RSU2: Entering a New Stage in Building a High-Quality Proficiency-Based District

Education Domain Blog

This post first appeared on CompetencyWorks on January 5, 2016, and it is part of the Maine Road Trip series by Chris Sturgis. This is the first post on her conversations at RSU2 in Maine.

RSU2 is a district that has been staying the course, even  through two superintendent changes (Don Siviski is now at Center for Center for Secondary School Redesign; Virgel Hammonds is now at KnowledgeWorks; and Bill Zima, previously the principal at Mt. Ararat Middle School, is now the superintendent). This says a lot about the school board’s commitment to having each and every student be prepared for college and careers. If we had a CompetencyWorks award for school board leadership, RSU2 would definitely get one.

through two superintendent changes (Don Siviski is now at Center for Center for Secondary School Redesign; Virgel Hammonds is now at KnowledgeWorks; and Bill Zima, previously the principal at Mt. Ararat Middle School, is now the superintendent). This says a lot about the school board’s commitment to having each and every student be prepared for college and careers. If we had a CompetencyWorks award for school board leadership, RSU2 would definitely get one.

Given that they are one of the districts with the most experience with competency education (Chugach has the most experience, followed by Lindsay), my visit to RSU2 was much more focused on conversations with the district leadership team, principals, and teachers rather than classroom visits. My objective in visiting RSU2 was to reflect with them upon their lessons learned.

It takes a load of leadership and extra effort to transform a traditional district to personalized, proficiency-based learning. It’s a steep learning curve to tackle – growth mindset, learning to design and manage personalized classrooms, learning how to enable and support students as they build habits of work and agency, designing and aligning instruction and assessment around measurable objectives and learning targets, calibration and assessment literacy, organizing schedules so teachers have time for working together and to provide just-in-time support to students, building up instructional skills, new grading policies, new information management systems to track progress – and districts have to help every teacher make the transition. I wanted to find out what they might have done differently, what has been particularly challenging, and what they see as their next steps.

I began my day at RSU2 in Maine with a conversation with Zima (a frequent contributor to CompetencyWorks); principals from all nine schools; Matt Shea, Coordinator of Student Achievement; and John Armentrout, Director of Information Technology. I opened the conversation with the question, “What do you know now that you wished you knew when you started?”

Tips for Implementation

Armentrout summarized a number of insights about implementation:

- Start with the why. The school community needs to understand why the traditional system isn’t working well and why proficiency-based education is better for students. Be prepared to return to the “why” for parents who move to your community, to continue to engage community leaders, and to build the will when you need to change any far-reaching traditional practices.

- Be clear about what is important. Carefully select the core concepts that will drive all your decisions and make sure “you pick the hills you are willing to die on.” There are so many things to change, but you don’t need to do it all at once. You’ll want to have the voice of different stakeholders involved so you don’t pick concepts they’re not willing to give up.

- Put on “what’s best for kids” lenses. Develop different lenses that can be used to identify what is best for kids. There isn’t just one lens. You might need to think about how students learn, what is developmentally appropriate, or implications for sub-groups. If you use those lenses, you can tell when something is adult baggage. If you use a what’s best for kids lens, you can solve any problem.

Accelerated Implementation Timeline

Steve Lavoie, Principal at Richmond Middle/High School, explained, “Rolling out year by year ended up dragging out the implementation process. We started with ninth grade and we would convert to proficiency-based practices as the students entered the next year. It would have been much better to just jump in and implement across the entire school. By doing a year-by-year roll out, we sent a signal that we were piloting, which was interpreted by some to mean we were not committed.” (For more on Lavoie’s insights, see Phase in or Overnight Your Implementation, Preparing to Turn the Switch to a Proficiency-Based Learning System, andMiles and Benchmarks on the Way to a Proficiency-Based System.)

have been much better to just jump in and implement across the entire school. By doing a year-by-year roll out, we sent a signal that we were piloting, which was interpreted by some to mean we were not committed.” (For more on Lavoie’s insights, see Phase in or Overnight Your Implementation, Preparing to Turn the Switch to a Proficiency-Based Learning System, andMiles and Benchmarks on the Way to a Proficiency-Based System.)

An example of the problem that developed in a year-by-year roll-up starting in ninth grade was that the school was managing two grading systems. Lavoie explained, “It was a really bad idea to have two types of grading systems within a school. In the first few years we had ninth and tenth grade teachers doing 1-4 scoring based on learning and the older grades using traditional 100 point score. Never set up a situation where you have to do grade conversions as it undermines the culture of learning. However, it is a necessary evil to have to do conversions for GPA.”

Teach Students at Their Academic Level, Not Grade Level

RSU2 leaders described that converting to measurement topics and learning targets has been very effective in helping students who have the prerequisite knowledge to learn the skills. However, in hindsight it would have been wiser to build the capacity to use the system of topics and targets to support students where they were in their own learning progression. Lavoie explained, “Ideally we would have shifted our perspectives to look at the continuum of learning rather than continue to have measurable learning objectives structured within grade bands. We need to know where are the kids on our continuum of learning.”

Armentrout added, “There are many implications to consider in how a school creates the architecture of the measurement topics and learning targets. One of the things to think about is how it will support students who do not have the foundational knowledge for the age-based curriculum.” Lavoie noted, “Everyone has some holes in their learning, even the valedictorian, but when students do not have prerequisite skills or have significant gaps in their learning, it creates tremendous pressure on the teachers and the students.” (More on this in another post.)

Build the Structure and Skills for Students to be Self-Directed Learners and Teachers to be able to Personalize Learning

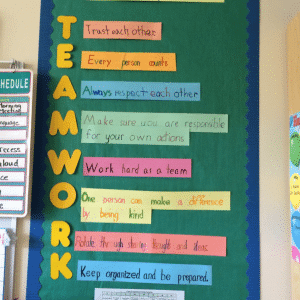

During our conversation with the principals, several mentioned that they had learned a lot more about how to structure the classroom and the school to help students become self-directed learners. They launched their efforts with training for teachers on how to design personalized classrooms, including how to have students build a sense of ownership of the classroom culture through building a shared vision and code of cooperation. This is a practice that can be used with the littlest ones all the way through high school.

By using standard operating procedures, teachers are able to create more learner-centered classrooms. When students are able to manage themselves, teachers can focus more on instruction and working with students. Matt Shea pointed out, “We’ve learned that it is important to focus on helping students to learn skills. Without the skills or habits of work, students are self-paced. With the skills, they become self-directed learners.”

Figure Out Level 4

Everyone laughed a bit when the issue of Level 4 was raised – laughing with a bit of discomfort, as it is still a tough issue to figure out how to operationalize at RSU2 (and every other school I’ve visited). Armentrout suggested, “It is worth having early conversations about what you mean by Level 4 and when students will be able to achieve it. Otherwise you risk it becoming extra credit.”

At RSU2, the scoring is aligned with the first four levels of knowledge based on the Marzano taxonomy: retrieval, comprehension, analysis, and knowledge utilization. There is a target level, indicated as Level 3, which is set at the appropriate level based on the standard. There is also a foundation level that is usually set at retrieval and comprehension.

There are several things to consider about Level 4. Armentrout explained, “If you don’t figure this out, then the only way for students to excel is to go faster, and it is easy for students to think that faster is better than slower. We found that some students wouldn’t risk striving for a 4 because it would take time and they might fall behind.” Some teachers try to build assessments that have questions aimed at different levels so students have the option of answering more challenging questions. Another aspect of the Level 4 question is based on the granularity of standards. In most cases, students aren’t going to be demonstrating knowledge utilization (applying standards within a new context) for every standard. Applying academic skills is going to generally mean using multiple standards in some type of a project.

RSU2 is now thinking about other ways to ensure students have the opportunity to apply their knowledge and achieve Level 4. Stay tuned.

How to Support Teachers Through the Transition

An elementary school principal noted, “The biggest surprise for our teachers was that students learned much faster than expected. You couldn’t just be one page ahead of them anymore. You had to have your units organized for today and for tomorrow.”

Two points were made regarding the structure of the proficiency-based system. It is important to make sure that teachers understand the alignment between the way the measurement topic is written, the instruction, and the assessment. A principal noted, “If you want students to be able to analyze something, then you need to make sure the activities and the assessment are aligned.” Another principal emphasized that it is important to stay focused on the student with, “Sometimes we overthink. We create too many layers of a system. The key is to stay focused on what this individual student needs to move forward and have the flexibility to be able to get the resources to them. Always ask the question, ‘What does this student need and how are we going to help them?’”

FYI: Courtney Belolan, a frequent contributor to CompetencyWorks and has joined the team at RSU2 as a coach. You can find her learner-centered tip of the week at CompetencyWorks on Fridays.

Being a Principal in a Proficiency-Based System

Everyone had something to say about how their jobs had changed working in a proficiency-based system.

- We have much richer conversations, often much more philosophical. We work together to clarify our overall theories about pedagogy and how to engage students.

- Previously, our worries were about scheduling and administration. Now we have a stronger focus on people. We use staff meetings to talk about issues important to professional development. We don’t let nitty gritty administrative details take up time in meetings.

- One of my new responsibilities is to support team time for teachers. I need to make sure they have time to meet together to plan and to work in PLCs.

- I now take time to learn about how other schools are doing things. I’ve been learning about the personal learning plans that are being used in Vermont.

- My hiring practices have changed. I want to find staff that will embrace our philosophy for all the jobs in the schools. I want teachers who want to collaborate.

- I spend more time staying on top of how teachers are doing. I want to make sure I am supporting struggling teachers. Sometimes it takes time to help teachers understand how they can improve their instruction. They have been so used to working in isolation, and I often have to remind them that they can’t do it alone.

- I say “I don’t know…yet” a lot more than I used to.

Susan Lobel, Principal at Hall-Dale Elementary explained, “We can’t underestimate what shifting to a proficiency-based system means for teachers. It’s a profound change for teachers to work with learning targets and assessing them.” Teachers, even experienced teachers, find that they have gaps in their own skills or that they may have been designing instruction and assessment at lower levels. Principals’ skills as instructional coaches are going to become even more important in guiding teachers to build their skills.

Lobel continued, “You have to be prepared to support teachers as their sense of responsibility increases. When we shifted from ‘I taught it’ to ‘Have they learned it?’ teachers began to feel so responsible. They care so deeply and when students aren’t making progress, their own confidence is shaken.” Zima emphasized this point with, “Learning can be frustrating, especially if you don’t get it right the first time. Just as our students have to learn to manage the emotions that spring up throughout the learning process, so do our teachers. We all need to prepare ourselves to manage the frustration that erupts from time to time.”

Continued Improvement at RSU2

The leadership team at RSU2 is constantly trying to figure out how they can strengthen and improve their personalized, proficiency-based system. Much of their focus is currently on improving instruction. RSU2 is using the Art and Science of Teaching as a field guide or reference. They are strengthening their Professional Learning Groups (their term for PLCs) to further develop meaningful domain questions that can engage students. Principals are using iObservation to gather data and provide resources for helping teachers build their instructional skills. While I was there, Bea McGarvey, co-author of Inevitable: Mass Customized Learning, was working with teachers to help them think through more deeply how they can more effectively personalize the instructional cycle. She is also going to be supporting RSU2 teachers in building their skill in using formative assessment and improving standards-based grading practices.

The team at RSU2 is also thinking more deeply about how to provide opportunities for students to “stretch themselves toward going deeper in their learning.” Zima explained, “We are still expecting students to memorize facts even if they are at our fingertips. It is an entirely different experience when it is inquiry-based. Facts are sucked into the vortex of a kid who is engaged by a big question. They gain meaning because they can be used, not just memorized.”

They are also beginning to sketch out different models about how to organize the day. For example, one idea for middle school is to organize around fundamental skills and “exploratories.” Part of the day, students would focus on building language arts and math skills, and the rest of the day would be organized around inquiry-based, project-based, and expeditionary-based learning within the context of sciences and social sciences. Students could build and apply skills within big, engaging questions. (Check out this video explaining their ideas about applied learning to help students toward deeper learning.)

RSU 2 is also interested in making sure that students write every day. Some may not think of this as deeper learning, but in fact, when students build their skills to express themselves, they also build the skills to analyze and communicate more complex dynamics.

As I listened to the team at RSU2 explore these ideas, I started wondering – is beginning to redesign the school day the next step for districts that have been able to build the foundation of personalized learning?

—

It was a great experience to spend a day with this group of incredible educators who have been deep into proficiency-based learning for five years (see case study on their launch). Thank you to everyone for being so generous with your knowledge.

See also: