A Timeline of K-12 Competency-Based Education Across New England States

Education Domain Blog

This post first appeared on CompetencyWorks on January 10, 2017.

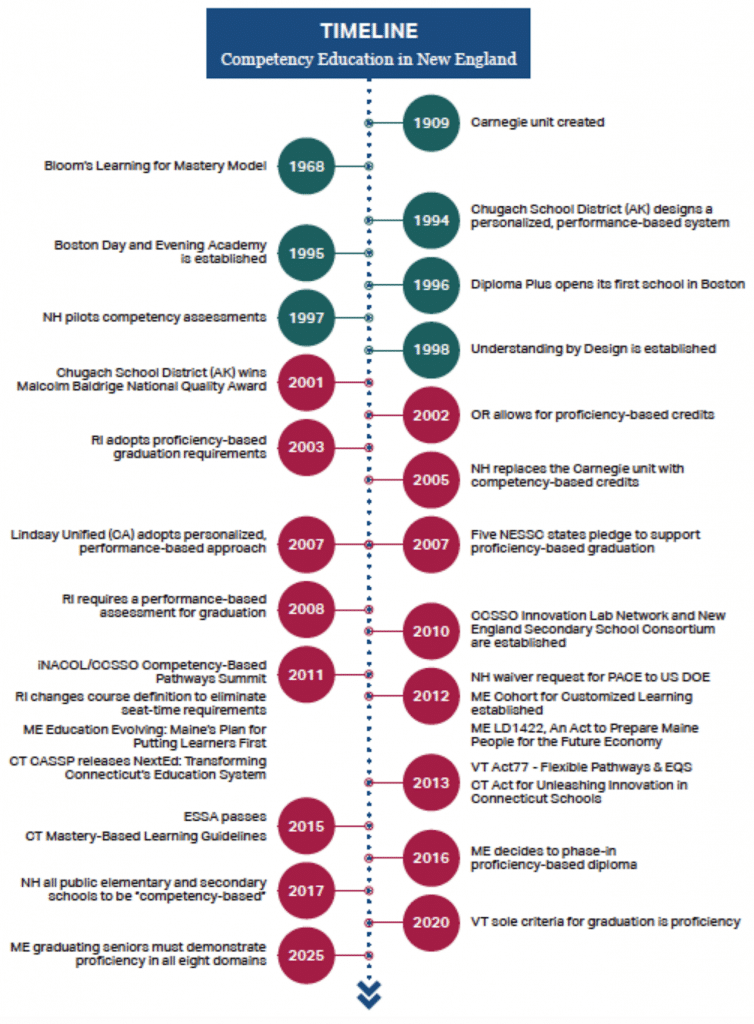

The New England region stands out for its early innovations, bold vision, and high percentage of districts becoming competency-based. Yet, a quick glance at the timeline shows that the earliest models popped up on both sides of the country – in Boston and Anchorage – around 1995. So why is it that competency-based education has taken hold in New England with such momentum?

Let’s take a look at a few of the possibilities.

A Good Idea Creates Continuity

The New England states have not had continuity in leadership. Governors have changed, as have the Secretaries of Education and other key personnel. Complicated budget issues, volatile political dynamics, and redistricting have demanded attention. Yet competency education has continued to be a major priority. Why? Because there are enough people in influential positions who believe in it. Some have argued that because students in New England states are relatively high-achieving, there just isn’t any other way to generate improvement except to create a more personalized, flexible system. Moreover, many educators will vouch for it, affirming that once you understand what competency education can do, there is no going back. With strong local control, this makes it harder for state leadership to change course because the policy is perceived as beneficial to students and educators.

Geographic Size

The small geographic size of New England states helps, but can’t fully explain the momentum. Small states can make it easier to bring people together to build a cohesive vision and understanding of competency education. Small districts can also be an advantage in creating a dialogue within schools and with communities about why the change is important as well as managing mid-course corrections in implementation. Yet, every state big or small faces the same challenges of scaling beyond the coalition of the willing.

A Catalytic Intermediary

Great Schools Partnership (GSP) has played a vital role in advancing proficiency-based learning. It has provided technical guidance to states in their efforts to create policies, helped to develop exemplars of graduation expectations, convened admissions offices in higher education to eliminate any potential barriers of proficiency-based diplomas, and provided training and technical assistance to districts and schools. They have demonstrated enormous generosity in sharing their resources under Creative Commons licensing. As an intermediary, GSP has also developed expertise across states, thus building extraordinary capacity in understanding the choices and implications of different policy and design decisions.

History of Inter- and Intra- State Collaboration

The New England states have a history of collaboration across states and within states. For example, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont have used the same standards and same state assessment system, the New England Common Assessment Program.10 All of the New England states, with the exception of Massachusetts, formed the New England Secondary Schools Consortium (NESSC) and its regional professional learning community, the League of Innovative Schools (LIS), which has spurred on the efforts to introduce personalized, competency-based education. In 2007, the commissioners of five states signed a pledge to implement proficiency-based graduation, flexible learning pathways, and redesigned student-centered accountability systems. This common commitment has meant that the states are advancing together, with no state too far behind or too far ahead. NESSC and LIS have also generated and disseminated effective practices across the networks so that districts and schools receive support even when state resources are not available.

Strong Philanthropic Partners

There is no doubt that philanthropy has played a catalytic role in advancing competency education in New England. The Nellie Mae Education Foundation has played a powerful role through the combination of strategic investments throughout New England to support student-centered learning and the inspirational leadership of one of the early leaders of competency education, Nicholas Donohue, the Commissioner of Education at the time that New Hampshire redefined the Carnegie unit credit and now the foundation’s President. With the addition of another regional foundation, the Boston-based Barr Foundation, with a team of program officers knowledgeable in personalized learning and competency education, it is likely that these foundations will have even greater catalytic influence.

Leadership

Leadership matters. We know it does. There has been extraordinary leadership in the New England states at the school, district, and state levels – too many to list here. There are leaders willing to convert to competency education before the idea takes hold because they feel it’s the right thing to do for students. There are leaders who have created the early models and provided opportunity for others to see it in action. There are leaders who excel in engaging others in sharing a vision and the belief that it is possible to transform the education system. There are policy leaders working together to support each other across states. There are leaders who possess an imagination big enough to begin to put into place the new systems based on transparency, empowerment, and responsiveness that will help students succeed no matter what their backgrounds.

There are two qualities of leadership that abound in the state policymakers, districts, and schools leading the way in New England. First, they are leader-learners, always seeking to better understand, to become more effective, and to seek out the best ideas even if it means accepting that theirs might not be. Second, many district and school leaders possess the participatory leadership styles (referred to as distributed, adaptive, or transformational leadership) needed to help educators move from the traditional system to embrace the values and create the conditions for a more personalized, competency-based system. Are these qualities we can only find in New England, with its history of town meetings? Doubtful. They can be found all across our nation. However, it is possible that the multiple networks and collaboratives in New England have helped to nurture and popularize these forms of leadership.

What does this all mean for other states that are geographically larger, operate in isolation, or lack catalytic intermediaries and foundations? It means they will need to figure out their own strategic advantages, develop partnerships, and, if necessary, seek to form partnerships outside their region to tap into the expertise they need. They, too, will need to create cultures of learning, engage communities in defining what they want for their children, and develop their own shared vision and values to ignite the transformation process. Other states without these same advantages are making big leaps toward competency education. For example, Colorado has developed a strong supportive approach, with districts working in cohorts to learn about and develop strategies to advance competency, while Idaho is building knowledge and networks through nineteen district pilots of competency education.

To learn more about advancing K-12 competency education in New England states, download the latest report and follow us on Twitter (@CompetencyWorks).

Follow this Blog Series:

Post #1 – Five Drivers of Transformation in New England States

Post #2 – The Trouble with Prescriptive Policies When Paradigms are Shifting