Education Philosophy Becomes Practice

CompetencyWorks Blog

This post was originally published at the Partially Examined Life: A Philosophy Podcast and Blog.

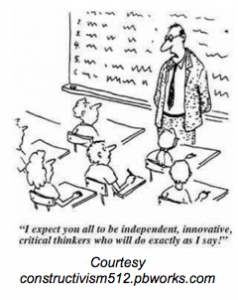

Over the past hundred years Constructivists and Traditionalists have enjoyed an uneasy truce in the world of education practitioners. Constructivism “says that people construct their own understanding and knowledge of the world, through experiencing things and reflecting on those experiences.” [thirteen.org] Traditionalists were more influenced by the “scientific management” of Taylorism, seeing schools on the industry model. Schools are factories with inputs, throughputs and outputs. The compromise between the two: educators would agree that Constructivism was true, but would act as if it were not.

Yes, it made sense as a model to discuss how learners “construct” knowledge” rather than “acquire” it. Of course, any teacher would say, students learn at different rates, in different ways, and according to their circumstance. But it was so impractical – hordes of students operating according to their individual motivations. Who can afford that? And how are you going to track progress? How will you know if you are getting your money’s worth from your schools?

Since John Dewey’s Democracy and Education educators have worked to bring Constructivist ideas into the classroom. Rockford College philosopher Stephen Hicks explains in this video the core of pragmatist education, which evolved into Constructivism.

The dominant Traditionalist paradigm treats schools like factories which should strive for efficiency and be able to match costs to outputs in a way that would please taxpayers and school boards. “And, by the way,” said the traditionalists, “most tax payers and school boards are traditionalist.” Yes, there were progressive, Constructivist experiments but the results of these experiments were inconclusive. Traditionalists argued that this proved that Constructivism was valueless. Constructivists argued that a few pockets of progressive practice couldn’t possibly survive or thrive within a traditionalist system.

But what if the practice spread through the system? What if, instead of operating in spite of the system, constructivist practice was supported and encouraged by the system? That may be happening.

Constructivists are rising. The argument for a constructivist approach to education has become ubiquitous and compelling, and the ethical dudgeon has been raised high. Last month in San Diego, representatives of the Education Departments of eleven states gathered as members of the Innovation Lab Network in order to plan their state’s move toward constructivism in the form of competency-based/learner-centered education. This is a direct challenge to the national education regime and its No Child Left Behind tendencies.

At the opening, the conferees accepted key constructivist ideas as given:

1) Learning occurs best when the student is self-directed and engaged,

2) Context and motivation are profound influences on a student’s potential learning,

3) Knowledge is socially constructed, and no teacher could possibly “know” what their student knows – especially not through pencil and paper tests,

4) Teachers act as coaches or facilitators of learning, rather than as experts “filling empty vessels,”

5) Curriculum, instruction, and assessment can all be designed and executed in a way that takes all of these truths into account and allow authentic learning to occur.

6) Most importantly, because of advances in technology – laptops, iPads, etc. – enacting a constructivist vision is not only possible, it’s practical.

Education consultant Robert Marzano has been promoting this vision through research and advocacy for over a decade, as have Linda Darling-Hammond and others. Bea McGarvey and Chuck Schwahn, in their slim but influential book, Inevitable: Mass Customized Learning in the Age of Empowerment (2012), amplify the idea that the pragmatic, constructivist vision of education is now possible. (And by “possible” they mean, “affordable.”) The key, according to McGarvey and Schwahn – whose book leans very heavily towards advocacy and practice, rather than philosophy – is that technology has increased profoundly a school’s ability to manage the massive amounts of information produced in a truly constructivist classroom, with each learner having their own learning plans, their own measures, and their own schedules. Here is a video with McGarvey.

Being able to monitor this amount of data to track students assuages the great fear of constructivist education – i.e., that the classroom will devolve into a Rousseauian state of nature . It allows the student to plan their own paths and find their own resources. It allows the teacher to respond to student needs individually, rather than in crowds. And it allows the district to document learner growth for purposes of accountability to the state, federal government, and taxpayers. (It also, by the way, gives the learner access to more resources than one could possibly have imagined, even ten years ago.)

Thus, because technology has eased the logistical condition of education, we see a shift in the philosophical condition of education. We see constructivist philosophy gaining in “cash value.” In Maine, for example, 50% of all school districts have committed to shifting towards proficiency-based/learner-centered education, and the legislature passed a law a requirement for proficiency-based diplomas. Kentucky, Wisconsin, and Oregon are taking similar steps. It’s no longer a subversive philosophy used to push back against an over-bearing, bureaucratic system. Rather it is coming to define the system.

Gary Chapin is a Senior Associate at the Center for Collaborative Education.