It’s a beautifully written report with sweeping historical context and fun little details. (Why is liberal arts college four years? Because CFAT, in designing the requirements for institutions of higher education to have access to Andrew Carnegie’s pension plan, said so.) It’s a must-read for the summary of how competency education is evolving in the K12 and higher education sectors.

However, if you are expecting something as big and bold as Andrew Carnegie himself would dream up, you’ll be disappointed. In fact, I imagine that deep under the snow in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Tarrytown, New York, Andrew Carnegie is wishing he could find a way to join the conversation.

It’s easy to agree with the findings—that Carnegie Unit (CU) rarely acts as an actual barrier, as in actually prohibiting innovation, with a few important exceptions such as federal financial aid. However, there is an enormous difference between an idea acting as a barrier and catalyzing improvements in the education system. In focusing the scope of the report on whether or not the CU is a barrier to improvements, CFAT trapped themselves in either-or-ness, rather than engaging in an open inquiry into how we might be able to move beyond the confines of the CU to a more equitable, flexible, and transparent system. Even an analytical report that takes us up close to how the CU operates in administering the education system, specifically higher education, would have allowed us to think more deeply about how to re-engineer the system.

Those of us who have come to terms with the fact that the traditional system—time-based, A through F, age-based advancements—is stifling our students and reproducing inequity are seeking a new language of learning that tries to capture pace, rate, trajectory, and depth of learning. There is none to be found in this paper—not even how we might even begin to think about a new common language of learning.

CFAT made several choices that backed themselves into a corner. First, they insist that we look at the CU in isolation of the other elements of the system, such as grading. They argue that the CU “was never intended to function as a measure of what students learned” and has been “miscast as a measure of learning.” Yet, the education system has interlocking pieces, making it difficult to understand any one piece in isolation. Certainly, CFAT had to select what they would focus on and what they wouldn’t. But to try to separate the CU from the grading system is like a doctor trying to assess one’s health based only on your HDL cholestrol without taking into account your LDL. A student takes a class, they get a grade. If the grade is high enough, they they receive a credit, indicating some acceptable level of learning to take the next class. When colleges use the CU for estimating faculty costs within a budget they are making an assumption that in fact the students will learn — not just be exposed to the content.

There is even indication that CFAT itself is somewhat ambivalent about their position that the CU does not indicate learning. In the conclusion, they suggest otherwise, “Whatever the challenges the Carnegie Unit may pose, in its absence there would be no common language to organize the work of schooling and communicate student accomplishments across a wide range of institutions.” Student accomplishment? Isn’t that what students have learned or can do? Isn’t that an indicator of learning?

Second, although they firmly state the CU is not an indicator of learning, they also want us to see its value as a currency or medium of exchange. Yet, it’s not clear what its value is beyond instructional time or a proxy for student exposure to content. They suggest that the system might fall apart without the Carnegie Unit without ever taking us through what might happen if we did change, eliminate, or modify the application of the Carnegie Unit. What would happen if we said that the CU was based on a student becoming proficient rather than the amount of time of instruction, as New Hampshire has done? Wouldn’t registrars still be able to use a credit to schedule students and create transcripts?

I think that is where I had the most difficulty with the paper. CFAT asks us to accept the CU simply because the system has developed around it. We are asked to accept the CU as an indication of instructional time in a world in which instruction is being delivered online, in which students can watch a video of a lecture rather than the lecturer themselves. We are asked to accept its value as a currency when we all know that districts and colleges can decide whether or not to accept credits from other schools. We are asked to have students seek to accrue credits that have no meaning.

Across the nation, there are educators coming together and deciding they need to do what’s right for kids. They don’t know what exactly the new system will look like, but they know for certain the traditional one isn’t working, just as Andrew Carnegie and his colleagues knew that there could be a better system of education. A century ago, the emphasis was on standardization, while ours is on personalization so that each student receives the support they need to succeed.

Once upon a time, there wasn’t a CU, and someone created it. And now we are going to create a new set of language of learning. It will take an enduring commitment to our students and a big dose of courage and imagination.

I think the title of the next paper should be What Would Andrew Do?