Old Habits Die Hard: How to Build New Moves and Habits to Sustain Change

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post is part of a series inspired by the new report: Teachers Making the Shift to Equitable, Learner-Centered Education: Harnessing Mental Models, Motivations, and Moves.

Even when we are equipped with a clear plan of action and have high motivation and support, as humans we can still struggle to adopt new practices. This is true for educators, and professional learning should be designed with this in mind. Educators need to know which skills to focus on and have the chance to apply these new ideas in practice as they systematically develop them over time.

In addition, old, ingrained habits of practice—which may be counter to new approaches—can insidiously thwart educators’ efforts to change, especially when these habits remain unexamined.

We have all seen it. We have all been there. Amidst the day-to-day challenges of teaching, how easy is it for an educator to revert to autopilot and respond “good job” or “that’s correct” when a student answers a prompt, rather than nudging the learner’s use of metacognition and reasoning with “tell me more about how you came up with that?”

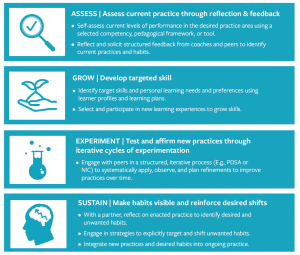

Designers of professional learning can enable educators to build new moves and habits to sustain change, by engaging them in exercises designed to (also see figure below):

- assess current practice through reflection and feedback,

- develop targeted skills,

- test and affirm new practices through iterative cycles of experimentation, and

- make habits visible and reinforce desired shifts to sustain change.

How to Build New Moves and Habits to Sustain Change

Assess: Assess Current Practice Through Reflection and Feedback

Before we can identify specific learning goals, it is necessary to assess the current status of our practice and the extent to which it aligns (or conflicts) with our desired practice, standards, or goals.

The role the adult learner plays in the feedback process is a key but often overlooked element. The adult learner needs a proactive role in the feedback process, rather than simply being the recipient. In a review of varying feedback models, the authors cite multiple studies that have shown that feedback can backfire and be associated with no change or even negative change depending on the content, timing, and characteristics of the “deliverer.” The authors highlight new trends that suggest that feedback should be used as a strategy for enhancing a learner’s own self-evaluative and self-correcting practices.

When there is a misalignment between current and desired practice, accurately assessing can be challenging. Cognitive dissonance or expectation failure may be necessary to bring about a willingness to make deep conceptual shifts. One powerful method for creating opportunities for cognitive dissonance is through giving teachers the opportunity to view video recordings of their own practice. Teachers may believe they are fully implementing desired practices, when in fact, they have made little change in their instructional practice.

When there is a misalignment between current and desired practice, accurately assessing can be challenging. Cognitive dissonance or expectation failure may be necessary to bring about a willingness to make deep conceptual shifts. One powerful method for creating opportunities for cognitive dissonance is through giving teachers the opportunity to view video recordings of their own practice. Teachers may believe they are fully implementing desired practices, when in fact, they have made little change in their instructional practice.

Implications for Design: How might designers of professional learning support teachers as they shift to learner-centered practices?

Assess: Teachers self-assess current levels of performance in the desired practice area using a selected competency, pedagogical framework, or tool, and work with coaches and peers to reflect and solicit feedback as they identify current practices and habits.

Assess: Teachers self-assess current levels of performance in the desired practice area using a selected competency, pedagogical framework, or tool, and work with coaches and peers to reflect and solicit feedback as they identify current practices and habits.

Grow: Develop Targeted Skills

Once teachers have assessed their current practices and solicited feedback on a set of practices and habits they would like to shift, the next step is to engage in targeted skill building. When targeting specific learning outcomes for our young learners, you may have heard terms such as:

These same practices are effective with adults. Along with a framework or set of competencies to guide their growth, teachers need choice and autonomy in setting their own goals and choosing how they want to learn. They also need to engage in iterative cycles of learning with the support of a coach and/or learning community.

In addition to setting their own goals, teachers benefit from learning experiences that reflect their unique learner profile, including their readiness level, their learning needs and preferences, and their current problem of practice. A useful framework for customizing adult learning experiences to the needs of each learner is Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which centers each learner’s needs within various forms of representation, engagement, and expression.

In addition to setting their own goals, teachers benefit from learning experiences that reflect their unique learner profile, including their readiness level, their learning needs and preferences, and their current problem of practice. A useful framework for customizing adult learning experiences to the needs of each learner is Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which centers each learner’s needs within various forms of representation, engagement, and expression.

In Practice: Learning Couture in Iowa has adopted the UDL framework and asserts that the foundation of learner-centered pedagogy is using an equity lens to examine practices. In the process, they meet each learner where they are, paying careful attention to how they best access new learning and ideas, how they engage with learning experiences and other learners, and how they express what they know, understand, and can do.

Implications for Design: How might designers of professional learning incorporate learner-centered strategies with adult learners?

Grow: Teachers identify target skills and personal learning needs and preferences using learner profiles and learning plans, and then select and participate in new learning experiences that incorporate differentiated modalities.

Grow: Teachers identify target skills and personal learning needs and preferences using learner profiles and learning plans, and then select and participate in new learning experiences that incorporate differentiated modalities.

Experiment: Test and Affirm Through Iterative Cycles

After teachers select targeted skills and create a plan to engage in learning that matches their preferred method of accessing, engaging in, and expressing their learning, the next step is to try out these new skills with students.

Testing out new approaches is key to recognizing—and ultimately overcoming—ingrained misconceptions and replacing them with new beliefs. There are a number of ways that teaching professionals are already using this approach. For instance, a growing number of professional learning communities are using short-term inquiry, such as Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles employed as part of improvement science, to help shift teacher practice. The key is to keep these iterations job-embedded by ensuring significant portions of the learning are happening in context, not in theory.

Implications for Design: How might designers of professional learning help teachers learn by doing?

Experiment: Teachers engage with peers in a structured, iterative process (e.g., PDSA or Networked Improvement Communities [NIC]) to systematically apply (in context, not in theory!), observe, and plan refinements to improve practices over time.

Experiment: Teachers engage with peers in a structured, iterative process (e.g., PDSA or Networked Improvement Communities [NIC]) to systematically apply (in context, not in theory!), observe, and plan refinements to improve practices over time.

Sustain: Make Habits Visible and Reinforce Desired Shifts

Finally, if we aim to help teachers adopt and enact new equitable, learner-centered practices, we are going to have to help teachers recognize and address their ingrained habits of teaching that might be inconsistent with an equitable, learner-centered approach.

Research indicates that simply declaring a commitment to a new goal is insufficient for bringing about change in established habits. In fact, it is the strength of an existing habit—rather than the strength of an explicit goal—which is most predictive of future behavior. Here are a few of the promising habit-changing strategies:

- Identify the “cues” that trigger the unwanted behaviors or response and make a plan to replace the habitual response with the new desired response. This strategy requires high levels of awareness as well as self-control, and so is least likely to be successful.

- Identify existing habits that already align with your new goals. Associating the “new goal” with the “old habit” can help reinforce the desired behavior. In other words, find aspects of teachers’ practice that already align, and “rebrand” these as reflective of an equitable, learner-centered approach.

- Remove the situational triggers or cues that prompt the undesired behavior in the first place. For teachers, this might mean changing classroom routines, seating arrangements, or schedules to prevent undesired habitual responses from occurring.

Implications for Design: How might designers of professional learning support shifts in habits, rather than just shifts in aspirations?

Sustain: With partners, teachers reflect on enacted practices to identify desired and unwanted habits, engage in strategies to explicitly target and shift unwanted habits, and integrate new practices and desired habits into ongoing practice.

Sustain: With partners, teachers reflect on enacted practices to identify desired and unwanted habits, engage in strategies to explicitly target and shift unwanted habits, and integrate new practices and desired habits into ongoing practice.

Empowering teachers as drivers of their professional learning has never been more possible than it is today. By leveraging existing collaborative structures such as professional learning communities (PLCs) or other collaborative teacher teams, making time to assess, grow, experiment, and sustain new practices can quickly become part of how we do business as professionals.

Ready to Get Started?

To design professional learning with these principles in mind, click on the button below to access examples, resources, and practices used by one school to build new moves and habits to help drive change.

Learn More

Check out the other Making the Shift blogs and professional learning exercises designed to address the hidden drivers of teaching practice that can thwart change efforts!

- Making the Shift: Why Is It So Hard to Scale Equitable, Learner-Centered Education?

- Caution: Change Ahead! How Harnessing Emotions and Motivations can Help Drive Change for Equitable, Learner-Centered Education

- Sabotage! How Our Implicit Biases and Mental Models Keep Us From “Walking the Talk”

- Professional Learning Exercises for Teachers Making the Shift to Equitable, Learner-Centered Education

Dig deeper into the theory and research underlying an equitable, learner-centered approach in the Making the Shift report.

Andrea Stewart has worked for 11 years in personalized, competency-based learning and 24 years in education. She leads transformational change with schools, districts, education service/state agencies, institutions of higher education, and via national conferences and cross-state partnerships/consultation. She is the product owner and developer for the Customizing Learning Platform, and is the founder and CEO of Learning Couture, LLC.

Andrea served on the Iowa Department of Education’s CBE Task Force, CBE Collaborative, and Design Team where she led the state’s competency design and assessment process. Andrea also served on the Midwest Comprehensive Center’s Cross-state CBE Consortium, where she co-created micro-credential quality criteria/tools. She contributed to multiple technical advisory groups for the Aurora Institute’s National 2017 Summit on K-12 Competency-Based Education. Her work in CBE began in 2011, when she led pilot implementation of standards-based assessment and reporting and CBE in an Iowa district. Prior to this work, Andrea taught high school English for 12 years. She holds a BA in English Education from the University of Iowa, an MA in Teacher Leadership from Morningside College, and an EdS in Education Leadership from Drake University.