Collecting a “Body of Evidence”

CompetencyWorks Blog

This is the second in a series of articles specific to the developing understanding of skills and dispositions of educators working with students in a competency-based educational system. There has been increased recognition nationally of the importance of skills and dispositions and how these are entwined within the overall growth and College and Career Readiness of learners. The skills and dispositions are referred to in a number of ways (Non-cognitive skills, Habits of Learners, Work Habits, General Learning Outcomes, “soft skills,” etc.). Our school has been delving into skills and dispositions for the past few years, but we have found that there are limited resources to support our work, and at times, this has caused frustration. We are very excited about the opportunity to work with the recently released Essential Skills and Dispositions Frameworks (Lench, S., Fukuda, E., & Anderson, R. (2015)) this upcoming school year to support our continued learning in this area. For the purposes of this series of articles, we will be using the term the State of New Hampshire recognizes, Work Study Practices. Locally, we have aligned the Responsive Classroom’s CARES to our State of New Hampshire’s Work Study Practices, which are referenced in this series of articles.

This is the second in a series of articles specific to the developing understanding of skills and dispositions of educators working with students in a competency-based educational system. There has been increased recognition nationally of the importance of skills and dispositions and how these are entwined within the overall growth and College and Career Readiness of learners. The skills and dispositions are referred to in a number of ways (Non-cognitive skills, Habits of Learners, Work Habits, General Learning Outcomes, “soft skills,” etc.). Our school has been delving into skills and dispositions for the past few years, but we have found that there are limited resources to support our work, and at times, this has caused frustration. We are very excited about the opportunity to work with the recently released Essential Skills and Dispositions Frameworks (Lench, S., Fukuda, E., & Anderson, R. (2015)) this upcoming school year to support our continued learning in this area. For the purposes of this series of articles, we will be using the term the State of New Hampshire recognizes, Work Study Practices. Locally, we have aligned the Responsive Classroom’s CARES to our State of New Hampshire’s Work Study Practices, which are referenced in this series of articles.

The first article in this series, Our School’s Developing Understanding of Skills and Dispositions, may be found here.

During our school’s transition to a competency-based educational system, our understanding of the importance of Work Study Practices has evolved significantly. One of the major shifts in our understanding has been relative to the importance of building a body of evidence specific to a child’s demonstration of Work Study Practices. During the initial stages of this transition, teachers may have only put one grade per marking period related to skills and dispositions. This began to change as teachers began to question why we wouldn’t be assessing work study practices on a more formative, ongoing basis as we did with our academic competencies. The resulting grade would be far less subjective than a “one-time” assessment at the end of the marking period.

Teachers also began to question how the resulting information was reported. Traditionally, it had not mattered that there was only one grade in a system because that was all that would be reported anyway. But now, with a body of evidence for each child, the information was averaging. We knew from our experience that this wasn’t a fair or accurate indicator of reporting either. We had moved away from “averaging” as part of our transition to a competency-based system. We knew that the most recent, consistent data was most relevant. It gave us information on where a student was on that DAY, not a compilation of the data over the course of six, ten, or even twelve weeks. This resulted in our district turning on the “trend-line” to report Work Study Practices, as we were doing for our academic competencies.

Building a body of evidence for our students’ CARES (Work Study Practices) has allowed us to truly follow a child’s growth, help them progress in specific areas, and provide the child and his/her parents with relevant and timely information related to where he/she currently is in his/her progression.

The insight of two of our teachers below describes their growth in understanding as we began the shift to a competency-based educational system. Their reflections within this particular article are specific to their developing understanding of the importance of Work Study Practices within their classrooms, and how the assessment of Work Study Practices is no longer considered just once at the end of a marking period. This change in mindset has proven to have an impact on not only how we assess WSP, but how integral it is to the learning process itself.

Jill Lizier, Grade 1 Teacher

Monitoring CARES has become a natural way for teachers to keep track of a student’s work study habits. These work study habits are what allow my first graders to become successful members of a classroom community as well as self-directed and confident learners. This is a process that involves modeling, discussion, and monitoring by the teacher. As students become more familiar with CARES, they can even begin to monitor themselves!

My grade book has become a way to keep track of assessing how students are progressing in the CARES attributes. When I first started to monitor CARES, I would put one grade for each cares attribute at the end of each trimester. I used to think to myself, “Okay, where is this student right now in the area of Cooperation? Well, he did well yesterday during a game, so he must be meeting expectations!”

This way of grading CARES was no different than the check plus and check minus we used to do. It was just a one-time grade that did not account for growth. I realized if I made CARES a part of every lesson and activity then I would be able to put in multiple grades for CARES attributes, allowing me to monitor CARES growth over time.

The teacher’s grade book becomes a body of evidence of the student’s growth through the year in CARES. It is helpful as a teacher to have this ongoing monitoring, since some days I look back and can’t remember what I did the day before! With this evidence, teachers can discuss progress with parents, but more importantly, with their students. I am able to look back into my grade book and see that the past few times I have monitored cooperation, a particular student still wasn’t able to cooperate without teacher assistance. I am now more aware that I need to incorporate more cooperation discussions with the class. But, I can also help an individual child understand that he or she may do really well in one area of CARES but needs to focus on another.

Monitoring student growth in the area of CARES is not only good for social growth but academic growth as well. It is my hope as a teacher for these CARES attributes to become common vocabulary within the classroom and for students to make connections by recognizing their importance outside of the classroom and in the world around them.

Terry Bolduc, Grade 5 Teacher

As a school, we were focusing on the importance of collecting a body of evidence that represents each student with regards to academic standards and competencies. I realized that it was important to do this for Work Study Practices as well.

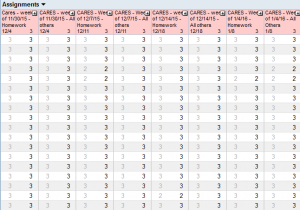

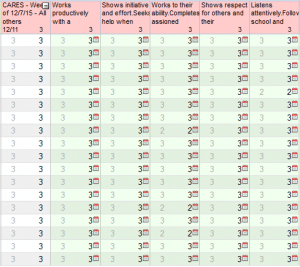

Initially, I began entering a weekly CARES grade for my students, rather than what was historically done which was one grade, written on the report card at the end of the trimester. As this weekly grade became routine for me, I began to look more closely at each component that made up each CARES category. I realized that these grades needed to be broken out further so I could really keep track of the areas that were deemed important to a student’s success. For example, under “R” for responsibility, the following components are listed: Works to the best of their ability, completes assigned tasks, and completes assigned homework. If I entered one weekly grade for this WSP category, was I truly reflecting on how the student was performing? How would I remember if they were proficient in completing assigned tasks but maybe not so good at turning in homework? It was then that I started further separating out WSP grades even further. I believe, only then, that my grade book was reflecting a true picture of each student and their achievements both academically and socially.

The two pictures below are directly from Ms. Bolduc’s grade book. The first picture represents the overall CARES in the grade book, week by week.

The second picture represents the assessment data broken down within one of the weeks, by assignment.

For more information on Terry’s changing practices related to WSP, please click here.

See also:

- Our School’s Developing Understanding of Skills and Dispositions

- Addressing Root Causes at Memorial Elementary School

- Tying It Together with Performance Assessments

Jonathan Vander Els is the principal of Memorial School in Newton, NH. Jonathan has presented at multiple local, state and national conferences on topics related to competency-based grading, enhancing teacher leaders in schools, maximizing collaboration of staff through highly functioning Professional Learning Communities, and providing tiered instruction for learners of varying abilities. Jonathan may be followed on Twitter: @jvanderels

Jill Lizier is a first grade teacher at Memorial School in Newton, NH. Jill is an active contributor to Professional Learning Communities within the Sanborn Regional School District. Jill has worked as team leader for her grade level and is currently a Quality Performance Assessment trainer within Memorial School. Jill may be followed on Twitter: @jilllizier

Terry Bolduc is a fifth grade teacher at Memorial School, in Newton NH. Terry has worked as a team leader for her grade level, participates in the PACE initiative as a grade level representative for the Sanborn Regional School District, has been member of the school’s Training Team and is currently a Quality Performance Assessment coach within Memorial School. Terry may be followed on Twitter: @tabolduc